"No beggars implored him to bestow a trifle". Charles Edmund Brock (1870-1938). (1905). Charles Dickens. A Christmas Carol. (1905). Headpiece, 7.2 cm by 7.5 cm, vignetted. (3) Click on image to enlarge it.

Passage Illustrated

Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grind-stone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster. The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shriveled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. A frosty rime was on his head, and on his eyebrows, and his wiry chin. He carried his own low temperature always about with him; he iced his office in the dogdays; and didn't thaw it one degree at Christmas.

External heat and cold had little influence on Scrooge. No warmth could warm, no wintry weather chill him. No wind that blew was bitterer than he, no falling snow was more intent upon its purpose, no pelting rain less open to entreaty. Foul weather didn't know where to have him. The heaviest rain, and snow, and hail, and sleet, could boast of the advantage over him in only one respect. They often "came down" handsomely, and Scrooge never did.

Nobody ever stopped him in the street to say, with gladsome looks, "My dear Scrooge, how are you? When will you come to see me?" No beggars implored him to bestow a trifle, no children asked him what it was o'clock, no man or woman ever once in all his life inquired the way to such and such a place, of Scrooge. Even the blind men's dogs appeared to know him; and when they saw him coming on, would tug their owners into doorways and up courts; and then would wag their tails as though they said, "No eye at all is better than an evil eye, dark master!" [Stave One, "Marley's Ghost," 4-5]

Commentary

E. C. Brock, who had an extensive program of illustration to complete, sets the keynote with a line-drawing that shows how Scrooge's lack of empathy prevents him from relating to others. The grimy beggar's agitation adds another dimension to the little street scene (Brock’s few details suggest a street; the sweeper's brush and the typical cast iron marker for the edges of a borough). John Leech, the first illustrator of A Christmas Carol (1843) whose assignment included only eight images, did include such a scene. Other illustrators, however, recognized the importance of establishing the protagonist as a curmudgeon in order to make his redemptive transformation all the more heart-warming. In the 1910 Charles Dickens Library volume of The Christmas Books, Harry Furniss in Scrooge Objects to Christmas (see below) includes a vignette of the inveterate miser rejecting the advances of the charity-collectors to make the same point that Brock makes here. Scrooge, like Thomas Gradgrind in Hard Times for These Times (1854) is a man of facts, not sentiment, when the story opens, and he recognizes a humbug when he sees him. Here the humbug recognizes that he would be wasting his time appealing to so unsentimental a passerby as Scrooge. Even though the well-dressed businessman certainly possesses the means to be charitable, that is not his inclination.

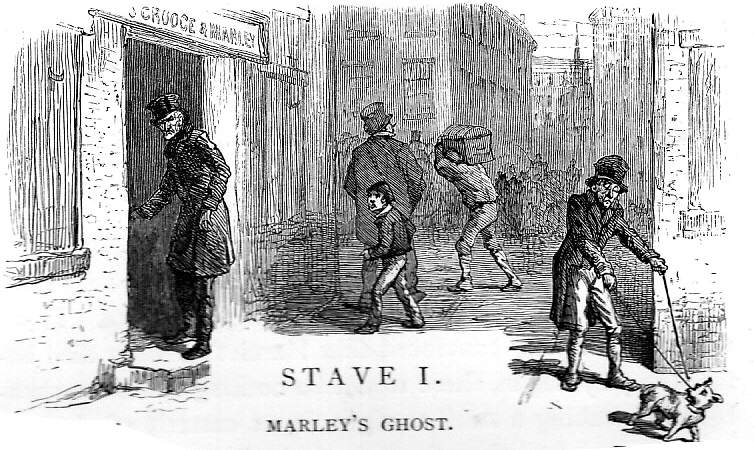

Whereas the narrator stipulates a negative — that no beggar is prepared to undertake the challenge of soliciting spare change from the formidable miser — the illustrator must demonstrate that reluctance on the face of a beggar, whom E. C. Brock depicts as a crossing-sweeper. Previous illustrators after Leech have generally shown Scrooge's uncharitable, anti-Christmas sentiment by depicting him interacting with the local charity collectors, with his nephew, and with his clerk. Charles Green's approach is as novel as Brock's since the illustrator of the Pears edition depicts a solitary but apparently complacent Scrooge absorbed in reading the evening paper, perhaps the financial or business section. But the person who must tolerate Scrooge's parsimonious disposition more than any other is Bob Cratchit, as Fred Barnard demonstrates in the 1878 Household Edition illustration "It's not convenient," said Scrooge, "and it's not fair. If I was to stop half-a-crown for it, you'd think yourself ill-used, I'll be bound?" (see below). With a more extensive program of illustration in his 1868 volume, Sol Eytinge, Junior, could underscore Scrooge's crusty exterior and anti-Christmas sentiments in a number of scenes, including one with Bob Cratchit and another with the charity-collectors, but beginning with a situation-establishing view of Scrooge's counting house in the City, "Scrooge and Marley's," vignette for "Stave I. Marley's Ghost" (see below). Brock's approach, in contrast, is both more economical and more humorous, as he depicts the scruffy, ill-clad crossing-sweeper obviously agitated by the approach of the well-dressed Scrooge. Here, then, is the economic context of the tale, the Hungry Forties, epitomized in the figures of the affluent capitalist and a middle-aged, under-employed member of the proletariat.

Relevant Illustrations from the 1843 and later Editions

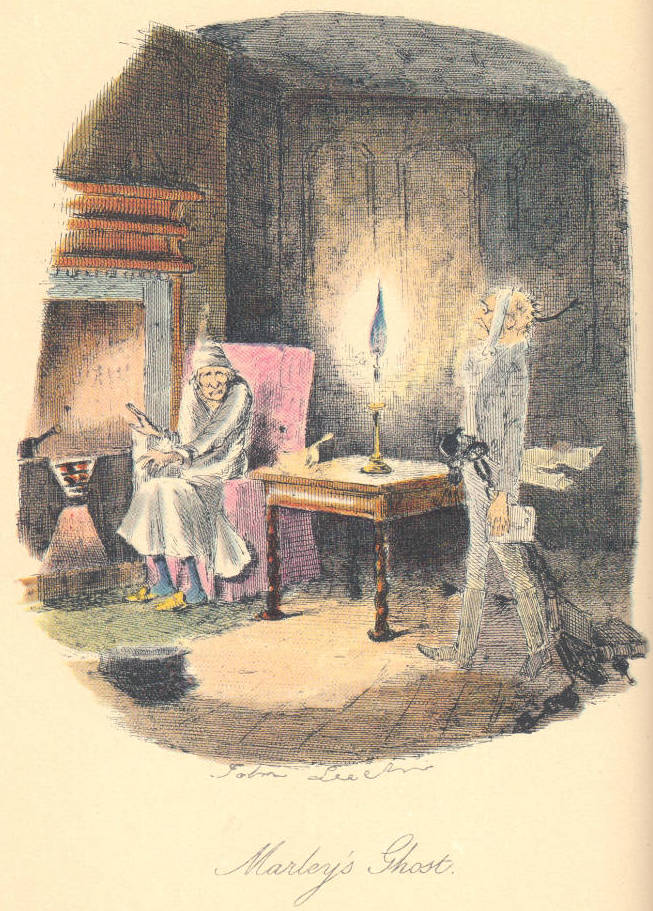

Left: Leech's interpretation of Scrooge's meeting the ghost of his former partner, Marley's Ghost. Right: Charles Green, the business-oriented, solitary dinner of the miser, Scrooge's Christmas eve, in the 1912 Pears volume.

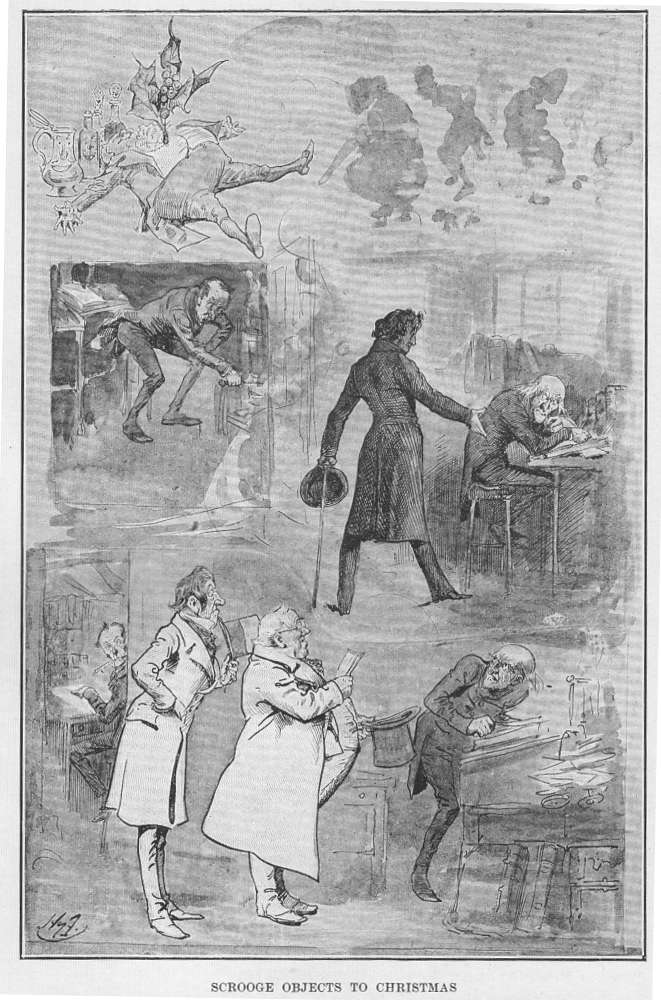

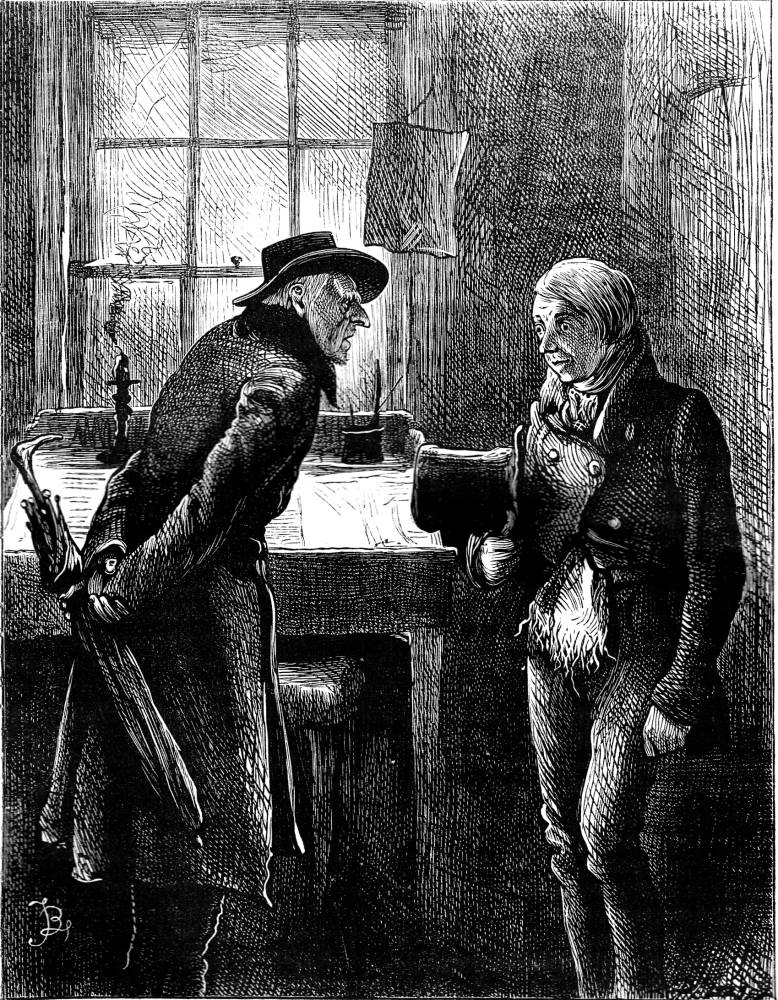

Left: Furniss's composite scene in which a Scrooge overflowing with anti-Christmas sentiment scowls at his nephew, Scrooge objects to Christmas (1910). Right: Barnard's dramatisation of Scrooge's attitude towards Christmas, "It's not convenient," said Scrooge, "and it's not fair. If I was to stop half-a-crown for it, you'd think yourself ill-used, I'll be bound?" (1878)

Above: Sol Eytinge, Junior's headpiece establishing Scrooge's business persona, "Scrooge and Marley's," vignette for "Stave I. Marley's Ghost" (1868).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Dickens, Charles. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1878.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London & Glasgow: Collins' Clear-Type Press, 1906.

_____. Christmas Books. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. London: Chapman and Hall, 1843.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1868.

_____. A Christmas Carol and The Cricket on the Hearth. Illustrated by C. E. [Charles Edmund] Brock. London: J. M. Dent, 1905; New York: Dutton, rpt., 1963.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Charles Green, R. I. London: A. & F. Pears, 1912.

_____. A Christmas Carol. Illustrated by Arthur Rackham. London: William Heinemann, 1915.

_____. A Christmas Carol in Prose, Being A Ghost Story of Christmas. Illustrated by John Leech. (1843). Rpt. in Charles Dickens's Christmas Books, ed. Michael Slater. Hardmondsworth: Penguin, 1971, rpt. 1978.

_____. Christmas Stories. Illustrated by E. A. Abbey. The Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1876.

Guiliano, Edward, and Philip Collins, eds. The Annotated Dickens. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1986. Vol. 1.

Hearn, Michael Patrick, ed. The Annotated Christmas Carol. New York: Avenel, 1976.

Created 18 September 2015

Last modified 15 March 2020