Many thanks to the Museum and Study Collection at Central Saint Martins, and to Brian Clift and Philip Pankhurst, for permitting the reuse of their photographs from Flickr and Geograph respectively under the Creative Commons Licence. Remaining photographs and scans either from our own website or by the author. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on all images to enlarge them, and for more information where available.]

Early Life and Career

William Richard Lethaby (1857-1931) trained and practised as an architect, but was also, and more importantly, a designer, an educator, and an architectural theorist and historian. Picking up the baton from A. W. N. Pugin, John Ruskin and William Morris, he saw architecture as "the synthesis of the fine arts, the commune of all the crafts" (Architecture, 1), and inspired a holistic approach to it. His name may not be as familiar to the general public as the names of his predecessors, but it should be: a pivotal figure, he had a great influence on art education and the Arts and Crafts movement of late Victorian Britain, and arguably as great a one on modernist design in Europe in the early twentieth-century.

Lethaby was born into a working-class family at Barnstaple in Devon on 18 January 1857, the second child and only son of Richard Pyle Lethaby, a carver and gilder, and his wife Mary. From earliest childhood he was exposed to principles that would later be reinforced from other sources. His father, a committed Bible Christian, was the "very pattern of the respected and respectable working man, so much admired by his sober fellow Victorians — authoritarian, unbending, devout, a fine and careful craftsman with a head for business, but a Radical nevertheless" (Rubens 15). Architecture would demand of Lethaby, later on, just what he would expect it to demand from others — not simply the particular skills of the profession, but dedication, and above all the ability to infuse intelligent design with moral and spiritual values. Something of all this was summed up when he said, in one of his famously quotable pronouncements, "Modern architecture, to be real, must not be a mere envelope without content" (Architecture, 7).

The young Lethaby's highly accomplished winning entry for the Soane Medallion Competition: "A House for the Learned Societies." Courtesy of the Museum and Study Collection at Central Saint Martins.

Right from the start, Lethaby seemed destined for a life in the applied arts. Like budding artists of all kinds at this time (another was the illustrator Kate Greenaway), he benefited from local evening classes run as part of Henry Cole's national incentive for art education. He was then apprenticed at the age of fourteen to Alexander Lauder, a Barnstaple architect with a wider interest in the arts. Lauder wanted all his workmen to understand each other's crafts and feel involved in the final product, and his new apprentice flourished under his tutelage. By the age of seventeen, Lethaby was contributing his drawings to the architectural press, and he soon began to prove his exceptional talent by winning awards. The most important of these would be the Soane medallion of the Royal Institute of British Architects in 1879, and the Pugin Travelling Scholarship in 1881 — he would travel widely in Britain, France and elsewhere, even, in 1893, going as far as Constantinople.

Architectural Work

Left to right: (a) A view of Cragside in Northumberland . Lethaby was Shaw's assistant when he was working on this in the 80s, and is known to have designed the elaborate marble chimney-piece in the drawing-room. (b) Lethaby's (former) Eagle Insurance Building, 122-24 Colmore Row, Birmingham. Photograph © copyright Brian Clift. (c) All Saints', Brockhampton. Photograph © copyright Philip Pankhurst. [The last two are both slightly modified from their originals.]

Lethaby's career was advancing steadily during these years. After a spell with the architect Richard Waite in Derby, he moved to London. He had expected to enter the office of William Butterfield, but the arrangement was cancelled on the grounds that entering competitions was disruptive to work — and perhaps also because Butterfield disapproved of an unusual cemetery chapel that the young man had designed (see Rubens 32). Instead, Lethaby was picked up by Richard Norman Shaw, who had been quick to spot his potential, and had enough confidence in him to give him his head: "to no other assistant did Shaw extend the freedom enjoyed by Lethaby," says his biographer Godfrey Rubens (39). The story goes that, having become Shaw's chief assistant early in his twenties, he was once referred to by someone else as his pupil. "'No,' Shaw replied, 'on the contrary it is I who am Lethaby's pupil" (qtd. in MacCarthy). Lethaby worked with Shaw for ten years (1879-1889) on important and influential buildings like Cragside for the industrialist Lord Armstrong in the early 1880s, and the former New Scotland Yard building at Derby Gate, Westminster, which was completed in 1891.

20 Calthorpe Street, Bloomsbury, off the Gray's Inn Road, where Lethaby lived from 1880 to 1891, with its blue plaque.

In 1889, while living at 20 Calthorpe Street, Bloomsbury, Lethaby set up practice in Bloomsbury on his own account. He only saw a few projects through, mostly large country houses, but they were, as might be expected, quite distinctive. One was Melsetter House in the Orkneys, which Morris's younger daughter May described as "a sort of fairy palace on the edge of the great northern seas ... full of homeliness and the spirit of welcome" (qtd. in Rubens 138). Another was High Coxlease in Lyndhurst, Hampshire. Lethaby's American wife Edith, whom he had met on the Constantinople trip and finally married in 1901, warmed to as soon as she saw it: "Everything is a very happy combination of the artistic and the practical" (qtd in Rubens 148). But his two best regarded works are the Eagle Insurance Building in Birmingham (1900), where he succeeded in the expression rather than camouflage of his modern materials (reinforced concrete and steel); and the supremely sturdy and serene All Saints' Church at Brockhampton, Herefordshire (1902). These Grade 1 listed buildings can both be seen as embodying his theories, celebrating, in effect, "the structural form itself" (Hart 155). The latter, with its dramatic planes both inside and out, is not at all as traditional as it first appears, and was fraught with difficulties in the building, so much so that it may have encouraged Lethaby to focus on his new role as educator. Yet Nikolaus Pevsner has described the end result as "one of the most convincing and most impressive churches of its date in any country" (90; retained verbatim in Brooks and Pevsner 138).

Lethaby and Westminster Abbey

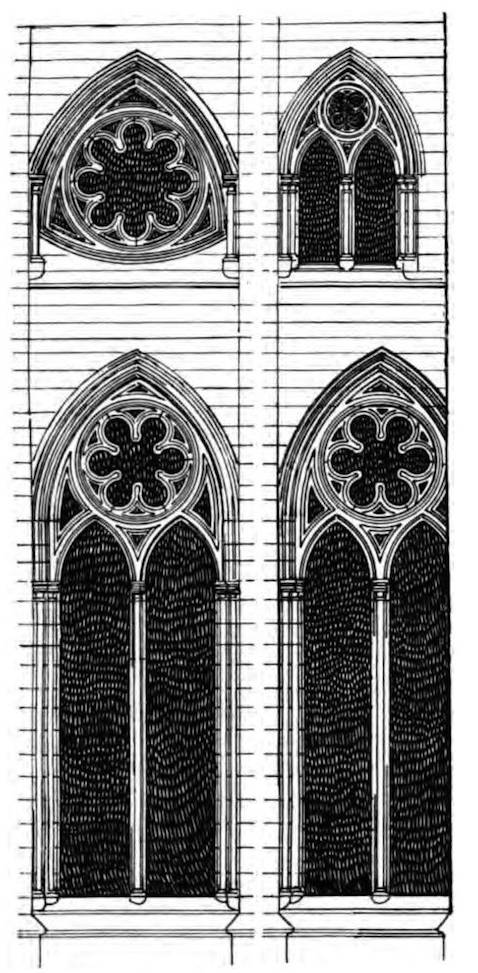

Arrangement of Windows in Apsidal Chapel, in Westminster Abbey & the King's Craftsmen: A Study of Mediaeval Building, facing p. 135.

Another strand of Lethaby's complex career structure was his association with the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings. He became a member of it soon after joining Shaw, and it brought him into contact with not only Morris but also the architect Philip Webb, who became a close friend, and was the subject of one of his later books. Lethaby wrote in 1922, "The happy chance of close intimacy with Philip Webb the architect, at last satisfied my mind about that mysterious thing we call 'architecture.' From him I learnt that what I was going to mean by architecture was not mere designs, forms, and grandeurs, but buildings, honest and human, with hearts in them" (qtd. in Noppen 536). The society itself gained much from Lethaby's involvement with it. Appointed in 1906 to the role of surveyor to the dean and chapter of Westminster Abbey, he was able to put the society's policy into practice by concentrating on maintenance and careful cleaning, saying right from the start that he would not interfere even with earlier work on it that he thought misconceived: "Now it is done don't alter it; I would not meddle even with the restoration of a restorer" (Westminster Abbey, 78). But, in bringing to light lost colour, for example, he showed how much could be achieved by his methods. As a result, his influence "spread far beyond Westminster"; he became "the recognized supreme authority on the care of old buildings" (Noppen 536).

Lethaby as Educator and Inspiration

Left to right: (a) The premises of the Central School of Art and Design, later St Martin's, on Southampton Row, WC1 (now vacant). 1905-08. (b) Figure over the corner entrance, bearing the arms of the City of London and St George, and the motto, "Labor Omnia Vincit." (c) Blue plaque commemorating Lethaby's tenure as principal.

As indicated above, despite being surveyor to the Abbey, Lethaby had now turned away from the practice of architecture, becoming instead "the greatest single influence on art education during this period" (Osborne 50). As one of the driving forces behind the establishment of the London County Council Central School of Arts and Crafts in 1896, he had some input into the design of its new premises in Southampton Row. It should, he said, be "plain, reasonable, and well-built, with as little of common-place of so-called ornament as maybe" (qtd in Rubens 170). The sculptured shield at the corner entrance is restrained, dignified and (with its emphasis on effort), meaningful. In his own role here, he himself was indefatigable, running the School for six years before being officially appointed its first principal. Through his determined emphasis on practical training in the various crafts, he "affected the whole direction of twentieth-century European design education.... The Bauhaus, when it opened in 1918 in Weimar, was set up on similar lines" (MacCarthy). As if that were not enough, in 1900 he had also become the first professor of design at the prestigious Royal College of Art (the name since 1896 of the National Art Training School) in South Kensington.

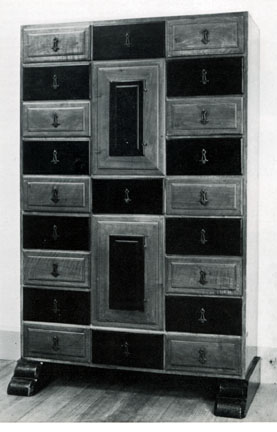

Walnut and ebony cabinet by Ernest Gimson, c.1905.

But there was still another way in which Lethaby exerted a direct, hands-on influence on late Victorian and early twentieth-century design. In 1884 he was one of the prime movers in the foundation of the Art Workers' Guild, which David Crowley aptly describes as "the conscientious core of the Arts and Craft Movement" (134). He was equally involved in the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society which grew out of it in 1888. Then, in the following year, he set up a furniture firm with Ernest Gimson (1866-1919) and others. The enterprise proved short-lived, closing down in 1892. Even so, it has its importance: some of those drawn into in it, like Gimson himself, "became the most influential of the Arts and Crafts furniture designers" (Osborne 50). It was fitting, therefore, that in 1911, the same year that he resigned from the Central School, Lethaby should serve a term of office as master of the Art Workers' Guild — a body which is still very much in existence today. Thus, along with Morris, and for many years after Morris's death in 1896, Lethaby was at the very heart of a highly creative world in which many different craftsmen of all types made their names (see Watkinson 25). His involvement in it, and encouragement of it, both helped it to flourish.

Where Lethaby departed from the Morris tradition (and from Gimson) was in his eventual promotion of craft values in industrial design. This was a difficult row to hoe, but he had become convinced of the need for it, and to consider it possible from his own experience — perhaps particularly during the planning and construction the Eagle Insurance Building. His support for the formation of the Design and Industries Association, which he helped found in 1915, was a brave move for one so intimately associated with the Arts and Crafts Movement, and seems to have been a factor in what was, in effect, his "forced retirement" from the Royal College of Art in 1918 (Rubens 230).

Lethaby as Author

Three of the hundreds of line drawings and diagrams Lethaby drew for many his books. Left to right: (a) Font, Brookland, Kent , in Leadwork (1893), p. 54. (b) Longitudinal section, having regard to Dome as first built. The Church of Sancta Sophia (1894), facing p.30. (c) Byzantine Capital from the Mosque of Damascus, frontispiece of Mediaeval Art from the Peace of the Church to the Eve of the Renaissance, 312-1350 (1904).

Lethaby spread his ideas not only by getting like-minded and talented people together and giving them talks, lectures and guidance, but also by publishing an immense number of articles and books. The articles appeared in journals like Archaeologia, and the books, generally illustrated with his own drawings, covered the whole range of his interests. The first and perhaps best known was Architecture, Mysticism and Myth (1891), which baffled many of its earliest readers, including the Times reviewer in his "Books of the Month" column: "His insight is so esoteric that, to plain people, its deliverances are simply unintelligible" (4). But it but proved seminal within the profession itself. The attempt to show that both "structure and ornament had meaning, and that style is not merely a question of choice" (Garnham 31) had a great influence on other architects like, for example Charles Harrison Townsend. More prosaic but equally inspiring in another way, and perhaps looking forward to his later views about art and industry, Leadwork: Old and Ornamental and for the Most Part English (1893) includes chapters on the fine craftsmanship that can give beauty even to such details as gutters and pipe-heads, while Lethaby's next book, The Church of Sancta Sophia: A Study of Byzantine Building (with Harold Swainson, 1894), encouraged the growing interest in Byzantine forms and decoration. Indeed, J. F. Bentley, architect of London's best-known Byzantine landmark, Westminster Cathedral, took the newly-published book abroad with him on a study tour after getting the commission for designing his magnum opus. Forced to stay away from Constantinople because of the prevalence of cholera there, he comforted himself by saying that San Vitale in Ravenna, and Lethaby's book, told him all he needed to know anyway (de l'Hôpital 35). Lethaby would later write the introduction to the book about the cathedral written by Bentley's daughter.

As an architectural historian as well as a theorist, Lethaby seemed equally at home describing the medieval arts of London (Londinium, Architecture and the Crafts, 1923), and those of Europe and the Mediterranean (Mediaeval Art from the Peace of the Church to the Eve of the Renaissance, 312-1350 (1904, revised ed. 1912). Other notable publications among the many (see Rubens 303-12 for the extraordinarily long list) include his later Westminster Abbey Re-examined (1925), and Philip Webb and his Work, which was published in book form only posthumously, in 1935.

Death and Reputation

Noel Rooke's portrait of Lethabay surrounded by silhouettes of some of the buildings with which he was associated, including Westminster Abbey, top left. Rooke, an early student of Lethaby's, became Vice-Principal of the Central School (Rubens 189). Courtesy of the Museum and Study Collection at Central Saint Martins.

Lethaby had been intensely shy as a boy, and a part of him seems always to have remained withdrawn: Rubens suggests that he was marked for life by a repressive Victorian upbringing (278-79). Yet he had a number of close friendships, and won the respect and affection of peers and pupils alike. His wife Edith died in 1927, and Lethaby was buried with her in 1931 in the churchyard at Hartley Wintney in Hampshire, where they had lived for a while after his retirement from the Royal College. Having married rather late, they had remained childless, but there were many to carry on Lethaby's legacy. As well as having two blue plaques in London, he is commemorated by a stone in the pavement of the west walk of the Great Cloister at his beloved Westminster Abbey.

Spanning the late Victorian and early modern period, and effectively two careers, Lethaby has not always been given his due. Early twentieth century critics did acknowledge his influence, with Reginald Turnor, for example, deciding that as well as being "a sort of literary mystic of architecture" (105) he came nearer than contemporaries like Voysey and Mackintosh to being "a pioneer of modernism" (107). But full recognition only came later, explains Fiona MacCarthy, when design history emerged as a popular area of study in the 1970s. Now, she suggests, his "intense appreciation of the buildings of the past and his urge to relate past experience to the present" allow him to be seen as "the most important theoretician of design and architecture in the first quarter of the twentieth century." She credits his vast output of writings and lectures over five decades with being "the most impressive body of sustained design polemic since John Ruskin," and, looking forward rather than back, claims that from his "brilliantly concise, impassioned writings emerged the concept 'form follows function,' which dominated European modernist design." Clearly, these writings — and his actual practise in so many spheres — were not the only links in the chain, but they were some of the last and most forcefully and widely disseminated ones.

Related Material

Bibliography

Backemeyer, Sylvia and Theresa Gronberg, eds. W.R. Lethaby, 1857-1931: Architecture, Design and Education. London: Lund Humphries, 1984. (Catalogue of an exhibition held by the Central School of Arts and Crafts and the Cheltenham Art Gallery and Museum, as a "long overdue tribute" to this "forceful disciple of Pugin, Ruskin and William Morris" (7). Print.

"Books Of The Week." The Times, Thursday 31 December 1891: 4. Times Digital Archive. Web. 15 September 2013.

Brooks, Alan, and Nikolaus Pevsner. Herefordshire. The Buildings of England. New Haven: Yale, 2012. Print.

Crawley, David. Introduction to Victorian Style. Royston, Herts.: Eagle Editions, 1998. Print.

de l'Hôpital, Winefride. Westminster Cathedral and Its Architect: Volume I, The Building of the Cathedral. 2 vols. London: Hutchinson, 1919. Internet Archive. Web. 15 September 2013.

Garnham, Trevor. "William Lethaby and the Two Ways of Building." Architectural Association Files. No. 10 (Autumn 1985): 27-43. Accessed via JSTOR. Web. 15 September 2003.

Greensted, Mary, ed. An Anthology of the Arts and Crafts Movement: Writings by Ashbee, Lethaby, Gimson and Their Contemporaries. London: Lund Humphries, 2005. Print.

"Handwork versus Machine Production." Ernest Gibson and the Arts & Crafts Movement in Leicester. Web. 15 September 2013.

Hart, Vaughan. "William Richard Lethaby and the 'Holy Spirit': A Reappraissal of the Eagle Insurance Company Building, Birmingham." Architectural History. Vol. 46 (2003): 145-158. Accessed via JSTOR. Web. 15 September 2003.

Kay, John. "W. R. Lethaby at the Central School." William Morris Journal. 6.3 (Summer 1985): 36: 26-30. Web. 15 September 2013.

Lethaby, W. R. Architecture, Mysticism and Myth. New York: Macmillan, 1892. Internet Archive. Web. 15 September 2013.

_____. Leadwork: Old and Ornamental, and for the most part English . London & New York: Macmillan, 1893. Internet Archive. Web. 15 September 2013.

_____. Mediaeval Art from the Peace of the Church to the Eve of the Renaissance, 312-1350. London: Duckworth, 1904. Internet Archive. Web. 15 September 2013.

_____. Westminster Abbey & The King's Craftsmen: A Study of Mediaeval Building. London: Duckworth, 1906. Internet Archive. Web. 15 September 2013.

Lethaby, W. R. and Harold Swainson. The Church of Sancta Sophia, Constantinople: A Study of Byzantine Building. London & New York: Macmillan, 1894. Internet Archive. Web. 15 September 2013.

MacCarthy, Fiona. "Lethaby, William Richard (1857-1931)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Current online ed. Web. 15 September 2013.

Noppen, John George. "Lethaby, William Richard (1857-1931)." Dictionary of National Biography. Fifth Supplement (1931-40) (1949). Internet Archive. Web. 15 September 2013.

Osborne, Harold, ed. Oxford Companion to the Decorative Arts. London: Oxford University Press, 1985. Print.

Pevsner, Nikolaus. Herefordshire. The Buildings of England. London: Penguin, 1963. Print.

Rubens, Godfrey. William Richard Lethaby: His Life and Work. 1857-1931. London: The Architectural Press, 1986. (Still the standard account.) Print.

Turnor, Reginald. Nineteenth Century Architecture. London: Batsford, 1950.

Watkinson, Ray. "Godfrey Rubens's Lethaby" (well-informed book review). William Morris Journal. 7.1 (Autumn 1986): 68: 25-35. Web. 15 September 2013.

Last modified 16 September 2013