This article has been peer-reviewed under the direction of Professors Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge (University of Victoria). It forms part of the Great Expectations Pregnancy Project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Victorians have a reputation for prudery and especially for not discussing pregnant bodies. However, it is not true that they avoided discussions of pregnancy. Rather, they used terms that are not the same as ours, and they often used tactful references that we may fail to recognize. The following list identifies and provides explanations for common nineteenth-century terms related to menstruation, pregnancy, and childbirth. Where possible, examples of Victorian phrasing are provided.

Pregnant

Title page for Chavasse's Advice to a Wife on the Management

of Her Own Health, 10th ed., 1873.

Although pregnant is the most common modern term for expecting a baby, the Victorian press used the word primarily to refer to fullness (of meaning, significance, understanding, etc.). When used to refer to gestation, pregnant was not considered a tactful way of describing a middle- or upper-class white woman; indeed, it rarely appears in Victorian novels in such a context. In commenting on the word's tactless connotation, the Satirist noted on 27 November 1836, "the pregnancy of the Queen of the Belgians is shortly to be announced. How indelicate!" ("Multiple" 381). However, pregnant and pregnancy appear frequently in advice manuals for women, including in the title of Pye Henry Chavasse's Advice to a Wife on the Management of Her Own Health and on the Treatment of Some of the Complaints Incidental to Pregnancy, Labour, and Suckling (10th ed., 1873).

Unpregnant

Unpregnant, a term that has assumed considerable contemporary currency, dates to Shakespeare's Hamlet, where it refers to being unimaginative. The OED traces its meaning of not carrying a fetus to 1772, when N. D. Falck's A Treatise on the Venereal Disease In Three Parts defined "catamenia" as "the monthly discharge from the pudenda in women whilst unpregnant." Unpregnant was current in the UK and US in the nineteenth century.

Caught

In a 15 June 1858 letter to her eldest daughter (Victoria, the Princess Royal) after her marriage in January 1858, Queen Victoria uses the term "caught" to refer to her own first pregnancy in 1840: "Think of me who at that first time, very unreasonable, and perfectly furious as I was to be caught, having to have drawing rooms and levées and made to sit down — and to be stared at and take every sort of precaution" (Fulford 115).

Interesting condition

Variations on this phrase (in an interesting condition, situation, or state) were common ways of tactfully describing a pregnant woman. The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser announced Queen Victoria's first pregnancy on 25 April 1840 by referring to her "interesting situation" ("Queen" 3). So common was this usage that Charles Dickens used it ironically in a 10 August 1848 letter referring to his wife's pregnancy with their eighth child: "Mrs. Dickens being in an uninteresting condition, has besought me to bring her out of London for two months" (Dexter 215). Derived from the Latin inter (between) and esse (be), interesting was commonly used to convey a suspended or incomplete state, as in a cricket game being "in a very interesting condition" ("Cricket" 4) or a missionary commenting that "there are several families in an interesting condition, and I trust they may soon be enabled fully to make a profession of Christ" ("India," 22). The word's suggestion of unknown outcomes implies that interesting was not merely a euphemism but a subtle reference to the various unknowns of pregnancy in an era of relatively high infant and maternal death in childbirth. Other tactful ways of describing pregnancy included in a delicate condition or state and in a state of domestic solicitude.

In the family way

In the family way was a common expression (UK and US) for pregnant, with usage such as eight months, taken, appearance of being, or discovered to be in the family way. It applied equally to married and unmarried women. For example, The Times reported on 29 February 1860 that "a well-dressed young married woman, far advanced in the family way, was charged with systematic robberies" ("Police" 12).

Gone

Less common than in the family way but still in common usage (UK and US) throughout the century, the expression gone (as in six months gone, several months gone, gone with child, gone in the family way, and gone in pregnancy) dates at least to Shakespeare, where it appears in Love's Labour's Lost: "[S]he is gone; she is two months on her way" (V.ii, c. 1595). In 1847, the Lady's Cabinet of Fashion, Music and Romance reported that "upon the coroner's inquest it had been discovered that the woman was six months gone with child" ("Mister Popjoy" 391). The verb to go referred to time spent in gestation, as in "the females of different animals go some a longer, some a shorter time" (Webster, vol. 1, 760).

Lusty

Lusty (UK and US) referred generally to being full of lust but was also used to describe those who were stout or corpulent — and by extension, in colloquial use, to those who were pregnant. As Fanny Kemble wrote in 1863 about slaves on her husband's plantation in Georgia in 1838-39, "I came upon a gang of lusty women, as the phrase is here for women in the family-way" (143).

With child (gone, big, heavy, great)

The expression with child appears in the King James Bible: see Luke 2:5, which refers to "Mary being great with child." In the nineteenth century, with child (UK and US) often appeared with an adjective such as gone, big, heavy, or great. For example, on 28 January 1841, The Times reported on a woman living in a workhouse who was "six months gone with child" ("Her Majesty" 4). On 29 May 1851, the Daily News referred to a "lady big with child" ("Earl" 5). On 13 March 1853, Lloyd's Illustrated Newspaper alluded to a "women heavy with child" ("Sacred" 1). And a poem published in the Cork Examiner on 5 December 1842 alludes to "women great with child" (Macaulay 4). Finally, Noah Webster's 1841 American Dictionary of the English Language includes the terms "bigbellied" (vol. 1, 175) and "great-bellied" (vol. 1, 775).

Teem, teeming, teemful

To teem (UK and US) meant to be fertile, to bring forth young and applied both to animals and women. Sir Walter Scott writes in The Pirate (1821) that "Mrs. Yellowley had a remarkable dream, as is the usual practice of teeming mothers previous to the birth of an illustrious offspring" (347).

Unwell, ceasing to be unwell

Although, as Isabel Davis notes, pregnancy was difficult to confirm in its early stages, Victorian advice manuals identified a missed menstrual period — a woman's ceasing to be unwell — as an important indicator of possible pregnancy. In Thomas Bull's Hints to Mothers (1842), he refers to the expression ceasing to be unwell as "female phraseology" (36). Bull alternates between medical discourse ("that period of the month arrives when she is accustomed to menstruate") and common speech ("when she expects to be unwell, she finds that she is not so") (36). Other, more medical ways of referring to a missed menstrual period were "cessation of the periodical discharge" (Fox 3), "omission of [the] regular monthly return" (Bull 36), "a woman who has missed her month" ("Review," 292), and "cessation of the catamenia" (Wharton 307). Colloquial terms for menstruation included "courses" (Stout 346), "monthlies" (Secret, vol. 1, 154), "periods" (Chavasse, Wife 143), and feeling "poorly," as in the pornographic My Secret Life, where menstrual discharge is referred to as "poorliness" (vol. 3, 103).

Page 36 from Thomas Bull's Hints to Mothers, for the Management of Health During the Period of Pregnancy, and in the Lying-in Room, 1842.

It might seem surprising to us that Victorian women sometimes struggled to discern whether they were in the early stages of pregnancy, but many advice writers pointed out that a mother could conceive while breastfeeding an infant and therefore at a moment when she was not menstruating, with no period to be missed. Women might also get pregnant after their periods had become irregular or stopped entirely in early menopause. Ceasing to be unwell was therefore an acknowledged but not always reliable sign of early pregnancy.

Somewhat confusingly, given that missing a period was referred to as ceasing to be unwell, pregnant women were often described by others and themselves as unwell. Emma Darwin, Charles Darwin's wife, described the early months of her third pregnancy when she "began to be languid and unwell"; her husband also referred to her as "poorly" and "not being well enough to go out at present" (qtd. in Cox). Labour's onset might also be described in terms of illness. In Ellen Wood's Lord Oakburn's Daughters (1864), the landlady says to a pregnant woman, "I hope you don't feel as if you were going to be ill" (13). The servant asks, "Is she ill, ... She looks not unlikely to be" (16), and another character says, "she won't be ill for these two months" (16)that is, she is seven months pregnant. The onset of labour could also be described as being taken unwell, as when the Morning Chronicle commented that Queen Victoria had been "taken unwell and her medical attendants summoned" for the delivery ("Accouchement" 3). So common was the connection between illness and pregnancy that the Satirist exploited it in a 6 December 1840 ditty about Queen Victoria immediately following the Princess Royal's birth:

Next time we'll hope that Vic

More fortunate may be,

And when she's taken sick,

A Prince of WALES we'll see. ["Royal," 383]

Gravid

The adjective gravid, from the Latin gravidus, from gravis (heavy), was a medical term meaning pregnant (UK and US): see Webster vol. 1, 773. It was used, for example, in the title of J. Burns's

Quickening, quick

Quickening (from quick, meaning alive) refers to the fetus's first perceptible movements in the uterus. Unlike our modern division of pregnancy into trimesters, the Victorian stages of pregnancy, as shown in reckoning tables (see "Reckoning tables" below), comprised "the beginning" (before the quickening); "the middle" (the quickening itself, occurring around the fourth month, when a woman and her medical attendant or midwife could be sure she was pregnant); and "the end" (the due date, often calculated from the quickening in cases when the conception date was uncertain). Legally, quick with child meant having conceived, whereas with quick child meant that the fetus had moved (Forbes 30). A woman might know herself to be pregnant (i.e., quick with child) but was not legally considered to be pregnant until she was with quick child.

Plead the belly, belly plea

Under British common law, life began at the quickening (even though inheritance laws acknowledged a legitimate child not yet quick when the father died). Women convicted of capital crimes and condemned to execution could plead the belly (i.e., declare themselves pregnant). If their declaration was confirmed by "a jury of matrons" or, after 1890, a medical man, then execution was postponed until after the birth. In practice, after 1800, such belly pleas (Grose et al.) declined, and after 1848, women were no longer executed if given such a reprieve. The last belly plea to be made at the Old Bailey (the London Central Criminal Court) was in 1880 (Emsley).

From the Juries Act 1890, Section 90 in Louis Horwitz's The Victorian Statutes: The Public Acts of Victoria, Arranged in Alphabetical and Chronological order with notes and Indexes, vol. 4 (Melbourne: Sands and McDougall Limited, 1899): 109.

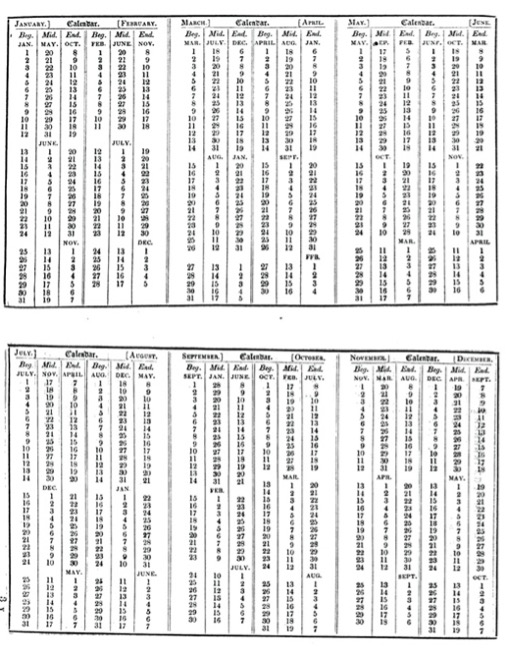

Reckoning, reckoning tables, out in her reckoning

Reckoning, a general term for calculation (of money, duration, etc.), had, from the sixteenth century, also meant calculating a pregnancy's duration, whether for animals or women. In The Book of the Farm (1855), Henry Stephens describes a shepherd who has "attentively observed the tupping [i.e., mating], and marked the reckoning; of every ewe" (155). Reckoning tables were the Victorian equivalents of modern pregnancy calculators, providing an estimated due date based on the date of the pregnancy's "beginning" and of the quickening.

Reckoning table for calculating a pregnant woman's due date, from M. Ryan, A Manual of Midwifery, 52829.

The term "beginning," seen on the lefty in the reckoning table ("beg"), may seem vague to us. For much of the century, however, there was uncertainty about when during the menstrual cycle conception occurred. Whereas Thomas Bull believed conception to take place "a day or two after the last menstrual period," he acknowledged that others were "in the habit of reckoning from the middle" of the cycle (123). In 1891, James Oliver wrote in the Lancet, "it is generally believed that impregnation is more likely to take place immediately after the cessation of menstruation than at any other time" and noted "the majority of authors are agreed [that] we ought to fix the probable date of delivery on the 278th day from the day of cessation of the last menstruation" (715). (Current medical estimates calculate the average due date as 280 days past the first day of a woman's last menstrual period.) Confusion about the timing of women's greatest fertility led some couples to believe that intercourse at mid-cycle was unlikely to cause pregnancy (Brodie 30), whereas we now recognize this part of the cycle as, on average, the most fertile.

Victorian women who did not know the date of their last menstrual period could use a reckoning table to calculate their due date from the quickening. Reckoning from the quickening could be unreliable, however. Although reckoning tables estimated the quickening to take place at four and a half months past "the beginning," Bull noted that out of 70 pregnancies among his patients, the quickening occurred variously from the third to the sixth month (although the majority occurred in the fourth). If a woman had either lost track of her menstrual cycle or perhaps conceived while breastfeeding, she might be put out of her reckoning; as Pye Henry Chavasse wrote, she "does not know how to 'count'" (Advice 155). Colloquially, especially in Scotland, a woman in such confusion was said to have lost her "nickstick," a nickstick being a notched stick on which one might keep a tally of purchases or days ("nick").

Enceinte, enceint, privement enseint

The word enceinte (UK; also enceint US) entered English from French in 1599 and was commonly used as a polite or legal reference to pregnancy until around 1860. An early reference to Queen Victoria's first pregnancy was the headline "The Queen Enceinte" on 27 March 1840 in the Globe (4). Privement enseint (literally, privately pregnant) was a legal term referring to the "beginning" stage of pregnancy before the quickening, when a woman might suspect or discern her pregnancy, but it was not yet medically confirmed or legally recognized.

Abortion, miscarriage, miss

As Shannon Withycombe notes, the terms abortion and miscarriage (colloquially known as a miss; as in W. Somerset Maugham's Liza of Lambeth, 206) were often used interchangeably in the nineteenth century. An example of this interchangeable use occurs in Douglas Fox's The Signs, Disorders and Management of Pregnancy (1834), where conditions such as toothache, stomach spasms, and cramp of the lower limbs are described as possibly leading in pregnant women to "abortion, or miscarriage, if neglected" (57). However, references to causing or procuring an abortion or to criminal abortion signify intentional termination of a pregnancy and appear in newspapers across the century, as in "Threatening Letters" (56), "Country Assizes" (275), and "Shocking Case" (2).

Confinement, confined

Whereas "the common narrative of Victorian pregnancies is that women hid away from [i.e., were confined from] the world for the sake of decency," scholars have shown this narrative to be untrue (see McKnight). Confinement (UK and US) referred not to a period of seclusion during late pregnancy, as has sometimes mistakenly been assumed, but specifically to the condition of being in childbirth ("confinement"). As a 1 July 1850 correspondent wrote in the British Mothers' Magazine, "in my last confinement I suffered most severely for three days" ("Correspondence" 163). Victorians referred to a pregnant woman's anticipated confinement as we would to her due date: as Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle reported on 22 March 1863, a woman charged with concealing the birth of her child claimed that she had not "expect[ed] to be confined till a month later" ("Concealing" 8).

Labour, pangs, travail, take a pain, flooding

As it is today, labour (labor US) was widely used in the nineteenth century as a term to describe the process of birth, from initial onset to fetal and placental delivery. Victorians also referred, as we do, to labour pains (Fox 67) or, as they also termed them, pangs (UK and US): Chavasse refers to pangs of labor (Wife 185), and the OED to pangs of childbirth ("pang"). Victorians also referred to a woman's travail (UK and US), a term borrowed from the French travailler (to labour) and in English use from the thirteenth century. The term appears frequently in the King James Bible to denote childbirth or painful suffering, as in Jeremiah 6:24: "anguish hath taken hold of us, and pain, as of a woman in travail." However, travail was current in the nineteenth century, used both in medical manuals (Tanner refers to "the pains of a woman in travail" [67]) and in fiction (Thomas Hardy writes of "the travail of the sea without and the travail of the woman within" in The Well-Beloved [215]).

Plate 13 from M. Ryan's Manual of Midwifery (1841) "shows the mode of instituting a vaginal examination with the fingers" (534).

Notably, medical texts such as Henry Miller's The Principle and Practice of Obstetrics (1858) refers to the "mechanism of labor" (Miller 328). This view of labour as a mechanical process implied that men (seen in the period as naturally more mechanical than women) were better suited to assisting during childbirth and using obstetrical instruments than were women (Donnison 59).

Medical examination of the cervix during labour was referred to as taking a pain or trying a pain (Chavasse, Advice, 182; Wohl). In this procedure, still performed today, a doctor or midwife inserted a finger or two into the labouring woman's vagina to ascertain the extent of the cervix's dilation and effacement, as well as the position of the fetus. Finally, the extremely dangerous phenomenon of uterine hemorrhage (i.e., uncontrollable bleeding) was referred to as flooding (Fox 75), and women prone to such hemorrhages as flooders ("flooding").

The use of ether and chloroform to alleviate labour pain was introduced by James Young Simpson, a Scot, in 1847 (Edwards 1). Queen Victoria used chloroform for the delivery of her eighth child in April 1853. Some Victorians questioned whether giving pain relief in labour was contrary to God's statement in Genesis 3:14 that "in sorrow thou shalt bring forth children." Writing in 1849 on anaesthesia in childbirth, however, Simpson argued, "if some physicians hold that they feel conscientiously constrained not to relieve the agonies of a woman in childbirth, because it was ordained that she should bring forth in sorrow, then they ought to feel conscientiously constrained on the very same grounds not to use their professional skill and art to prevent man from dying; for at the same time it was decreed that man should be subject to death, — dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return" (11213).

Accouchement, accoucheur

In French, accoucher means to take to one's bed in order to give birth. Borrowed from French, the commonly used Victorian English term accouchement (UK and US) referred to delivery, and accoucheur referred to a person, usually a professional man, who assisted a woman during delivery. As Hilary Marland notes, such men presented themselves, in contrast to midwives, as experts in the medical management of childbirth. Accoucheurs (UK and US) were often employed by middle- or upper-class women, as suggested in a Cleave's Penny Gazette cartoon on 11 July 1840. Leading up to the accouchement of Queen Victoria, a working-class man remarks sardonically that the 'a-coach here' (i.e., accoucheur) anticipates that his wife will "tumble in two about the same time as the K'veen" ("Interesting" 1). Working-class women would have been much more likely to use midwives or lying-in hospitals as opposed to professional accoucheurs, so the cartoon is clearly ironic.

Childbed, childbed linen, death in childbed

Childbed (UK and US) was frequently used in both the medical literature and the press to mean childbirth. Childbed linen referred to the necessary sheets and other coverings that protected the mattress during delivery. Working-class families used sheets and calico (a durable, heavy, inexpensive cotton fabric) that would often be loaned by charitable organizations; for middle-class women, Douglas Fox recommended using leather, oiled silk, or waterproof cloth tied to the bedposts and placed under sheets in order to protect the mattress from becoming "wet or soiled" (70) with amniotic fluid, blood, and/or excrement. Later in the century, rubber sheets were used.

Childbed (UK and US) was also the medical term for what we now call maternal mortality (i.e., death during childbirth). In 1822, Bell's Life in London listed childbed between cancer and consumption in its alphabetical list of "Diseases and Casualties This Year" in London (5). Newspaper announcements commonly cited in childbed as a cause of death. For example, on 1 December 1870, the Australian Journal announced, "Tandy — 13th at Williamstown (in childbed), aged 19, Jane, wife of G.P. Tandy" ("Deaths" 63). Childbed fever was a common term for puerperal fever, now known as septicemia. (See Marland.)

Delivered of

Plate 15 from M. Ryan's Manual of Midwifery (1841) shows birth with the woman on her back (identified as "the position preferred in most parts of Europe and America") and on her left side ("the British obstetric position") (534). The woman in the image is wearing stockings, a common practice intended to keep her feet warm during childbirth. In figure 3, there appears to be a bolster between the woman's knees to keep them apart.

Whereas we now refer to a midwife or doctor delivering a baby, Victorians spoke of the pregnant woman being delivered of a child (UK and US). The Oxford English Dictionary notes the connection between the idea of delivery and the "freeing [of] a woman from a burden" ("Delivery"). For example, in the "Births, Marriages, and Deaths" column, the World of Fashion and Continental Feuilletons announced that a woman had been "safely delivered of" triplets (284). The idea of deliverance from danger is apparent in the traditional Anglican service for "The Thanksgiving of Woman after Child-Birth," commonly called The Churching of Women (see The Book of Common Prayer). The service urges the mother to thank God "forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God of his goodness to give you safe deliverance, and hath preserved you in the great danger of child-birth" ("Thanksgiving").

In midwifery books and medical manuals, the term undelivered was used to describe the state of a pregnant woman, usually in labour, for whom treatment options had to be assessed in light of the risks to both mother and fetus: "little can be done by way of treatment so long as the patient remains undelivered" (Meadows 251).

Brought to bed of

This phrase is synonymous with delivered of and appears commonly throughout the nineteenth century in both religious and colloquial contexts. On 1 July 1805, the Lady's Monthly Museum featured a play in which a man remarks, "soon after our marriage, my wife was brought to bed of a son" (E. F. 31). So common was this phrase that it could be used metaphorically for literary creation: a parliamentarian could be "brought to bed of his annual address" (Ivan 154), or Benjamin Disraeli described as "brought to bed of Coningsby," his 1844 novel (Millar 159).

Lying-in, lying-in period, monthly nurse, general practitioner, lying-in hospital

Lying-in (UK and US) functioned as both a noun (her lying-in) and an adjective (lying-in bed, room, ward, hospital, or charity). This extremely common and non-euphemistic term, dating to the fifteenth century, refers to childbirth and the mother's subsequent recovery. In the nineteenth century, most women gave birth in their homes. Working-class women were normally attended by female family members, neighbours, and possibly a midwife; middle-class women were attended by a midwife or doctor (possibly a general practitioner, so called because they combined the duties of a surgeon-apothecary with midwifery: see Donnison 55); and upper-middle-class and aristocratic women by a professional accoucheur, normally a man.

During the lying-in period (of roughly ten days following childbirth), women rested and recovered in seclusion with women attendants, possibly including a monthly nurse, whose professional duty was to assist with postpartum recovery. Recovering women were not expected to do housework or childcare. In middle-class and aristocratic homes, servants and nannies would do this work; in working-class homes, female relatives and neighbours did it. Pressed for space, a new working-class mother might find herself "sharing a bed with extended female kin" (Holmes 40).

Lying-in hospitals (later known as maternity hospitals) were established to provide a place to give birth and recover to low-income women who could not otherwise afford assistance or privacy in childbirth. Infant and maternal mortality rates were higher at lying-in hospitals than for home births. As Hilary Marland observes, such institutions were subject to outbreaks of puerperal fever — that is, sepsis caused by lack of sterilization in an era before germ theory was well understood. Historians associate the establishment of lying-in hospitals with the gradual medicalization of childbirth.

Little stranger

A fond reference to an as-yet-unborn or newborn child, this term appears widely in literary references. Expectant mothers, female friends, and relatives often embroidered the phrase on gift items intended for newborns. Pincushions bearing phrases such as bless the or welcome little stranger were common gifts for a layette (i.e., a collection of items, including clothing, diapers, caps, and blankets, intended for the newborn's first weeks of life). Such items formed a potential bridge between pregnancy and childbirth, being created before labour but addressed to the little stranger whose arrival might follow that labourwhich might equally be the occasion of the mother's and/or child's death in a period of relatively high maternal and infant mortality.

"May HE whose Cradle / Was a Manger / Bless and Protect / The Little Stranger," handmade layette pincushion c. 1862. Courtesy of the V&A Museum.

Parsley Bed

Dating to the seventeenth century, the parsley bed was a common English euphemism to explain to children where babies came from (akin to the European legend of the stork delivering babies). In a 1900 stage version of The Sleeping Beauty, the fairies discuss the king and queen's infertility and plan to deliver them a baby: "Suppose a little child we hide away, / In parsley bed, for them to find to-day" (Wood). By extension, the parsley bed signified sexual knowledge: as an article in Bell's Life in London expressed on 25 August 1833, "We cannot explain to Julia the origin of the parsley bed. No doubt if she applies to some of her matronly friends they will give her the requisite information" ("To correspondents" 2). It could also refer to a woman's genitals and to sexual activity. To take a turn among the parsley meant to have sex (Farmer & Henley 5: 141).

Slang terms

While nineteenth-century slang dictionaries provide a lexicon of pregnancy terms, it is sometimes difficult to find examples of their usage. Therefore, the following list draws heavily on such dictionaries and provides terms in context where we have been able to find them.

The word knap (which meant "to steal, receive, accept, or endure" [Farmer & Henley, Dictionary, 255]) was used for pregnancy (knapped the kid, Grose et al.). By extension, one could say of a pregnant woman, Mr. Knap's been there (Farmer & Henry, Dictionary, 255). As it is today, kid was Victorian slang for child; hence, kidded (Farmer & Henley, Dictionary, 252) or having a kid in the basket (Farmer & Henley, vol. 1, 139) meant pregnant. By extension, basket making was slang for sexual intercourse (Farmer & Henley 1: 139). Still in use today, knocked up was American slang for pregnant during the era ("knock"). To sprain one's ankle or toe or to break a leg above the knee were all slang expressions for getting pregnant out of wedlock. Famously, dancer Marie Taglioni declared a "mal aux genoux" (i.e., a knee injury) in 1835 when she was pregnant in order to avoid going onstage without revealing her pregnancy. Later, she happily identified her little girl as her "mal aux genoux" (Walsh 590). A pregnant woman could be described as having a belly full (Farmer & Henley I: 173) or being belly up (Barrre I: 105). Metaphorically, she was termed a bay window (Farmer & Henley I: 146) because her pregnant belly protruded like a curved bay window. Lastly, pregnant women were described as being in the pudding club (Barrre II: 149), possibly because of pudding's colloquial association with stoutness but perhaps also because of its association with sex and the penis ("pudding").

Bibliography

"Accouchement of Her Majesty, and Birth of a Princess Royal," Morning Chronicle (23 November 1840): 3.

Barrre, Albert, and Charles Godfrey Leland. A Dictionary of Slang, Jargon & Cant Embracing English, American, and Anglo-Indian Slang, Pidgin English, Tinkers' Jargon and Other Irregular Phraseology. Vol. 1. Ballantyne, 1889.

_____. A Dictionary of Slang, Jargon & Cant Embracing English, American, and Anglo-Indian Slang, Pidgin English, Gypsies' Jargon and Other Irregular Phraseology. Vol. 2. London: George Bell & Sons, 1897.

"Births, Marriages, and Deaths," World of Fashion and Continental Feuilletons (1 December 1842): 284.

Brodie, Janet Farrell. Contraception and Abortion in 19th-Century America. Ithaca and London: Cornell UP, 1994.

Bull, Thomas. Hints to Mothers, for the Management of Health During the Period of Pregnancy, and in the Lying-in Room. New York: Wiley & Putnam, 1842.

Burns, John. The Anatomy of the Gravid Uterus, with Practical Inferences Relative to Pregnancy and Labour. Glasgow: Glasgow UP, 1799.

Chavasse, Pye Henry. Advice to a Wife on the Management of Her Own Health. 10th ed. London: J. & A. Churchill, 1873.

_____. Wife and Mother; or, Information for Every Woman Adapted from the Writings of Pye Henry Chavasse. Philadelphia: H.J. Smith & Co., 1888.

"Concealing the Birth of a Child," Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle (22 March 1863): 8.

"Confinement," Oxford English Dictionary.

"Country Assizes," John Bull (13 August 1831): 275.

"Correspondence," British Mothers' Magazine (1 July 1850): 163.

Cox, Jessica. Confinement: The Hidden History of Maternal Bodies in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Stroud: The History Press, 2023 (forthcoming).

C., W., "Political Pleasantries," Picture Politics (17 November 1894): 2.

"Cricket," Gloucester Citizen (30 June 1883): 4.

"Deaths," Australian Journal, (1 December 1870): 63.

"Delivered," Oxford English Dictionary.

Dexter, Walter, ed. The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1847-1857. Nonsuch, 1938.

"Diseases and Casualties This Year," Bell's Life in London . 29 December 1822: 5.

Donnison, Jean. Midwives and Medical Men: A History of Inter-professional Rivalries and Women's Rights. Routledge, 1988. Taylor & Francis Online.

E. F. "Indiscretions," Lady's Monthly Museum. 1 July 1805: 31.

"Earl of Lincoln's Divorce Bill," Daily News. 29 May 1851: 5.

Edwards, M.L., and A.D. Jackson. "The Historical Development of Obstetric Anesthesia and Its Contributions to Perinatology." American Journal of Perinatology 34.3 (February 2017): 211-16.

Emsley, Clive, et al. "Crime and Justice: Punishment Sentences at the Old Bailey," Old Bailey Proceedings Online.

Farmer, John Stephen, and William Ernest Henley. Slang and its Analogues Past and Present. Vol. 1. London: n.pub., 1890.

---. Slang and its Analogues Past and Present. Vol. 5. London: Harrison & Sons, 1902.

Farmer, John Stephen, and William Ernest Henley, A Dictionary of Slang Colloquial English: Abridged from the Seven-Volume Work, Entitled Slang and Its Analogues. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1912.

"Flooding." Oxford English Dictionary.

Forbes, Thomas R. "A Jury of Matrons," Medical History 32.1 (1 January 1988): 23-33.

Fox, Douglas. The Signs, Disorders and Management of Pregnancy. 1834.

Fulford, Roger, ed. Dearest Child: Letters between Queen Victoria and the Princess Royal 1858-1861. London: Evans Brothers, 1964.

Grose, Francis, et al. Lexicon Balatronicum: A Dictionary of Buckish Slang, University Wit, and Pickpocket Eloquence. 1811.

Hardy, Thomas. The Well-Beloved. 1892. New York: Harper, 1897.

"Her Majesty, in the Speech from the Throne," The Times (28 January 1841): 4.

Holmes, Vicky. In Bed with the Victorians: The Life-Cycle of Working-Class Marriage. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Horwitz, Louis. The Victorian Statutes: The Public Acts of Victoria, Arranged in Alphabetical and Chronological order with Notes and Indexes, vol. 4, Melbourne: Sands and McDougall Limited, 1899.

"In an Interesting Condition," Cleave's Penny Gazette (11 July 1840): 1.

"India. Dehra Mission. A Fortnight in Rohilcund. Journal of Rev. John S. Woodside. Home and Foreign Missionary Record for the Free Church of Scotland (1 February 1860): 21-24.

Ivan, "Parliament, Press & Platform," Liberty Review (8 September 1894): 154.

Kemble, Frances Anne. Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838-1839. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1863.

King James Bible.

"To Knock Up," Oxford English Dictionary.

Macaulay, T.B. "Porsena's Invasion of Rome," Cork Examiner. 5 December 1842: 4.

Maugham, W. Somerset. Liza of Lambeth. 1897. New York: George H. Duran, 1921.

Meadows, Alfred. Manual of Midwifery. London: Henry Renshaw, 1862.

Millar, Mary S. Disraeli's Disciple: The Scandalous Life of George Smythe. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2006.

"Mister Popjoy," Lady's Cabinet of Fashion, Music and Romance. 1 December 1847: 391.

"Multiple News Items," Satirist, and the Censor of the Time. 27 November 1836: 381.

My Secret Life. Amsterdam, n.pub., 1888.

"Nick," Scottish National Dictionary (1700). Dictionaries of the Scots Language.

Oliver, James. "The Duration of Pregnancy, with Anomalous Cases in the Human Female." Lancet 2 (1891): 714-16.

"Our Sacred British Oak," Lloyd's Illustrated Newspaper. 13 March 1853: 1.

"Police. Worship-Street," The Times. 29 February 1860: 12.

"Pudding,"Oxford English Dictionary.

"The Queen," Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser. 25 April 1840: 3.

"The Queen Enceinte." Globe . 27 March 1840: 4.

"Review of Medical Evidence Relative to the duration of Human Pregnancy, as Given in the Gardner Peerage Cause, before the Committee for Privileges of the House of Lords in 1825, by Robert Lyall, Burgess & Hill, 1826." Lancet. 3 June 1826: 289-300.

"Royal Bulletins Extraordinary." Satirist. 6 December 1840: 383.

Ryan, M. A Manual of Midwifery, and Diseases of Women and Children. 4th ed. London: n.pub., 1841.

Scott, Sir Walter. The Pirate. The Novels of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. with All His Introductions and Notes. Vol. 3. Edinburgh: Adams and Charles Black, 1858.

"Shocking Case." Bell's Life in London. 12 September 1858: 2.

Simpson, J.Y. Anaesthesia, or the Employment of Chloroform and Ether in Surgery, Midwifery, etc. Philadelphia: Lindsay & Blakiston, 1849.

Stephens, Henry. The Book of the Farm. Vol.2, New York: C.M. Saxton, 1855.

Stout, Henry Rice. Our Family Physician: A Thoroughly Reliable Guide to the Detection and Treatment of All Diseases that Can Be Either Checked in Their Career or Treated Entirely by an Intelligent Person, without the Aid of a Physician. Boston: George M. Smith, 1885.

Tanner, Terence Hawkes. Signs and Diseases of Pregnancy. Philadelphia: Henry C. Lea, 1868.

"The Thanksgiving of Woman after Child-Birth," The Book of Common Prayer.

"Threatening Letters," La Belle Assemble . 1 February 1812: 56.

"To correspondents" Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. 25 August 1833: 2.

Walsh, William Shepard, Handy-book of Literary Curiosities. J.B. Lippincott, 1893.

Webster, Noah. An American Dictionary of the English Language. 2 vols. New Haven: n.pub., 1841.

Wharton, Francis, and Moreton Still. A Treatise on Medical Jurisprudence. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Kay & Brother, 1860.

Wohl, Anthony S. The Victorian Family: Structures and Stresses. Taylor & Francis, 2016.

Wood, Mrs. Henry. Lord Oakburn's Daughters. 3 vols. London: Bradbury & Evans, 1864.

Wood, J. Hickory, and Arthur Collins. The Sleeping Beauty and the Beast. London: J. Miles, 1900.

Created 2 May 2023