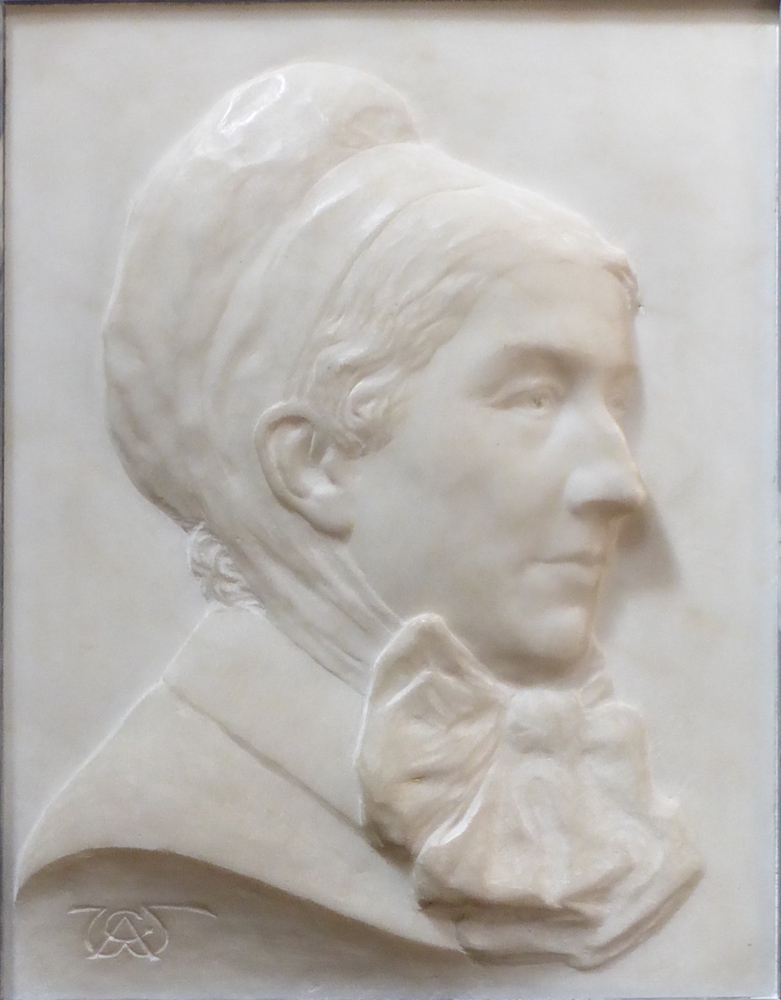

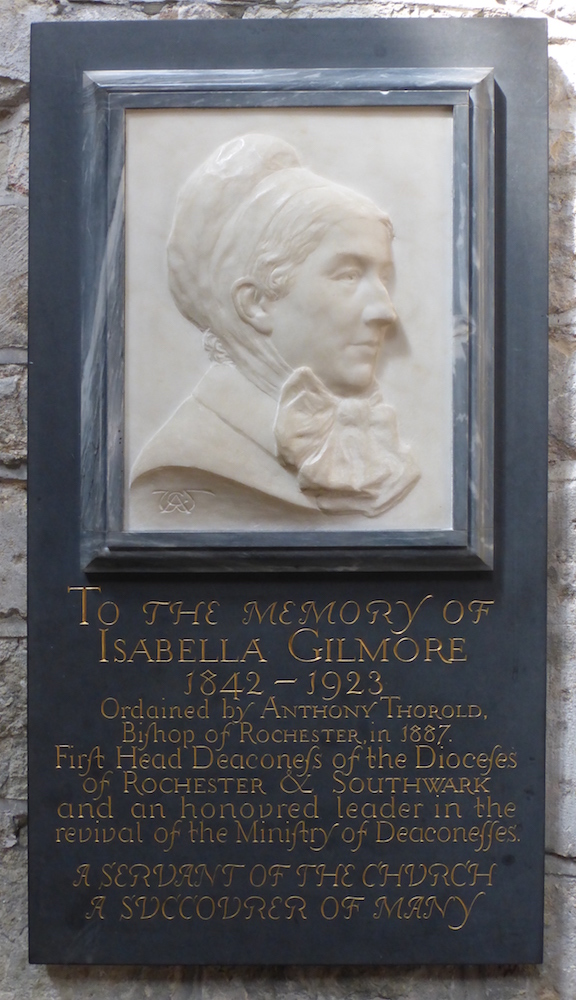

Marble relief of Deaconess Isabella Gilmore by A. G. Walker in Southwark Cathedral. See whole plaque below right. [Click on the thumbnail for larger image and more information about the work.]

Despite family opposition, Isabella Gilmore, née Morris (1842–1923), became a trained nurse and then a Church of England deaconess after having been widowed in early middle age. She is of particular interest as a pioneering churchwoman, and also as one of the sisters of the author and designer, William Morris.

From Issy Morris to Deaconess Gilmore

Isabella Gilmore was born on 17 July 1842 when the Morris family lived at Woodford Hall, Essex: she was the eighth of the ten children of William Morris senior (1797–1847) and his wife Emma (1805–1894). "Issy," as she was familiarly known, was not the only member of the family to have religious leanings. One of her sisters, Emma, married a former curate of Walthamstow, and another, Henrietta, was converted to Catholicism in about 1870.

After being educated at home by a governess, Isabella attended a private school in Brighton and a finishing school in Clifton (an area of Bristol), and married Lieutenant Arthur Hamilton Gilmore of the Royal Navy in 1860. The marriage was childless and Gilmore, who was ten years older than she was, died in 1882 when they were living in Lyme Regis. After that Gilmore took up nursing at Guy's Hospital. In 1884, on the death of her brother Thomas, she also took his large family under her wing — the youngest child being as yet only two years old. Then in 1886 the hospital matron recommended her to Bishop Thorold of Rochester "as a suitable person to found a deaconess order in his diocese" (Martin). Defying her family, and after much hesitation (see Robinson 6-8 for her account of this difficult process), she felt called to accept this new position, for which indeed she proved eminently suited.

Apart from her duties in the church itself, the new deaconess also had to "address meetings throughout the diocese, explaining the objects of the Institution and thus recruiting Associates" (Grierson 69). By 1906, forty-five other women had been ordained. Gilmore "set great store on the fact that in the early Church Deaconesses were ordained and had a definite and distinctive status in the Church's ministry" (Grierson 209). Her idea was to make the parish itself, rather than a sisterhood, the focus of the deaconess's life. To that end the recruits were taught a variety of skills, from book-keeping to nursing. The need to give such training to women working amongst the London poor brought her into contact with another strong-minded and capable philanthropist with similar aims, but operating on her own account — Octavia Hill. The pair were listed in the Times as the two "readers" on this subject at the Church Congress of 1892 ("Ecclesiastical Intelligence"). Gilmore's recruits did not wear habits, but, working under the Bishop as what might now be called an outreach arm of the church, they were distinguished from other philanthropists by wearing uniforms of dark clothes.

Whole memorial, showing Ninian Comper's plaque

This mode of operating was not only demanding, in a large and what was then a very poor area south of the Thames; it had certain drawbacks too. The women lacked the support as well as the familiar habit of a religious sisterhood, and there was some general uncertainty about their roles, both in the church and in the community (see Mangion 78). However, as Mary Martin says, their independent functioning within the church hierarchy seems to have marked a stage in the "eventual admission of women to the Anglican priesthood in November 1992." Moreover, Martin adds, Gilmore's "insistence on rigorous standards in training, and on the independent status of ordained deaconesses, who were paid (her own services were given free), had important implications for the professionalization of women's work from c.1890."

Yet the institution that Gilmore promoted in the church, through her organisational abilities, her reports, her pamphlet on "Deaconesses: Their Qualifications and Status" (revised in 1908) and, last but not least, her untiring example, was not just a stepping-stone to other roles. Today, deacons are still an important part of the church hierarchy in most denominations, and in fact the Church of England has evinced a "renewed appreciation of the order's ancient character and function," with the result that there has been "a growth in the number of permanent or distinctive deacons in the diocese" (as against deacons who are moving on into the priesthood; see "Distinctive and Transitional Diaconate").

Gilmore died at her home in Dorset on 15 March 1923, and was buried beside her husband in Lyme Regis. There was a memorial service at Lambeth parish church, with an address from the Archbishop of Canterbury; and a memorial fund produced enough money to pay for the simple but very beautiful portrait in Southwark Cathedral, with some left over to provide bursaries for deaconesses.

Deaconess Gilmore and William Morris

Although Gilmore achieved so much in her own right, part of her appeal for us inevitably lies in her relationship with her more famous brother. Morris was not one of the family members who opposed her decision to become a deaconess (see Sharp 33). On the contrary, he was supportive. Martin notes that Gilmore put much thought into decorating the houses in Clapham used for training new deaconesses. In fact it was Morris himself who decorated her rooms and the chapel in the first house on Park Hill where Gilmore was ordained in 1887 (see Sharp 23). A few years later, in 1891, the deaconess centre moved to a larger house at North Side (so-called because it is on the north side of Clapham Common). By now, her mother had accepted her new way of life, and, with the money she inherited from her in 1894, Gilmore was able to add a chapel to the house. We have her own first-hand account of her meeting about this with Morris's friend, the architect Philip Webb:

I said, "I want something perfectly simple, I want the green of a field and a great big silver cross." "I see," he said; "not a miniature parish church nor a cathedral." He told me I had given him a difficult job; he would think it all out and come again.

Before long he came and said we had better make a good job of the side of the house, which was very bad. So the large dairy, dark scullery, staircase, and conservatory were all to go and be rebuilt. He sent me the plans, and I then offered my chapel to Bishop Talbot, who had just come. We began to build in the spring of 1896. That was a sad year for me. My dear brother, William Morris, passed away in the autumn, and there were more family losses. I had a serious attack of pneumonia, and there were other troubles; things had become difficult in many ways, but God does not allow us to live always in sunshine.

The building went on all the winter — twenty thousand bricks went into the chapel and many loads of timber. About fifty men worked there all that time. The changes downstairs were very nice.

Early in 1897 all was finished. We had a grand opening and the chapel was dedicated. [qtd. in Robinson 24].

Frank Sharp describes the chapel as a simple one "in an arts and crafts style with a steep roof supported by oak beams" (36). Plain it might have been, but with furniture designed by Webb as well, a cross by artist and silversmith Robert Sidney Catterson-Smith (1853-1938), and an altar-cloth embroidered by May Morris, it must have looked beautiful. Later, Sharp also tells us that Gilmore had the Associate's card printed at the Kelmscott Press, and was very proud of it, and that she had a "close relationship" with both Jenny and May Morris (36). London estate agents' illustrated listings reveal that the Gilmore House chapel is still there, but has been converted as part of the living space of an elegant flat. Only a very striking stained glass window, added in 1911-13 by the Morris firm (see Cherry and Pevsner 386), show that it once served a religious purpose .

In addition to Morris's involvement with the Clapham houses, there was another, more fundamental, link between the two siblings' endeavours: they were both deeply concerned about social inequality. No brief account can do justice to all Gilmore's efforts on behalf of the poor in that part of London. It was not just a matter of providing soup-kitchens and the like, although that was done too. Martin explains that "[w]hile recording that the question of relief was extremely difficult, she established many heavily subsidized forms of philanthropic organization, such as the provision of clothing for small loans, provident clubs, an industrial society, and girls' preventive home (founded in 1893)." Morris is said to have remarked to his sister once, "I preach socialism, you practise it" (qtd. in Robinson 37, Grierson 95, and also in Martin).

Note: In the Roman Catholic church, the deacon is seen to embody "in a particular way, the 'diakonia' of service to those in need which ... is a fundamental characteristic of the life of the Church" ("What does it mean to be a deacon?").

Related Material

Bibliography

Cherry, Bridget, and Nikolaus Pevsner. London II: South. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002.

"Distinctive and Transitional Diaconate." Diocese of London. Web. 9 August 2018.

"Ecclesiastical Intelligence." Times. 30 July 1892: 9. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 9 August 2018.

Grierson, Janet. Isabella Gilmore: Sister to William Morris. London: SPCK (Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge), 1962 (see Chapter 11 on the Philip Webb chapel).

Mangion, Carmen M. Women, Gender and Religious Cultures in Britain, 1800-1940. Ed. Sue Morgan. Pbk ed. London: Routledge, 2010. 72-93.

Martin, Mary Clare. "Gilmore [née Morris], Isabella (1842–1923), philanthropist and Church of England deaconess." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 9 August 2018. (This long entry was the main source of factual information here.)

Robinson, Deaconess Elizabeth. Deaconess Gilmore: Memories Collected by Deaconess Elizabeth Robinson. London: SPCK, 1924. Anglican History. Web. 9 August 2018.

Sharp, Frank C. "Isabella Morris Gilmore." William Morris Society. Find at

"What does It Mean to Be a Deacon?" Diocese of Westminster. Web. 9 August 2018.

Created 9 August 2018