Using the Internet Archive version of The Studio, George P. Landow proofed, formatted, and linked Wood's article on the sculptor. This essay, whose Edwardian sexist condescension makes very annoying reading indeed, has the value of recording Levick's work. Given the very masculine subjects of her sculptures of a young Rugby player tackling the ballcarrier and powerful men wrestling, it strikes me as surprising and sad to see how conventionally feminine much of her work became after leaving the Royal Academy. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

How rarely is the femininity that gives to a woman's art its value, its interest as a point of view, to be met with! With their impressionability of temperament women drift easily into imitation; the receptivity of mind that makes them clever students takes from their art its reliance on itself: gives in exchange this plausible imitation. For women's art to be individual is for it to be feminine, and when it is feminine it gives gracious expression to the subtleties of sentiment that belong to women; it provides them with an added means of expressing the artistry that is unconsciously in their possession. The artistic material that they choose receives from their hands an exquisiteness in exchange for strength; it gains its feminine emphasis from the delicate taste and refinement of fancy which in every department of their life erects a fragile barricade of beauty between their thoughts and ours. Where so much charm is contained as there is in femininity in art, it is more than a thousand pities that so many women artists should forsake the qualities which they could easily give to their work in struggling ambitiously after achievements in which,” by the nature of things, men easily dominate.

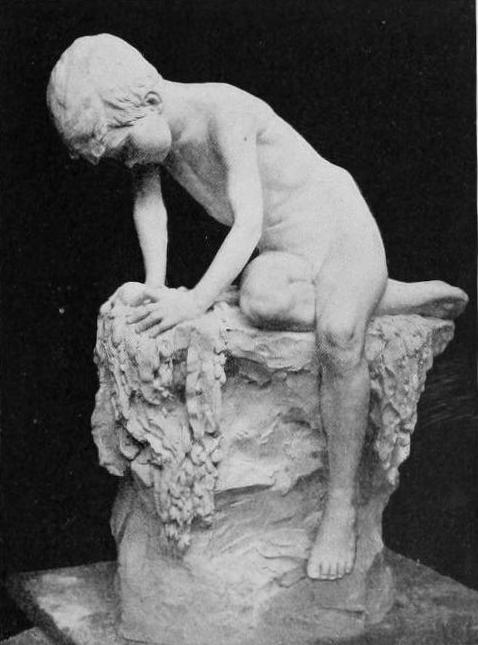

Asleep in the arms of the slow-swinging sea. Right: The Sea Urchin

Where woman is content that her art should be first of all expressive of her delicate instincts about life, of her intimate tenderness towards it, towards what is fleeting and fragile — as, for instance, the faces of children and the shapes of flowers — upon these lines her art becomes in itself a flower of exquisite value, filling a definite place as the flower fills it in the scheme of things. Where it is perfected in its expression it becomes in its sweetness as endurable as man's art is in its strength. In attempting to find simple and natural expression in art for herself, Miss Levick, in each thing she produces, reveals the intimate qualities that we so much prize. From the moment when success in the schools ceased to be of immediate consequence to herself, her art freed itself from any competition for those qualities in her work which always in the end remain at their best with men. To have striven for some time after such qualities laid for the real qualities of her art an admirable foundation; unconsciously she drifted into work charming in its limitations, but not until she had proved her willingness to face the difficult technique of her profession without any evidence of the pitfalls it holds for the uncourageous and the untrained. Her career at South Kensington bears witness to her patient study there, and her refusal to be beaten by the first difficulties that are always laid between an artist having something to express and the ignorance which so effectually silences any effectual ex pression. For about eight years Miss Levick studied under Mr. Lanteri at Kensington, and she acknowledges a great debt to him for all he taught her. She won a free studentship about a year after her admission to the schools. In 1897 the Princess of Wales Scholarship was awarded her, and a group of Boys Wrestling won her a gold medal in the National Competition, before gaining her the British Institution Scholarship for Modelling in 1896, in competition for which scholarship the group had been designed. The group was exhibited in the Royal Academy in the following year, where Miss Levick has since exhibited nearly every year. Other medals and awards marked her progress as that of a brilliant student, but it is just where all such things leave off that the real test comes. Miss Levick has since endowed her art with personal qualities that give it a more than usually interesting and a remarkably promising place amongst the work of our younger contemporary sculptors.

Left to right: (a) Brian. (b) Our Lady and St. Edmund. (c) [Fairy and flower].

Miss Levick could hardly help being interesting in her art, since even trying commissions, commissions affording little scope for a personal rendering of things, have been executed by her in a quite individual manner; and where, as in the decorations for the little Catholic chapel at Hunstanton in Norfolk, a congenial task has been given to her, she has expressed in her work high qualities of emotional intention that override the rare faults in design which here and there give to its significant beauty a limitation. The face in the side panel of Our Lady is very expressive of the qualities which give a charm that must last to Miss Levick's work. In it there is conveyed with great simplicity and with tenderness a face that in its gentleness realises in a modern spirit the oldest tradition. It has the particular gentleness that can be given to a face by woman's hand alone. In the corresponding panel of St. Edmund a certain lack of feeling in the drapery is not qualified so easily” by the face. In the work for St. Brelades, Jersey, the design needs no qualification. The reredos panel frames the heads of Cherubim which are tenderly abstracted from it, as tenderly as the heads in the relief called Sleep, which relief is as good an example as any of handling which is informed with a sympathy that becomes as strength in proportion as the artist enables us to feel it. It is impossible to look for more than a few minutes at these two faces — little more than half of one only revealed to view — and not to enter into the delicate sympathy shown in the handling, and to trace in the modelling of the lips, the hands, and in the round faces the indefinable tenderness that is the characteristic of Miss Levick's work. One finds it too in the rendering of the angels on the memorial tablet. What is the exact nature of this quality, which more than any other gives distinction to a woman's art, and more than any other quality is at her command, it is difficult to say; certainly it is a quality of the heart. Ruskin, with his dictum that high art was the result of the brain, the hand, and the heart working together, was not quite right perhaps; very excellent work may have been done” by men — stands out indeed amongst remarkable art — which is so scientific as to give no evidence that other than hand and brain were concerned in its creation. The evidence that the heart has not informed a woman's work takes from it all significance as an important work of art, and leaves it feebly a reproduction or an impotent rearrangement of the work of the masters. The word heart in this case, of course, includes anything in art that has passed out of the regions of theory, out of the realm of learnable facts into that realm where all interesting art commences — namely, where it expresses not a view of art, but a view of life; where it expresses the artist's feelings towards life in the same way that an instrument expresses a musician's. Just to remember that his material takes the place in the artist's hand that an instrument takes in a musician's gives us the secret of where art ceases to be imitative and becomes creative; and that is where it ceases to strive for form so much as for expression through form — the one having, where mastery is attained, if only to a degree, become, in extent according to that degree, synonymous with the other. For the sake of extraordinary invention, for the sake of any contribution towards the science which broadens every century the fields of artistic expression, we have raised work contributing thus to an exalted position; but is it not certain that scientific contribution, thoughtful invention, in short, all the many ideas that have contributed to the twistable logic of painting and sculpture, have not come in any one case from a woman, and so are not likely to come from her? And this leaves us, in looking at woman's work, at the mercy, if not of emotion, at least of a possible revelation in it of the finer instincts that are hers.

Left to right: (a) Spring. (b) [Girl with flowers].

Very naturally. Miss Levick has drifted into the portraiture of children; it is this which gives her her chief pleasure, when such opportunity comes to her amongst other commissions. These other commissions have included many things. She is now engaged in making a decoration for a shopfront in Sloane Street; it is the ambition of the proprietor of that shop to make it outwardly the most beautiful in that accidentally beautiful street. In connection with her decorations in the little chapel at Hunstanton she was commissioned to do two windows; and it is surprising that she passed from clay to the designing of coloured glass, keeping the best of her art in this strange transition. A more imaginative phase of her art is seen in the group, Asleep in the Arms of the Slow-swinging Seas; more imaginative we mean in its composition — for imagination is what has entered into the reality of expression in her modelling of the faces— the imagination which is insight — as much as into the more literary motive of this group. The unfortunate limitations of photography prevent an adequate reproduction of this; it will be seen there is in the reproduction a tendency to throw the hand of the woman too much into prominence, to make it too big, and to lose the effect of the Studiously modelled drapery that takes a high quality of design in its folds. This group was bought by the Queen, and, in spite of the faults of reproduction mentioned, its beauty must be obvious in what is apparent here.

Panel in reredos.

The Sea-Urchin is reminiscent of the artist's earlier studies in its scholarly modelling; it is done for the study's sake, and, perhaps because it is the figure of a child, it has in it the same conscientious study that was evident in the Wrestlers, the Hammer-thrower, and the Footballer, works which, teaching her much, proved also how thoroughly she had learnt her craft, and how thoroughly intimate she had made herself with complicated problems of anatomy. The reproduction from the coloured plaster Spring suffers in the same way as the group above referred to; in this case also the camera has failed to reflect in correct proportion the design. Sufficient evidence of the movement contained in the design and of its originality remains, but the best example of the artist's coloured plaster work is the panel with flowers and child. This panel had a particularly refined quality of colour, and in the treatment of the flowers, in the disposition of the child's hair, and in the sensitive face, there is presented the essentials of Miss Levick's art. The simplicity of the modelling in the child's dress gives a pleasant relief to the detailed flowers, though there are to be seen in the surface of this dress some of the not quite completely felt lines that here and there mar slightly the full value of Miss Levick's modelling. She returns to a flower in the tall hollyhock which the fairy kisses in the silver panel, and the dainty fancy here could, it seems to us, have received more the polish of extreme finish, as when one shuts a pretty fancy in a few lines of polished verse. Some of the modelling, especially in the lower part, is scarcely expressive, and this quality of unfinish has not achieved that emphasis which it is the aim to gain when any one part of a design is so left. Returning to the heads of children modelled by Miss Levick in her studio, her studies hint at what a field for work in this direction lies open for her, because they are very few by whom the delicate beauty of children's faces can be carried into a portrait bust, though the beauty is so apparent. Not until one comes to think over it does one realise how scarce it is to find in women indifference to this beauty, and yet how scarce it is to see it retained in their arts.

Left to right: (a) Detail in reredos panel. (b) Sleep.

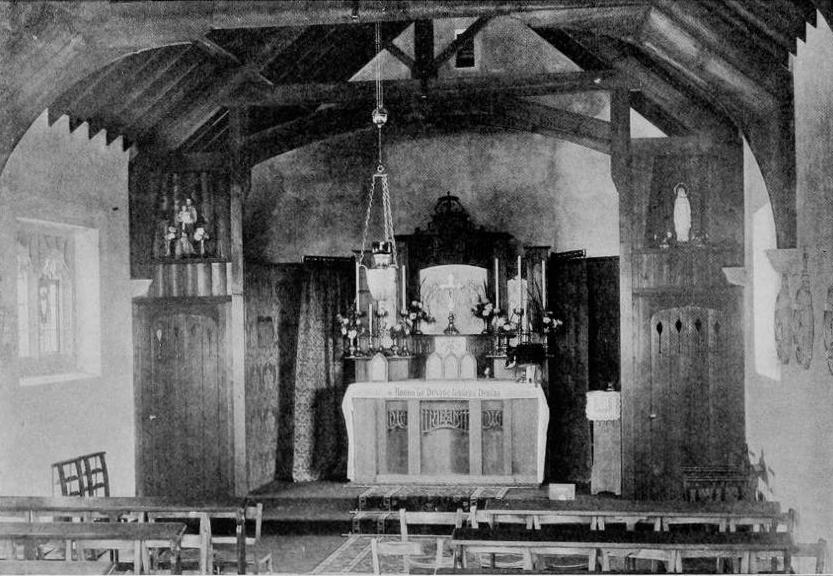

We give an illustration of the chapel at Hunstanton because, if any place was the place for Miss Levick's sculpture, this is it. The the chapel into a beautiful place: a craving to decorate has not outrun the purpose of the building; fitting is it as the environment of the service to which it is consecrated — a village service. Fortunate was the choice of a decorator, for her art has in itself the same elements to simplicity and restraint which give to the little chapel its dignity.

Memorial relief panel.

In everything Miss Levick has done she has given one the impression of having done it more for the pleasure of finding self-expression in it than for the pleasure of competing in sculpture, though she must be taken seriously as entering the competition for distinction amongst our youngest sculptors by the fact of the individual element that enters so largely into her art. The problems that face the sculptor between Hellenic beauty and modernity, between what is classic and what is realistic, what is scholarly and what is romantic, do not affect such work as this, which seems to be sheltered almost in a domestic circle, and to exist, with a reminiscence here and there of things learnt from one source and another, for its own sake only. It may be prevented by this contentment from receiving a very serious consideration; but if one goes deeper, one finds in its unassuming qualities fidelity to its environment, to the conditions that surround the sculptor; and in art what is really of value expresses this. The lack of self-consciousness in Miss Levick's art is not one of the least of its qualities; that it is free from affectation, and that it is concerned with an outlook which is the outlook from the ordinary home, comes to be so by a modification of the laws that give us the tremendous sculpture of a Rodin, representing the larger forces of the modern world — might we not almost say, too, by a modification of the laws which make the heroic sculpture representative of Grecian heroism. The range of Miss Levick's sculpture is within the small circumstances of life; and it is a true saying that art does not rest with the object represented, but with the manner of its representation.

St. Edmund's Chapel, Hunstanton, decorations by Ruby Levick.

It is curious that, although in painting England admits of and even welcomes art which in its intention is narrow and in its expression limited — art which concerns itself, as it were, with the perfecting of gems; hinting delicately at intimate sentiment, or concerned altogether, perhaps, with the presentation of something of the slightest import, or having no message other than that of captivating our sense of pleasure — this does not seem to be the case with sculpture. In this art the minds of artists seem hemmed about with traditions — whether of Hellenic beauty, or of Florentine expressiveness, or of the rebellion that in Rodin's art gives form to imprisoned spirituality. Out of England sculpture is aware of the fact that there can be an art as a flower growing near to all these things, concerned with neither of them — a natural, even a domestic, art, embodying what is quite transient, the movement of a woman in modern costume; an art trivial often in its aims, but not mean even then, because its inspiration has been in triviality, and inspiration even of this kind is more valuable in its contribution to sculpture than are uninspired exercises in the classicism of the Greeks, or insincere pretensions to the emotionalism of a Meunier or of a Rodin. The word big has entered the studios, to complete the ruin of more than one petit-maitre.

The world now has been divided up into gardens; and where the ancients tilled the ground, it is left for us to grow our flowers. And we may not make the past of art art's future. All this bears upon the subject in hand, upon Miss Levick's sculpture, because in her art such conclusions have been arrived at, though, perhaps, unconsciously. By striving in her art for expression to the gentle aspect of life which has appealed to her, even if there may be sometimes hesitation in her technique, her art is surely creating for itself its own atmosphere, and at the same time setting itself free from a cold scholasticism. T. Martin Wood.

Bibliography

Wood, T. Martin “A Decorative Sculptor: Miss Ruby Levick: (Mrs. Gervaise Bailey)”. The Studio 34 (1905): 100-107. Internet Archive. Web. 29 January 2012

Last modified 29 January 2012