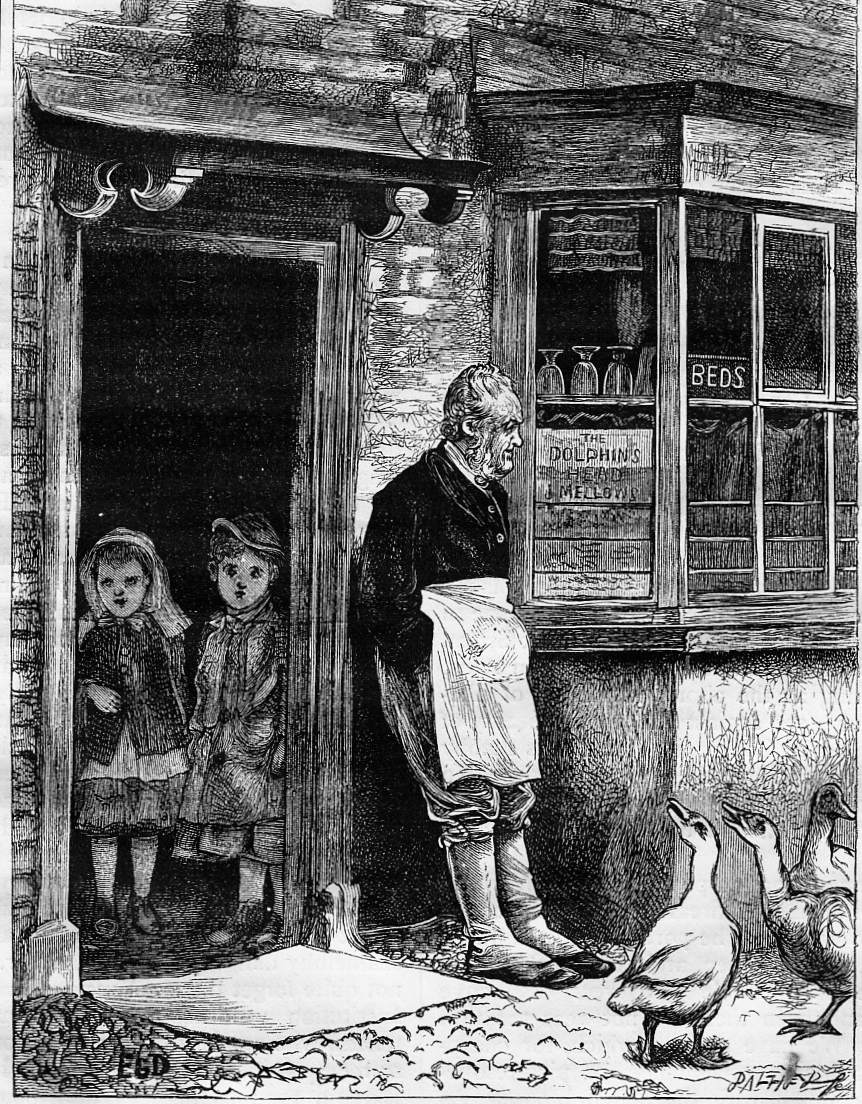

Mr. J. Mellows

Edward G. Dalziel

Wood engraving

Dickens's "Mr. J. Mellows," from "An Old Stage-Coaching House," chapter 22 in The Uncommercial Traveller, first published in 1 August 1863 in All the Year Round.

See commentary below

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passages Realized

Before the waitress had shut the door, I had forgotten how many stage-coaches she said used to change horses in the town every day. But it was of little moment; any high number would do as well as another. It had been a great stage-coaching town in the great stage-coaching times, and the ruthless railways had killed and buried it.

The sign of the house was the Dolphin's Head. Why only head, I don't know; for the Dolphin's effigy at full length, and upside down — as a Dolphin is always bound to be when artistically treated, though I suppose he is sometimes right side upward in his natural condition — graced the sign-board. The sign-board chafed its rusty hooks outside the bow-window of my room, and was a shabby work. No visitor could have denied that the Dolphin was dying by inches, but he showed no bright colours. He had once served another master; there was a newer streak of paint below him, displaying with inconsistent freshness the legend, By J. MELLOWS. [Chapter 22, "An Old Stage-Coaching House," p. 107]

My dinner-hour being close at hand, I had no leisure to pursue the goggles or the subject then, but made my way back to the Dolphin's Head. In the gateway I found J. Mellows, looking at nothing, and apparently experiencing that it failed to raise his spirits.

"I don't care for the town," said J. Mellows, when I complimented him on the sanitary advantages it may or may not possess; "I wish I had never seen the town!"

"You don't belong to it, Mr. Mellows?"

"Belong to it!" repeated Mellows. "If I didn't belong to a better style of town than this, I'd take and drown myself in a pail." It then occurred to me that Mellows, having so little to do, was habitually thrown back on his internal resources — by which I mean the Dolphin's cellar.

"What we want," said Mellows, pulling off his hat, and making as if he emptied it of the last load of Disgust that had exuded from his brain, before he put it on again for another load; "what we want, is a Branch. The Petition for the Branch Bill is in the coffee-room. Would you put your name to it? Every little helps."

I found the document in question stretched out flat on the coffee-room table by the aid of certain weights from the kitchen, and I gave it the additional weight of my uncommercial signature. To the best of my belief, I bound myself to the modest statement that universal traffic, happiness, prosperity, and civilisation, together with unbounded national triumph in competition with the foreigner, would infallibly flow from the Branch.

Having achieved this constitutional feat, I asked Mr. Mellows if he could grace my dinner with a pint of good wine? Mr. Mellows thus replied:

"If I couldn't give you a pint of good wine, I'd — there! — I'd take and drown myself in a pail. But I was deceived when I bought this business, and the stock was higgledy-piggledy, and I haven't yet tasted my way quite through it with a view to sorting it. Therefore, if you order one kind and get another, change till it comes right. For what," said Mellows, unloading his hat as before, "what would you or any gentleman do, if you ordered one kind of wine and was required to drink another? Why, you'd (and naturally and properly, having the feelings of a gentleman), you'd take and drown yourself in a pail!" [Chapter 22, "An Old Stage-Coaching House," p. 110-111]

Commentary

Despite the debate amongst Dickensians about the precise location of J. Mellows' establishment, The Dolphin, it is apparent from Dickens's account of his visit to the decaying markettown that the railway, the wonder of nineteenth-century technology and symbol of Britain's industry, has wrought less than positive changes upon the United Kingdom's smaller towns and villages. What probably led to the debate between several Dickensians in the late 1950s about the setting of the article was the fact that the old coaching inn called "The Dolphin's Head" is seven miles from the nearest railway station here, but that The George and Pelican not nearly so distant at Newbury in Berkshire. The location of the Newbury coaching-inn fits the circumstances of The Dolphin, for it

stood at the busy crossing of the Great Western Road between London and Bath and the road from Oxford to Winchester, in the parish of Speenhamland, and later became a popular choice for literary reflections on the departed glories of the coaching era, featuring in this capacity in Lord William Pitt Lennox's novel Percy Hamilton (1851) and in John Hollingshead's fine essay 'The Last Stage-Coach' — strikingly similar to Dickens's treatment collected in Odd Journeys In and Out of London (1860). Dickens had stayed at the George and Pelican in its heyday, putting up there on 7 November 1835 en route to report for the Moming Chronicle for a speech given by Lord John Russell in Bristol. He wrote to his fiancée Catherine Hogarth of 'a chaotic state of confusion just now' at the inn, being 'surrounded by maps, road-books, ostlers, and post-boys', before finishing with the postscript, 'I hear the Coach at this moment' (Pilgrim [Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens]' Vol. I, p. 90). Between this and the composition of the present paper, there is no instance in which he is known to have been in Newbury (thus Carlton's assertion that Dickens is writing about a return visit to Newbury 'made in the summer or Autumn of 1845' cannot be confirmed), but his frequent trips to the West Country to see his parents, or tours of public readings and amateur theatricals, are likely to have taken him there on several occasions. [Slater and Drew, p. 269-270]

Thus, despite the inn's distance from the railway station (an exaggeration to emphasize how the deserted Dolphin is a remnant of a bygone era), the prominence of "Mr. Pitt, hanging high against the partition" (108) would seem to connect this derelict inn in The Uncommercial Traveller with the celebrated George and Pelican at Newbury, although William Morton Pitt (1754-1836, Member of Parliament for Poole and Dorset) would have been the Pitt family member most closely associated with the old coaching-house, since it was the logical point at which to break his journey between Kingston Maurward House, near Dorchester, and London.

London was the main hub of coaching routes, but in the eighteenth century England already boasted a number of regional centres, notably Bristol, Birmingham, Salisbury, Shrewsbury, Oxford, Southampton, Northampton, Winchester, and Dorchester. By 1835, these centres of coach traffic had reached their zenith. The coming of the railway rapidly eclipsed stage-coaches, so that by 1854 there were, for example, only three coaches per week scheduled between London and Oxford, and coach services had been integrated with railway schedules, as one sees in Dickens's The Mystery of Edwin Drood, in which "Cloisterham" (Rochester) is not yet on a branch line, but has regular coach service to and from a railway station. Smaller centres such as Newbury in West Berkshire on the Great Bath Road declined in commercial importance with the arrival in the region of the Great Western Railway in 1847. The coming of the railways adversely affected river and canal traffic, and threw the once mighty turnpike system into disuse. As Dickens indicates in "An Old Stage-Coaching House," the revolution in overland transportation spelled economic collapse for for market towns such as Newbury because traffic tended to bypass the old town-centre in favour of communities with direct rail service to the larger centres.

The heyday of Newbury's George and Pelican coaching-inn complex was roughly a century (1740 through 1840), when the town served as a convenient overnight stop on the trip between Winchester, Bath, Bristol, and London. Within just a decade of the arrival of the railway, the Pelican was desolate, a sad and melancholy end (as Dickens's Uncommercial Traveller reflects) to a once-thriving establishment that had entertained Lord Nelson, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, King George III and Queen Charlotte, and even young reporter Charles Dickens.

Although Dickens mentions Mellows' offspring in the singular, Dalziel has given the proprietor two children, a boy and a girl of no more than six, who stand in the darkened doorway. Mellows himself pays no attention to either the children or the cackling geese at his feet, but seems to be regarding someone out of the right frame, perhaps the Uncommercial Traveller himself. Hands in his pockets, his spotless apron bespeaking a lack of trade, Mellows leans listlessly beside the doorway, as if contemplating the establishment's former glories when carriages were constantly arriving and departing — before the Age of Steam destroyed the Dolphin's economic viability. In his treatment of this selfsame chapter, C. S. Reinhart in the American Household Edition has depicted instead an old turnpike-keeper, again with the intention of dramatising the sudden collapse of the transportation system that had flourished from the late seventeenth century right up to the 1840s, when the coming of the railways to south-western England destroyed coaching firms and turnpikes alike. Like Dalziel's innkeeper Reinhart's turnpike-keeper lacks both customers and a purpose in life.

Other urban scenes

- Poor Mercantile Jack

- Mr. Grazinglands looked in at a pastry cook's window

- Blinking old men . . . let out of workhouses

- He was taken into custody by the police

- It was agreed that Mr. Batten "ought to take it up"

- Look at this group at a street corner

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller, Hard Times, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood. Il. Charles Stanley Reinhart and Luke Fildes. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Dickens, Charles. The Uncommercial Traveller. Il. Edward Dalziel. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1877.

Scenes and Characters from the Works of Charles Dickens; being eight hundred and sixty-six drawings, by Fred Barnard, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz); J. Mahoney; Charles Green; A. B. Frost; Gordon Thomson; J. McL. Ralston; H. French; E. G. Dalziel; F. A. Fraser, and Sir Luke Fildes; printed from the original woodblocks engraved for "The Household Edition." New York: Chapman and Hall, 1908. Copy in the Robarts Library, University of Toronto.

Slater, Michael, and John Drew, eds. Dickens' Journalism: 'The Uncommercial Traveller' and Other Papers 1859-70. The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens' Journalism, vol. 4. London: J. M. Dent, 2000.

Victorian

Web

Charles

Dickens

Visual

Arts

Illustration

The Dalziel

Brothers

Next