eorge Pinwell is usually classified, in the words of Forrest Reid, as an 'Idyllic' (vii) artist of the Sixties. His work is characteristically concerned with rural themes and is equally divided between representations of the 'country' middle-class and their workers. His most typical work is found in the illustrated gift books of the 1860s.

On the face of it, Pinwell is the perfect artist for what is ostensibly an extremely anodyne form. His lyrical scenes of middle-class ladies in huge crinolines, idealized natural detail and quaint rural architecture are (apparently) the very embodiment of the undemanding subject matter that was favoured by consumers of this type of publication. Gift books were never intended to challenge, and Pinwell offers a version of the rural idyll that soothed the senses and helped to construct a notion of Englishness, of England-the-timeless-idyll, that still has currency today. Embodied most notably in Wayside Posies (1867), Pinwell's art is a mid-Victorian version of an older romanticism, a domesticating of the countryside that is rendered with academic exactitude.

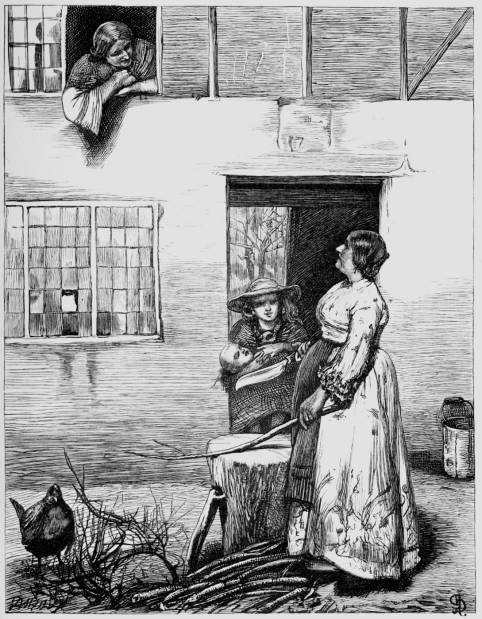

Four illustrations by Pinwell (from left to right): (a) The Shadow. (b) By the Dove-cot. (c) The Island Bee. (d) At the Threshold. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

However, it would be unwise to view his art in the same terms as the bland Birket Foster. On closer inspection, we can see that Pinwell's poetic approach is often a complicated mixture of surface lyricism and psychological drama, idealism and journalism, celebration and criticism. This series of tensions is apparent in even his most straightforward representations of the bourgeois idyll, but it takes a sharper form in his representations of the workers.

These characters are never shown in idealized terms, but as a morose people who rarely interact and whose gaze is invariably turned inwards. In the words of Paul Goldman, 'Pinwell's hooded and introverted creations rarely look out directly at the viewer. . . . It is the use of such devices that gives so many of his compositions a sense of remoteness...which can be memorable' (119). Pinwell may show rural folk, but he could barely be said to present the sort of bogus idealism that was favoured by a middle-class audience. He also refuses to show idealized physical types, instead showing his peasants as unhealthily fleshly, or pallid and ill-fed. Pinwell could not really be described as a social realist in the modern sense of the term, but there is no doubt that he prefigures the more journalistic approach of Herkomer and The Graphic artists of the 1870s.

Bibliography

Houfe, Simon. The Dictionary of Nineteenth Century British Book Illustrators. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club, 1978; revised ed., 1996.

Goldman, Paul. Victorian Illustration: The Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians. Aldershot: Scolar, 1996.

Reid, Forrest. Illustrators of the Eighteen Sixties. 1928; reprint, New York: Dover, 1975.

Created 11 November 2009

Last modified 20 September 2024