[Click on thumbnails for larger images and additional information]

Dudley’s reputation: life and art

[Bill Burns writes “For some unknown reason, Dudley's date of death is incorrect on most art reference sites and is given as 1900. However, I have confirmation from the family that the year of his death was actually 1909; I also have a letter signed by Robert Dudley dated January 1909.” — George P. Landow]

Robert Charles Dudley (1826–1909) was a versatile artist who enjoyed a considerable reputation in his own time. A painter of seascapes, he practised across a range of printing media; mainly a lithographer and chromolithographer, he was also a draughtsman drawing on wood for mid-Victorian periodicals; an accomplished designer of book-covers (Ball, p.148; King, p.16) and Christmas cards (1887); and a writer and illustrator who published a number of black and white and coloured books for children. Highly productive, he is most remembered for his vivid illustrations for The Atlantic Telegraph (1866), and for his bindings. Constrained, like all of his contemporaries, by the conditions of a crowded and competitive market, Dudley was willing to turn his hand to whatever employment was available.

However, he was never a wage-slave and his complex work-pattern, doing whatever was available and suitable, was in his case a slightly surprising development. Unlike many artists who came from lower middle-class backgrounds or ‘from trade’ – as in the case of E. H. Wehnert, whose father was a tailor – Dudley had the advantage of being born into the moneyed bourgeoisie, and did not have to work to live. His father, Charles Stokes Dudley, is recorded on his son’s marriage certificate as a London ‘gentleman’, and Robert would have enjoyed the benefits of a comfortable childhood, finally inheriting the family’s wealth. This situation is reflected in the fact that he lived for most of his adult life at one address, 31 Landsdowne Road in fashionable Notting Hill, owning a property which, while not in the same league as houses in Belgravia or Holland Park, was far beyond the means of most of his fellow-artists, and a marked contrast to the situation of contemporaries such as John Franklin and John Sliegh, who lived in rented accommodation as lodgers. He may also have benefitted from his marriage in 1859 to Amelia Hunt, the daughter of the successful Liverpool artist of domestic genre, Andrew Hunt. No doubt this union brought a significant dowry, and Dudley’s life, buttressed with old money, was essentially that of a prosperous ‘gentleman-artist’. Freed from the necessities of having to work, he nevertheless engaged with a wide range of projects, an approach that sustained his interest through a varied and prosperous life.

Following a false start which involved the exhibition of a genre piece at the Royal Academy in 1853 (an endeavour that erroneously led to the chronicling of two artists of the name of Dudley, even though they are the same person), his earliest work was essentially of technical rather than artistic value. His earliest training is unknown, but must have been in a lithographer’s workshop. In the early 1850s he held the post of principal draughtsman under the direction of the architect Matthew Digby Wyatt, in charge of the recording of the monuments in the Medieval and Renaissance Courts at the Sydenham Crystal Palace. This was followed by other journalistic work. Engaged by Day and Son, the chromolithographers who published luxurious picture books and were the leading practitioners in the field, Dudley became a specialist in the representation of applied art. The best of his early work appears in Examples of Decorative Art, Selected from the Royal and Other Collections [1860]. This is a detailed catalogue of a range of exotic and patterned objects; like all artists working in the milieu of the time, he was bound by the Pre-Raphaelite fascination with ‘facts’ and ‘truth’, and here, as elsewhere, he is primarily concerned with the ‘copying’ of ‘reality’. Though decorative in effect, these are essentially straightforward informational designs, and at this point Dudley seems very much a technician/artist, supplying a vast market with commemorative or functional images in bright and sometimes livid colours.

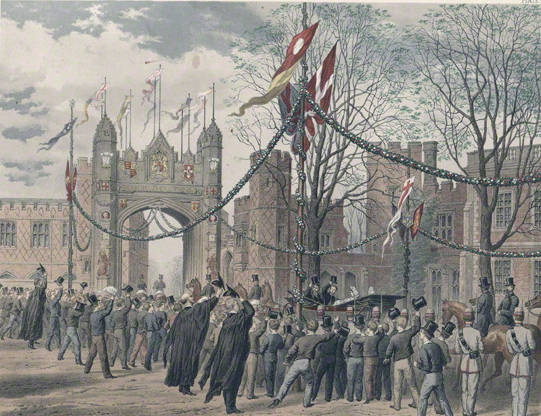

His art takes an imaginative (and slightly troubling) step forward in the form of a series of 41 chromolithographs for A Memorial of H.R.H. Albert Edward Prince of Wales and H.R.H. Princess of Denmark,also known, with rather greater brevity, as The Wedding at Windsor (1863 and 1864). This album is a montage of the events and characters. A celebration of the opulence and traditions of the British Royalty, it provides a detailed representation of interiors, landscapes, architecture and costumes. Produced, once again, by Day and Son, its subject-matter is well-suited to the saturated colours and precise lines that characterise the chromolithographic medium. Ruari Maclean considers these images ‘the highest point of faithful representation yet achieved by chromolithography’ (p.132); a perfect souvenir, they provided their curious middle-class audience with an insight into the rituals of the aristocracy. Heraldic in character, the Wedding seems both fantastic and realistic, a catalogue of super-charged artefacts which ultimately have the hallucinatory unreality of a dream, rather than the super-realism the artist was aiming at. His figures, especially, are more like observed things rather than individuals, porcelain models of people than people. This tendency is exemplified by his treatment of The Bridesmaids, which seem like some many ornaments on display

Left to right: (a) Eton School and the Boys' Arch. (b) The Bridesmaids. (c) The Dean's Cloister at Windsor [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Dudley’s work both here and throughout his drawing on stone is nevertheless of the highest quality, and by the mid-sixties he was recognised as one of the leading practitioners of the process, and one of the Days’ principal men. At this time he was also working as an artist in black and white, and seemed able to shift effortlessly from chromolithography to wood-engraving. He did illustrations for a version of the Bible (1860), embellishing its pages with severe designs ‘freely adapted and drawn on wood’, contributed to The Library Shakespeare [1873–75], and produced sundry images for a series of children’s books, several of which were engraved by the Dalziels.

Children’s books became a mainstay in the seventies, eighties and nineties, and Dudley was the author and illustrator of a series of successful publications. These included The Twigs [1890], a bizarre piece of anthropomorphism in the manner of Harrison Weir and Ernest Griset, and King Fo, the Lord of Misrule [1884], a book of medieval fooling in livid tones. He also supplemented his own endeavours with illustrative work for John Edgar’s The Boy Crusades(1865), Franz Hoffman’s The Christian Prince [1882], and numerous others. His talent was especially suited to the representation of historical themes, or at least to stories set in some half-imagined past. A chronicler of the minutiae of artefacts, he brought a sense of journalistic conviction to his designs, converting even the fantastical into the plausible. As Gleeson White explains of his work for The Boys’ Own Magazine,he illustrated in a medievalist style, enhancing ‘historical romances’ with ‘spirit and no little knowledge of archaeological details’ (p.85). What is more surprising is his humour, a quality that sits uneasily next to his historical exactitude.

Through all of these commissions he continued to exhibit paintings. Early in his career he discovered an aptitude for seascapes and other marine subjects. From 1865 to 1891 he displayed a total of 47 maritime paintings in oil and watercolour at London venues including the Royal Academy, Suffolk Street and the fashionable Grosvenor Gallery (Graves, p.85). Examples can be found in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Institute of Civil Engineers, London, and the Maritime Museum, Liverpool; none has been exhibited in recent times. These works had a general audience, but Dudley’s interest in this genre was put to best use in his monumental series of chromolithographs for The Atlantic Telegraph (1866).

Last modified 18 November 2013