HORNE, in his Rambles by Rivers, published in 1847, incidentally mentions the river Cherwell, and dismisses the subject in a few lines concluding with the remark “It turns several mills but is not navigable.” This is true enough, but the purpose of the present paper is to show, that any one who cares to follow the windings of the stream, either on foot, or still better in a canoe, will be amply rewarded by glimpses of homely but beautiful English scenery, and the contemplation of places which call up recollections of interesting historical events. The Oxford canal, which follows the Cherwell valley for many miles, is often utilized by boating-men who like to penetrate beyond the conventional highway of the Thames, and the characters in Mr. Black’s novel The Strange Adventures of a House-Boat are made to continue their voyage above Oxford by way of the canal, which in one place is identical with the river. As the Great Western railway also follows the valley for about thirty miles, the locality is easily accessible; but the villages all have an old-world look, their popu lation is generally sparse, and visitors are extremely rare, so that the characteristics of holiday places are conspicuous by their absence.

Dr. Faber has written a charming poem on the Cherwell, of which the following are the opening lines:

Sweet inland Brook! which at all hours,

Imprisoned in a belt of flowers,

Art drawing without song or sound

Thy salient springs, for Oxford bound

Was ever lapse so calm as thine,

Or water meadows half so green?

Or weeping weeds so long to twine

With threads of crystal stream between?

and the same gifted author has some beautiful stanzas on the Cherwell water-lily.

It should be noted that those who wish to explore the Cherwell by boat cannot hope to get much beyond the village of Cropredy, a few miles above Banbury, as the channel there becomes very narrow, and the canal leaves the valley.

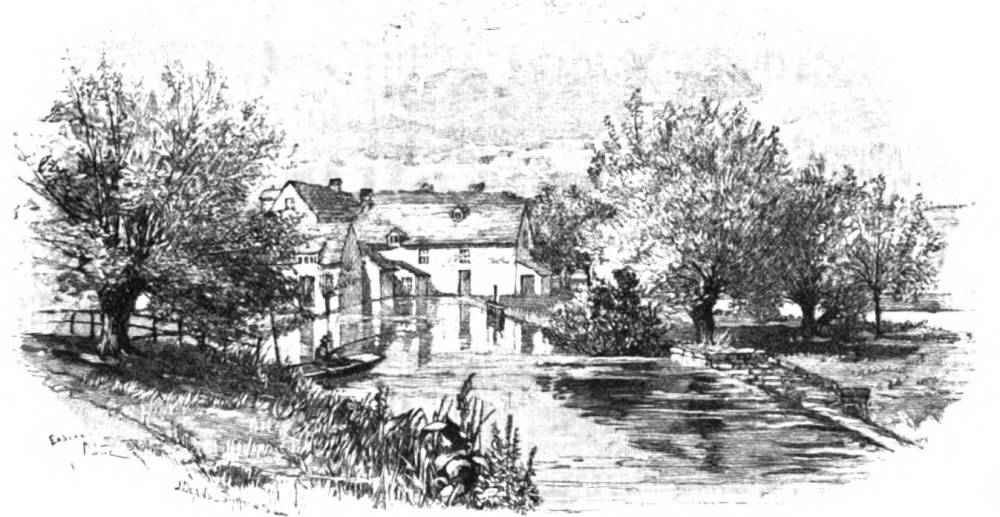

Islip Mill, from below.

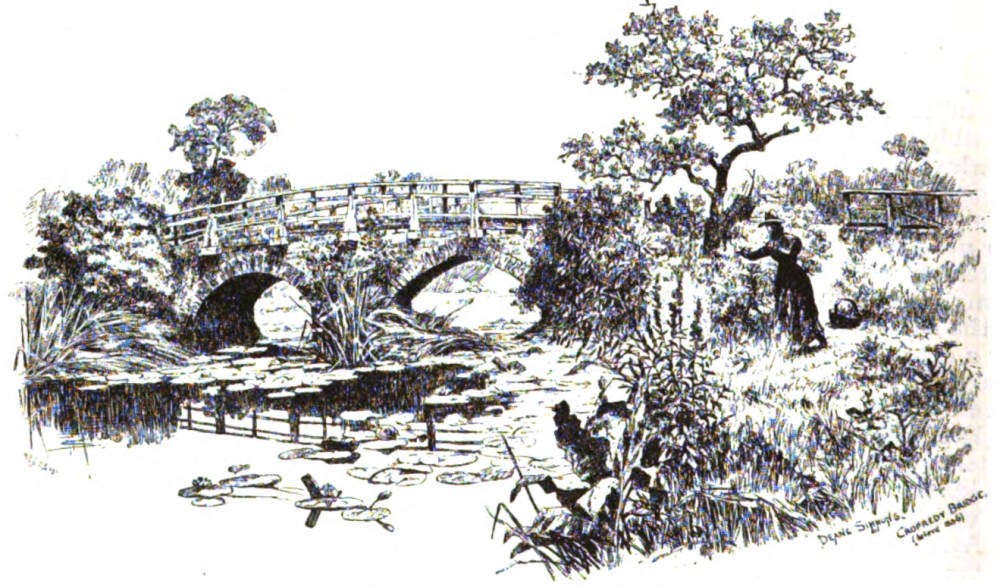

The stream has its source about a mile from the village of Charwelton, five miles from Daventry, in Northamptonshire, commencing with a spring which rises in the cellar of a farm-house. In the village is an ancient foot-bridge which is now only useful in times of flood, as the water is taken under the road by a culvert. Two miles lower down the brook has sufficiently expanded to turn a mill, and increasing in volume by means of tributaries flowing through Eydon on the left, and Chipping Warden on the right bank, by the time Edgcott is reached the river is a formidable obstacle to a hunting man. Egrecott is the last parish in North Hamptonshire intersected by the Cherwell, and the neighbourhood is very interesting. Near here, on the north bank of the river, is the supposed site of the Roman station Brinavis, covering about forty acres, on which have been found many old foundations, and numerous Roman coins and pottery, the place in its way being a small Silchester without the surrounding walls; the modern name of the locality is “The Black Grounds” from the discolouration of the soil. On the opposite side of the stream is Danesmoor, which is said by tradition to be the site of a battle between the Danes and the Saxons; and in the year 1469, when an insurrection against Edward the Fourth broke out in the North of England, the rebels on their way to London, under the nominal command of Robin of Redesdale, met on this same Danesmoor the royal forces, chiefly consisting of Welshmen, under the Earl of Pembroke. A sanguinary conflict took place, in which the latter were defeated, their gallant old chief, with nine other leaders, being afterwards cruelly beheaded in the neighbouring town of Banbury. Edgecote, sometimes spelt Edgcott, has an old church with some interesting monuments to the Chancy family, which, unlike many similar memorials in the district, escaped mutilation during the great Civil War of the seventeenth century. King Charles the First is said to have slept at Edgecote House on October 22, 1642, the night before the battle of Edgehill, but the present mansion is devoid of interest. The Cherwell now enters Oxford shire and reaches Cropredy, one of the most interesting of villages, and associated particularly with the Battle of Cropredy Bridge, fought June 29, 1644. With the knowledge of modern military science and appliances, it is difficult to imagine how so small a stream as the one under notice, could have been a sufficient obstacle to influence the strategy of opposing armies; but there were no pontoon bridges in the Cromwellian period, and the Cherwell is too treacherous and muddy to be passable by armed forces except at paved fords. Thus the old narrow bridge became an important point when the King was marching along one side of the river, and Waller, anxious to intercept him, advanced along the other, both coming from the direction of Banbury.

Charles sent a party to hold Cropredy bridge, which was the only means of com munication between the two armies, except a ford at Slate Mill, a mile below, over which 1,000 of Waller' shorse crossed, the rest of his army forcing the bridge. A battle ensued in the adjoining fields, in which both sides exhibited some skilful maneuvres; the King, however, was most successful, as Waller's forces had to retreat across the bridge, leaving much of their artillery behind them. The King afterwards attempted to gain possession both of the bridge and the ford, but the former was very stubbornly contested; and night coming on found the opposing forces drawn up facing each other, the Royal army near the ford, and Waller at the foot of the opposite hill. Here they remained the whole of Sunday, on the evening of which day the King heard that a fresh body of the Parliamentarians, 4,500 strong, was advancing towards the scene of action; he, therefore, on Monday drew off his forces in full view of Waller, who made no effort of pursuit; in fact he had six hundred men killed and seven hundred taken prisoners. Clarendon says that his defeat “broke the heart of his army.” The old bridge contemporary with the conflict was repaired in 1691, which date it bears, and remained almost untouched until 1886, when the requirements of the neighbourhood induced the authorities to widen the structure.

Cropready Bridge (before 1886).

Although plenty of similar stone to that existing is readily to be found in the neighbourhood, the new work was carried out in blue brick, completely destroying the picturesque character of the southern side of the bridge. The Vicar of the parish, to his great honour, did all that was possible by appeals to the “Society for the Preservation of Ancient Monuments” and otherwise to prevent this act of vandalism, but to no purpose. Relics of the battle exist in the villages up and down the valley, many of the inhabitants having cannon-balls, broken swords, buttons, and rusted weapons in their possession which have been found at various times. In the vicarage is carefully preserved a complete set of Cromwellian armour, with a broken rapier and poignard. The bodies of the slain were probably buried where they fell, as the only record of any such burials preserved in the church is of two or three soldiers who died of their wounds a few days after the battle. The churchyard is full of memorials, one dating as far back as 1631; they are all made of the brown stone of the district, and many are of quaint and excellent design; the following is the inscription on one still in good preservation, “Here is interr'd the Body of Lieutenant Samuel King a Loyall Subject & Souldier faithfull to his late Majesty King Charles the First Obijt March 7 1658 Ætatis Suæ Anno 44. " This stone must assuredly have been erected after the Restoration. Cropredy is justly proud of its church, which is close to the river, and dates from about 1320; the whole edifice is full of interest, with its priest ' s room over the vestry, the very ancient iron - bound parish chest, the monuments showing the mutilations of the Parliamentary forces, the pre Reformation brass eagle lectern, a mediæval fresco, and some very beautiful modern stained glass. There is a huge pendulum from the church clock, which swings to and fro in front of the west window — quite an unusual feature. A pious benefactor, in the year 1572, bequeathed funds to pay for the ringing of a bell in Cropredy church at 6 A. M., at noon, and the curfew at 8 P. M.; the custom is still maintained, but as there is a good striking clock it would seem that the money, which amounts to £, 28 per annum, might be expended in a more profitable manner. Cropredy Cross has dwindled down to the hollowed base in which the first stone of the shaft reposes unfixed; the children of the village call it the “Cup and Saacer,” and the bigger boys, as a test of strength, carry the loose stone to the nearest hedge and back again.

A brief glimpse of the old Manor House, with a part of the moat still remaining, brings us to the mill, which is painfully modern after what has been seen above. Down below the meadows are deliciously green and fresh, and Williamscote House, called by the local people Wilscote, is beautifully placed on the left bank; many remains of the battle have been found in the grounds, and the old house must have suffered severely, as Slate Mill Ford is immediately opposite. From this point to Banbury the river winds about the meadows in eccentric fashion; turning Grimsbury Mill on its way, and furnishing the intake for the water supply of the “Town of Cakes.” Mr. Black, in his novel before referred to, remarks of Banbury that he “found it rather a featureless and empty little place,” and “Banbury did not interest us much.” As seen from the river or canal the town is certainly far from picturesque, but for all that few small country towns can boast of so many really interesting and historical features. Comparatively empty on six days of the week, on Thursdays when the market is being held Banbury is full of life, and being the centre of a vast and, in better days, thriving, agricultural community, much business is transacted.

The Courtyard, Reindeer Inn, Banbury.

From the tourist’s point of view the old buildings, mostly of the seventeenth century, are very remarkable; chief of these is the Reindeer Inn, which bears the date 1627, and has apparently scarcely been touched since. The large mullioned window lights a room beautifully panelled in the Jacobean style, said to have been used by Cromwell on his not very friendly visits to Banbury during the siege, when the ancient castle was entirely destroyed. Other houses with steeply-pitched gables, elaborately carved barge rafters, and old - fashioned windows, date back almost to the Tudor period, and are carefully preserved by the inhabitants. The nursery rhyme suggests a visit to Banbury Cross, but the stranger only finds a modern Gothic, erection of good design, but surrounded by some hideously incongruous street lamps. Leland, in his description, speaks of the “goodly Crosse Home with many degrees about it, situated in “the fayrest street of the toune,” which of course shared the fate of all similar erections in places visited by the Puritan soldiers. For many generations Banbury had a reputation for being particularly zealous in matters relating to religion, and a proverbial expression in the seventeenth century was “Banbury zeale, cheese, and cakes.” An old engraving often seen in local curiosity - shops illustrates the following lines

To Banbury came I, oh profane one,

There I found a puritane one,

Hanging of his cat on Monday

For killing of a mouse on Sunday.

Previous to the year 1790, Banbury church was, according to history, which is confirmed by contemporary pictures, a magnificent Gothic, structure, almost worthy to be called a cathedral; unfortunately in that year the plea was put forward that the church was dilapidated and beyond repair, and the building was pulled, or rather blown down, by gunpowder, so firm were the ancient walls. The new church opened in 1797 is in the Italian style, and the exterior is not only unpleasing but positively ugly. The interior thirty years ago was dull and dismal to the last degree, but a change has taken place; successive vicars have addressed themselves to the task of beautifying the building, with the result that now Banbury Church is, inside, as attractive and interest ing, as the outside is the reverse.

There was, until the railway was constructed, a bridge over the river Cherwell here, with pointed arches built on parallel ribs, similar in many respects to the land arches of Old London Bridge; but one arch now remains over the side or mill stream, and this is almost hidden by the hideous viaduct and embankment which take the road over the railway.

Magdalen Tower and Bridge, Oxford.

For the next few miles the stream touches the parishes of Bodicote and Adderbury on the right or Oxfordshire bank, and Warkworth and Middleton Cheney on the left or Northamptonshire side, but there is no adjacent village until King’s Sutton is reached. This small collection of houses has a dilapidated, uncared - for appearance when seen either from the railway or the river, but is redeemed by the beauty of its church spire, a conspicuous object in the landscape for many miles along the valley; it has been compared with its neighbours, which are equally remarkable, in the following lines; —

Bloxham for length,

Adderbury for strength,

And King ' s Sutton for beauty.

There is a lightness and grace in this fine specimen of the early perpendicular style which perhaps warrants the verdict of the stanza. This parish was in the Saxon days one of vast importance, stretching a distance of twenty to thirty miles, and may possibly have been a royal demesne, which would account for the name. W. L. Bowles, the poet, antiquary, and divine, was born at King's Sutton in 1762, his father being the vicar. Only students now read the works of Bowles, whose first effort was a collection of sonnets published in 1789, which is said to have delighted and inspired the genius of Coleridge, then seventeen years old. Later in life he prepared and edited an edition of Pope's works, which produced a lively controversy in which Byron, Campbell, and others took part, the point at issue being whether Pope most inclined to the natural or artificial side of life. In this parish is the hamlet of Astrop, famous for a mineral spring called St. Rumbald's Well, said to have valuable medicinal quali ties, which many years ago attracted visitors from a distance, but is now seldom used even by those living in the neighbourhood.

Below King's Sutton the Cherwell receives on the Oxfordshire side the tributary waters of the Sorbrook and the Swere, either of which can in ordinary seasons be navigated by a canoe for two or three miles, and both afford some fairly good fishing, for which of course permission has to be obtained from owners of the adjacent land.

Aynhoe is the last Northamptonshire parish washed by the Cherwell, but the village is some distance from the stream. Here flourished in the earlier days of the present century a schoolmaster, the Rev. William Leonard, who possessed a considerable reputation as an instructor in the classics. Some of his pupils are still alive and tell amusing tales of his method, which consisted of the fortiter in re rather than the suaviter in modo; but for all that his old pupils subscribed for a memorial brass erected in Newbottle Church when he died about twenty years since. Opposite to Aynhoe is the parish of Deddington, but the so-called town is two or three miles away, and scarcely within the compass of this article. The hamlet of Clifton which abuts on the Cherwell has a deserted, melancholy appearance, relieved only by “The never - failing stream, the busy mill.” “The decent church” is absent, but a neat little chapel-of-ease was erected in 1853 for the use of the few inhabitants. Some thirteen years ago the Hon. Geoffrey Hill brought his pack of otter hounds and hunted the Cherwell valley for about a fortnight, causing a great sensation in the sleepy district. A few “kills” were made and the sport afforded was much enjoyed. The stream having many branches in the locality it was often found necessary for those who wished to see the hounds at work to wade and even to swim, and few returned from the chase with dry feet. As otters are com paratively scarce and the stream is too wide and deep for the ordinary practice of the sport, the experiment has not been repeated.

Now Oxfordshire is on either hand — Souldern on the left bank and the southern portion of Deddington as before mentioned on the right.

This is so thoroughly typical a portion of the Cherwell that a slight digression may be pardoned while some of the chief characteristics are pointed out.

The river twists and winds, then divides to form a mill head, there being a weir or lasher at the point of division; each side is lined with willows, cheerful in their full summer dress, but sad and depressing to look upon in winter, and when pollarded. The poles grown on these willows are used for making the light open hurdles common to the district. The numerous mills are often the cause of severe loss to agriculturists, for those who formed the mill heads in their desire to attain sufficient fall, raised the height of the water above the meadows by embankments, trusting to the lashers to take away superabundance of water; these however cannot prevent filtration, and the heads being nearly always kept full, materially hasten the floods in time of rain. A summer flood is most disastrous to the crops of hay, and although an occasional over flow at other times is beneficial, too much renders the grasses coarse, and is fatal to some of the best varieties. Efforts have recently been made to mitigate the floods by cleansing and deepening the channel, with some measure of success, but unfortunately the soil and mud taken from the stream have been allowed to remain in heaps on the banks, greatly to the detriment of the picturesque character of the valley. Although it is not difficult to conjecture, or even ascertain, when the various Cherwell bridges were built, it is far otherwise with the construction of the mills, for the Domesday survey proves them to have been in existence in the days of the Confessor, and whether we owe them to the Romans or to our Anglo-Saxon forefathers must remain an open question. The Cherwell turns in all fifteen water-mills, all of which have what are known as “breast - wheels,” one effect of which is to prevent scour and cause mud to accumulate.

The village of Somerton is, unlike its neighbour Souldern, close to the river and canal; being, however, separated by the railway, seen from which the old church, parsonage, and houses around form a delightful picture. The Earl of Jersey is lord of the manor and chief landowner, which fact possibly accounts for Somerton having a less forsaken and better cared-for appearance than many other villages abutting on the Cherwell. It is particularly noteworthy as having been for generations the seat of the Fermor family, who always retained the more ancient faith, and to whose memory there is a mortuary chapel forming part of the church, and known as the Fermor aisle, wherein the antiquary will find records of the family in the shape of an altar, font, brasses, and other memorials. The aisle is divided from the church by an oak - screen of beautiful Perpendicular character. The heroine of Pope's Rape of the Lock was Arabella Fermor of this same Somerton family, of whose mansion the only remnant is a ruined piece of wall with Gothic window directly overlooking the Cherwell valley and the village of North Aston on its other side. Bishop Juxon, who attended Charles I. on the scaffold, was rector of Somerton, and his arms, carved in oak, are still preserved in the church. The remains of the old village cross in the churchyard and a curious carved altar - piece representing the Last Supper, are features of the church and precincts, which all bear the stamp of remote antiquity.

North Aston is on an eminence which rises rather abruptly from the river. The church and mansion are close together, there being but an infinitesimal space between the east wall of the latter and the tower of the former, which in consequence appears dwarfed and insignificant.

It should be mentioned here that there are three Astons — North, Middle, and Steeple, all bounded on one side by the Cherwell; but Domesday book speaks of the whole area as “Estone.” The church at Steeple Aston is conjectured to have been erected before that at North Aston, and thus to have gained the special prefix to the name of the village. North Aston church was restored by the late Sir Gilbert Scott, and is well worthy of a visit; it contains an ancient altar-tomb supporting the effigies of Sir John and Lady Anne, who died in 1416.

First Bridge over the Cherwell, Charwelton/

John Hough, the President of Magdalen, who was removed by the infatuated James II., and whose biography is part of the history of the nation, held the vicarage of this parish, which he ceded on his election to the Presidency. Bernard Gates, the composer, said by Burney in his History of Music to have introduced oratorio into England, is buried at North Aston, and there is a tablet to his memory in the church.

Steeple Aston is a picturesque village about a mile from the river, on whose opposite bank is Upper Heyford, or according to its more ancient title, Heyford Warren. Here on a hill overhanging the canal and stream, which are only separated by the towing-path of the former, are clustered together the church and mansion house, with a remarkable old tithe-barn built by William of Wykeham, whose arms are sculptured on one of the buttresses of the church. This celebrated bishop and architect, who at the end of the fourteenth century, purchased the manor and advowson of the rectory, settled them upon his newly - constituted college of St. Mary de Winton in Oxford, still known as New College, and the property has remained in the hands of the Warden and Fellows of that society during the five centuries which have since elapsed.

A flood in March, a flood in May, Plenty of grass, but no good hay,

is an old adage here, but only one May flood has been known in the last twenty years. The old Mill at Upper Heyford has a tragic interest, as its occupant was shot in 1863 by his daughter ' s lover, apparently without any adequate motive. The crime was committed on the high road as the victim was returning from Bicester market, and the perpetrator was speedily brought to justice, and suffered the extreme penalty of the law.

Lower Heyford, or Heyford Purcell, is lower down the stream, and has a large corn mill and a good, well-restored church, so placed as to form a landmark; the tower has the rather unusual feature of a solid parapet, and the sun - dial over the south wall bears the quaint motto — Nil nisi cælesti radio. This parish has a third title, as the lords of the manor, viz., the President and scholars of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, invariably speaks of it as Heyford-at-Bridge, and this brings us to the old bridge and causeway running at right angles across the valley, which afford the only means of communication between one side of the Cherwell and the other for several miles. That the bridge was originally very much narrower than at present is proved by the arches on the down-stream side being pointed and ribbed; they are also far more substantial than the modern widening on the northern side. The date of the original erection is arrived at on this wise: in Kennett’s Parochial Antiquities a list of incumbents is given, in which those before 1275 are styled Rectors of Heyford only, but after that date they are invariably styled Rectors of Heyford ad Pontem. The stream widens out south of the bridge over a shallow, and here probably was the ancient ford which it is conjec tured gave the name to the place, i. e. the ford through which the hay grown in the valley was carted. This suggested derivation is given with some diffidence, but it has the advantages both of simplicity and probability. The trees near Heyford Bridge are of great beauty, and many of them of remarkable size. They are fully described by the following paragraph from the pen of the late Rev. J. C. Clutterbuck.

Not only is the soil well fitted for agricultural purposes, but it is no doubt due to the geological conditions of the colitic - rock and sand resting on the underlying lias clay that the wonderful and majestic growth of forest and other trees is due. This is, perhaps the most striking feature of the locality. Many of the trees have doubtless been carefully planted from time to time. The stately cedar of Lebanon, larch, and other trees of foreign origin, seem to vie with the indigenous oak, beech, elm, and other trees, with which the bank rising from the river and the park above are more or less clothed, and are fitted to raise the admiration of those who delight in the forestry of England.

The park alluded to is that of Rousham, which is bounded by the Cherwell, and has long been the seat of the Cottrell-Dormer family. The grounds adjacent to the river are, indeed, very beautiful, and may be seen at their best in the season of autumnal tints, when the chestnuts forcibly recall Mr. Vicat Cole's fine picture Autumn Leaves. There are many statues after the fashion of the last century, and a cloistered walk which commands a view of the valley. Down by the river, over a clear pool formed by a landspring, is a tablet with the following lines

“Tyrant of the Cherwell’s flood

Come not near this sacred gloom,

Nor with thine insulting brood

Dare pollute my Ringwood’s tomb.

“What though death has laid him low,

Lives the terror of thy race!

Couples taught by him to know,

Taught to force thy lurking place.

“Hark how Stubborn’s “airy tongue”

Warns the time to point the spear!

Rufin loud thy knell has rung,

Ruler echoes death is near.

“All the skies in concert rend,

Butler cheers with highest glee,

Still thy master and thy friend,

Ringwood, ever thinks of thee.”

These were written by Sir Clement Cottrell - Dormer early in the present century to the memory of a favourite otter-hound.

The mansion was originally built about 1635, added to in 1753, and very much enlarged since . It contains a whole succession of family portraits from the days of Queen Elizabeth downwards, with many other fine pictures by old masters The front door is loop-holed for defence, and the entrance hall is decorated with muskets and other arms of the seventeenth century . In earlier days there was a terraced garden descending from the house to the river, but that has long since given way to a verdant slope, on the top of which is one of the finest old bowling - greens in the country. Rousham church is also near the river; it is curious after seeing the mansion to note in the church the tombs of the different Dormers whose portraits have just been inspected. The village should not be left without a peep at the large walled kitchen - garden in the highest possible state of cultivation, and a careful examination of the ancient dovecote with its internal revolving ladder.

Enslow Mill, from above/

Tackley is the parish immediately below on the right bank, opposite to which is Kirtlington, but in neither case are there any houses adjacent to the stream . There is a bridge at a farm called Northbrook, but it only gives access to the meadows, and has no causeway like Heyford. The old Roman military road - Saxonized as Akeman-street - is easily traced in both these parishes, but there is no sign of ford or bridge where it crossed the river .

As there are here quite five miles of the Cherwell without a mill, the river increases in volume considerably above Kirtlington, and there is ample room for a pleasure boat; the sedge in places grows very high on both banks, and in the height of summer a wayfarer by water feels quite shut in and solitary, the only relief being the occasional sortie of a moorhen. Both the white and yellow water lilies grow luxuriantly on the Cherwell, and there are magnificent beds of the former in many places.

Kirtlington Mill with its broad head of water makes a fine picture, and apparently does a good trade . Adjoining is a public - house, the “Three Pigeons,” a favourite halting place for canal boats whose occupants are not likely to have read Goldsmith, or they might say with Tony Lumpkin —

Let some cry up woodcock or hare,

Your bustards, your ducks or your widgeons;

But of all the gay birds in the air,

Here’s a health to the Three Jolly Pigeons.

Below the river winds so much that it is three times crossed by the railway in the course of the next two miles, which bring us to Enslow Mill, in the parish of

Bletchingdon. Here there is a small station and a cluster of tenements, including a roadside inn. There are several stone quarries in the neighbourhood, and the hamlet is frequently called “Gibraltar,” from its rocky character Half a mile lower down is the substantially built Enslow Bridge, which with its causeway across the valley carries the main road from London to Chipping Norton. The rock, full of geological interest, rises high to the right for the next half mile, at the end of which a timber foot - bridge marks the confluence of the Cherwell with the Oxford canal, and united they form a broad but winding sheet of water for a mile or more; the canal, which has come in on the left bank, sheers off to the right, the Cherwell proceeding to turn Hampton Gay paper mill: that is to say, this was the former function of the stream, but the Hampton Gay of to day sadly belies its name. The mill is disused, and the adjacent Elizabethan manor-house, having suffered from a fire, in 1887, has nothing left but the walls and windows. The little church, which has its churchyard divided from the open field by an old-fashioned sunk fence, adds to the melancholy of the scene, for its ordinary poverty of appearance is enhanced by the air of neglect which pervades the edifice and its surroundings. A footpath across the meadows leads from this sad scene by a foot - bridge over the river directly to the church and village of Shipton-on-Cherwell. The railway bridge over the canal here was the scene of the terrible catastrophe on December 24, 1874, which will be fresh in the memory of many readers. There is a monument to one of the victims in Hampton Gay churchyard, which however bears no mention of the accident. Shipton church is pleasantly situated on a knoll above the canal and river, but lacks interest, as all, except the chancel, was rebuilt about 1831; the graveyard is remarkably well cared for and contains a restored village cross. The Great Western railway and the Oxford canal, which first came into contact with the Cherwell at Cropredy, now leave the valley and take an almost parallel and direct southern route to Oxford.

The river bears away a little to the south-east, and the large village of Kidlington on the right, is faced by Hampton Poyle. The first - named has a church with a tall spire, and the fabric is throughout in good preservation, being chiefly of the Decorated period. From the days of the Reformation until 1887 the living of this parish was held by the successive rectors of Exeter College, Oxford, the present incumbent being the first resident vicar for more than three hundred years.

Hampton Poyle, although small, is a far more cheerful place than its namesake; the church is a good example of the period of transition from Early English to Decor ated architecture, and contains a brass to one John Poyle, dated 1424, which gives a clue to the affix to the name of the village. At the hamlet of Gosford is a bridge of no particular character, but important because there is not another until Magdalen Bridge, Oxford, is reached; and that is approximately eight miles away as the river flows. At Islip, the Cherwell receives the tributary waters of the Ray, and the village is really situated on the banks of the latter. This place is celebrated as being the un doubted birthplace of Edward the Confessor, whose father Ethelred had a palace here. The chapel in which it is supposed Edward was christened was maintained until dese crated by the troops of Cromwell; it was afterwards converted into a barn and disappeared entirely before the end of the last century. A font, still in existence, and preserved in the church of Middleton Stoney near Bicester is said to have been brought from the Islip Chapel; it bears a mutilated inscription recording the tradition, but its tracery resembles work of the fourteenth century, rather than the rude masonry of the Confessor's days. Islip was frequently visited by the opposing forces during the Civil War, and in 1644-5 some serious skirmishes took place, one of sufficient importance to be recorded as the “Battle of Islip Bridge.” The living is in the gift of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster, and was held by Dean Buckland, father of the celebrated naturalist. The church is worthy of a visit, and, with the large tree which stands in the village street opposite the entrance to the graveyard, forms a good picture. The bridge over the Ray has recently been repaired and its former picturesque character is quite destroyed. The river from here to Oxford is the constant resort of boating - men, for although much impeded by weeds in places, the whole distance is fairly navigable for ordinary pleasure craft. Water Eaton on the right bank has a good manor - house with courtyard in front, and domestic chapel attached; there is a priest’s hiding - room over the front door; the buildings bear evidence of having been erected during the reign of James I. The artist and amateur photographer will find this portion of the river well worthy of study; there are many pretty “bits” and the vegetation on the Bletchingdon. Here there is a small station and a cluster of tenements, including a roadside inn. There are several stone quarries in the neighbourhood, and the hamlet is frequently called “Gibraltar, " from its rocky character Half a mile lower down is the substantially built Enslow Bridge, which with its causeway across the valley carries the main road from London to Chipping Norton. The rock, full of geological interest, rises high to the right for the next half mile, at the end of which a timber foot - bridge marks the confluence of the Cherwell with the Oxford canal, and united they form a broad but winding sheet of water for a mile or more; the canal, which has come in on the left bank, sheers off to the right, the Cherwell proceeding to turn Hampton Gay paper mill : that is to say, this was the former function of the stream, but the Hampton Gay of to - day sadly belies its name. The mill is disused, and the adjacent Elizabethan manor - house, having suffered from a fire, in 1887, has nothing left but the walls and windows. The little church, which has its churchyard divided from the open field by an old - fashioned sunk fence, adds to the melancholy of the scene, for its ordinary poverty of appearance is enhanced by the air of neglect which pervades the edifice and its surroundings. A footpath across the meadows leads from this sad scene by a foot - bridge over the river directly to the church and village of Shipton - on - Cherwell. The railway bridge over the canal here was the scene of the terrible catastrophe on December 24, 1874, which will be fresh in the memory of many readers. There is a monument to one of the victims in Hampton Gay churchyard, which however bears no mention of the accident. Shipton church is pleasantly situated on a knoll above the canal and river, but lacks interest, as all, except the chancel, was rebuilt about 1831; the graveyard is remarkably well cared for and contains a restored village cross. The Great Western railway and the Oxford canal, which first came into contact with the Cherwell at Cropredy, now leave the valley and take an almost parallel and direct southern route to Oxford. The river bears away a little to the south - east, and the large village of Kidlington on the right, is faced by Hampton Poyle. The first - named has a church with a tall spire, and the fabric is throughout in good preservation, being chiefly of the Decorated period. From the days of the Reformation until 1887 the living of this parish was held by the successive rectors of Exeter College, Oxford, the present incumbent being the first resident vicar for more than three hundred years. Hampton Poyle, although small, is a far more cheerful place than its namesake; the church is a good example of the period of transition from Early English to Decor ated architecture, and contains a brass to one John Poyle, dated 1424, which gives a clue to the affix to the name of the village. At the hamlet of Gosford is a bridge of no particular character, but important because there is not another until Magdalen Bridge, Oxford, is reached; and that is approximately eight miles away as the river flows. At Islip, the Cherwell receives the tributary waters of the Ray, and the village is really situated on the banks of the latter. This place is celebrated as being the un doubted birthplace of Edward the Confessor, whose father Ethelred had a palace here. The chapel in which it is supposed Edward was christened was maintained until dese crated by the troops of Cromwell; it was afterwards converted into a barn and disappeared entirely before the end of the last century. A font, still in existence, and preserved in the church of Middleton Stoney near Bicester is said to have been brought from the Islip Chapel; it bears a mutilated inscription recording the tradition, but its tracery resembles work of the fourteenth century, rather than the rude masonry of the Confessor's days. Islip was frequently visited by the opposing forces during the Civil War, and in 1644-5 some serious skirmishes took place, one of sufficient importance to be recorded as the “Battle of Islip Bridge.” The living is in the gift of the Dean and Chapter of Westminster, and was held by Dean Buckland, father of the celebrated naturalist. The church is worthy of a visit, and, with the large tree which stands in the village street opposite the entrance to the graveyard, forms a good picture. The bridge over the Ray has recently been repaired and its former picturesque character is quite destroyed. The river from here to Oxford is the constant resort of boating - men, for although much impeded by weeds in places, the whole distance is fairly navigable for ordinary pleasure craft. Water Eaton on the right bank has a good manor - house with courtyard in front, and domestic chapel attached; there is a priest ' s hiding - room over the front door; the buildings bear evidence of having been erected during the reign of James I. The artist and amateur photographer will find this portion of the river well worthy of study; there are many pretty “bits” and the banks is always luxuriant. Occasionally the Cherwell flows at the edge of its valley, and the rising ground adds to the effect of the landscape. Marston ferry enables pedestrians who have taken the pretty footpath from Summertown to cross the river and return to Oxford by way of St. Clement's and Magdalen bridge; this is a very favourite walk with both University men and citizens of Oxford.

The last two or three miles of the Cherwell are the most glorious, as they are the best known of its course. Skirting the suburbs of Park town and Norham Manor, the river forms the eastern boundary of the University park always spoken of in Oxford as The Parks. This fine area was, until about twenty - five years since, agricul tural land, but has been converted into a splendid open space and beautifully planted. In the centre is the University cricket ground, with its handsome pavilion, and at the south-west corner the new Museum, Observatory, and Laboratories. Leaving the parks, “Parson's Pleasure” is reached. This is a famous bathing-place, where a re freshing “header” can be enjoyed in all its luxuriance, and a swim taken down stream to a point which formerly ( perhaps the name has been forgotten ) was known as the “Devil’s Eye " so - called from its immense depth. Here part of the stream falls over a lasher; there are therefore two rivers, and a walk between the willow - bordered streams had been christened “Mesopotamia.” It should be noted that another stream leaving the main channel above the “Pleasure” ( which is sometimes called Logger head ), goes away to the right and turns Holywell Mills. The various branches meander around the magnificently - timbered demesne familiar to every visitor to Oxford as Magdalen Water Walks.

Waynfleet, Bishop of Winchester, was the founder of the magnificent college of St. Mary Magdalen, any description of which would take many pages and, moreover, be superfluous, so well known are the grand and gray old buildings.

Magdalen bridge and tower have been depicted in every form of pictorial art, over and over again, and form an admirable composition from whatever point a view is taken. The former was widened in recent years. When the idea was first mooted a storm of controversy arose, fears being entertained that the beautiful character of the architecture would be impaired Happily these fears were found to be utterly ground less; the Oxford Local Board, the body responsible for the work, carried it out in strict conformity with the old design, thereby effecting a great public improvement without damaging the artistic character of the surroundings. The approach across the bridge from the Henley road gives a better view than formerly of the college tower, and when the new stone becomes a little more mature in colour, the most con servative in such matters should become reconciled to the change. There are, how ever, those who will always think it sacrilege that the tramcars should run over this classic structure.

The remaining reaches of the Cherwell should be seen in the height of the Oxford May term, for then they are alive with craft of many descriptions. To “Cherwellize” is Oxford for the practice of punting up the winding stream until a sequestered and shaded spot is reached, when the punt is moored, and its occupant proceeds some times to read, and almost invariably to smoke. Canoes flash up and down in every variety, double and single, Canadian and English, and often “pair - oars” and the teetotum - like “cockle” add to the variety of the scene, which is still more enlivened by the brilliant colours of every sort and shade worn by those who take this form of pleasure. Every turn of the Cherwell round Christ Church Meadow reveals a new picture, until the “last stage of all” is reached — its confluence with the Thames, which is now marked by a rustic wooden foot-bridge. A straight canal - like cutting has been made to discharge part of the Cherwell water at a point lower down the Thames, which future historians may perhaps speak of as the junction of the two streams. As yet however the old land - mark preserves its old name, and many a rowing-man retains vivid recollections of frantic efforts to respond to stroke's spurt when his crew made their famous “bump at the Cherwell.”

The pilgrim of our inland stream having now arrived on the waters of the Thames can paddle up to Salter’s Barge and leave his craft or continue his voyage; in either case no further pilotage is needed. The botanist and naturalist will find the Cherwell valley a fine field for study, and those interested in dialects will not be unrewarded. Pure “North Oxfordshire” is a variety of the English language which is almost indescribable.

Bibliography

Wing, William. “The River Cherwell.” The English Illustrated Magazine. 8 (1880-1881): 484- Hathi Trust/span> online version of a copy in the University Library. Web. 21 January 2021.

Last modified 21 January 2021