[This material comes from Chapter 4, "Candle-light and Candlesticks," in Gertrude Jekyll's Old West Surrey: Some Notes and Memories (1904). I believe these are all her photographs. GPL]

IN these days of cheap matches and lamps for mineral oil, one can hardly realise the troubles and difficulties in the way of procuring and maintaining artificial light for the long dark mornings and evenings of nearly half the year, that prevailed among cottage folk not a hundred years ago. Till well into the third or fourth decade of the nineteenth century, many labouring families could afford nothing better than the rush-lights that they made at home, and this, excepting fire-light, had been their one means of lighting for all the preceding generations.

In the summer, when the common rushes of marshy ground were at their full growth, they were collected by women and children. The rush is of very simple structure, white pith inside and a skin of tough green peel. The rushes were peeled, all but a narrow strip, which was left to strengthen the pith, and were hung up in bunches to dry. Fat of any kind was collected, though fat from salted meat was avoided if possible. It was melted in boat-shaped grease-pans that stood on their three short legs in the hot ashes in front of the fire. They were of cast-iron;.made on purpose. The bunches, each of about a dozen peeled rushes, were drawn through the grease and then put aside to dry.

Left: Cast-iron grease Pans. Right: Rush-lights after being dipped in grease. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

An old cottage friend told me all about it, and though she ninety years of age, yet, when next I want to see her, she had gone out and found some rushes to show me how it was done. 'You peels away the rind from the peth, leaving only a little strip of rind. And when the rushes is dry you dips 'em through the grease, keeping 'em well under. And my "mother she always laid hers to dry in a bit of hollow bark. Mutton fat's the best; it dries hardest."

Rush-light holders were mostly same pattern as to the way the jaws held the rush, the chief variation being in the case of the spring holders, which were the latest in date. In these the jaws were horizontal. But the usual and older pattern had the jaws upright, their only difference being in the shape and treatment of the free end of the movable jaw and the shape of the wooden block. The counter-balance weight was formed either into a'knob or a curl. Occasionally, it had somewhat the shape of a candle-socket. Later, when tallow dip-candles came into use, the counterbalance was made into an actual candle-socket.

Left: Rush-light holders, the tallest 9 1/2 inches. [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

The rush-light was held as shown. When it was a long one a piece of paper or rag was laid on the table to keep it from being greased by the tail of the rush. ' We set it on something so as not to mess about,' as my old friend said. About an inch and a half at a time was pulled up above the jaw of the holder. A rush-light fifteen inches long would burn about half-an-hour. The frequent shifting winter was only just over, and the rushes barely grown, and was the work of a child. It was a greasy job, not suited to the fingers of the mother at her needlework. 'Mend the light,' or 'mend the rush ' was the signal for the child to put up a new length.

Two pins crossed would put out a rush-light, and often cottagers going to bed — their undressing did not take long — ould lay a lighted rush-light on the edge of an oak chest or chest of drawers, leaving an inch over the edge. It would burn up to the oak and then go out. The edges of old furniture are often found burnt into shallow grooves from this practice.

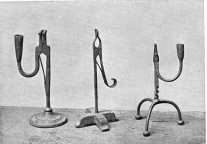

Left: Rush-light in its holder. Middle: Standing rush-light and candle holders. Right: Wooden standing rush-light holders.

There were several kinds of tall rush-light holders to stand on the floor, both of wood and iron. The iron ones have nearly always a candlesocket in addition, indicating a later date, and the same kind of spring arrangement to'allow of the light being adjusted to the right height. Unless all of iron, as in the three-legged one in the illustration, they nearly always had the cross-shaped block for a foot. [101-07]

Bibliography

Jekyll, Gertrude Old West Surrey: Some Notes and Memories. London: Longmans, Green, & Co, 1904.

1 February 2009