In transcribing the following passage from the online version I have expanded abbreviations and added paragraphing, links, and illustrations. Unless otherwise noted illustrations come from Dent’s The Making of Birmingham — George P. Landow

The Free Grammar School Act of 1831 and Birmingham’s First Primary Schools

The passing of the act of 1831, which made it compulsory on the governors of the Free Grammar School to establish elementary schools. The first of these was in course of erection in 1837, “in the new street leading out of Aston Street,” to wit, Gem Street, “in the midst of a dense population,” and a second “was about to be commenced in Cottage Lane, near to the Sand Pits,” which afterwards came to be known as the Edward Street School. On April 10th, 1839, the third of these schools was opened in Meriden Street, Digbeth, and the fourth, near Hath Row, at a later date. At the close of the period under notice, the schools contained the following number of scholars in each department:

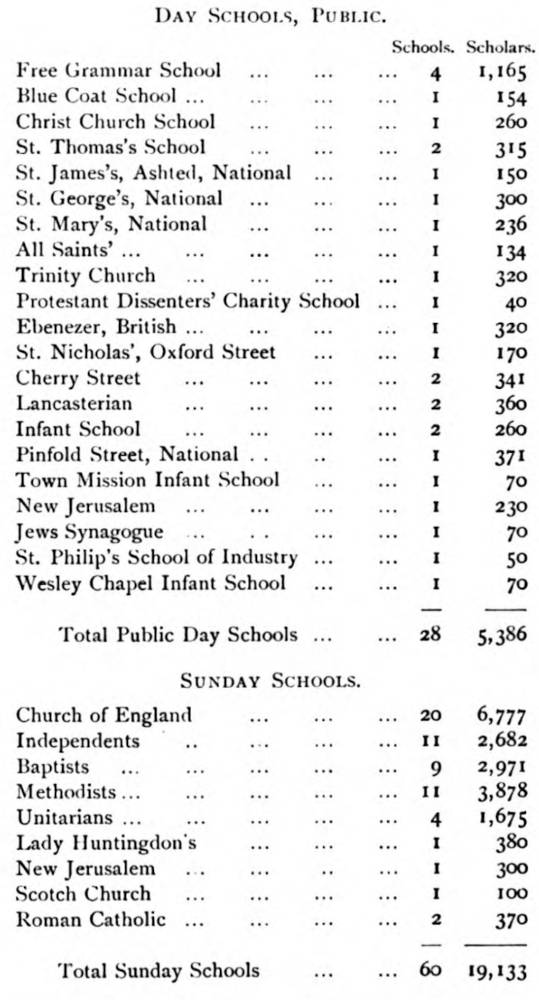

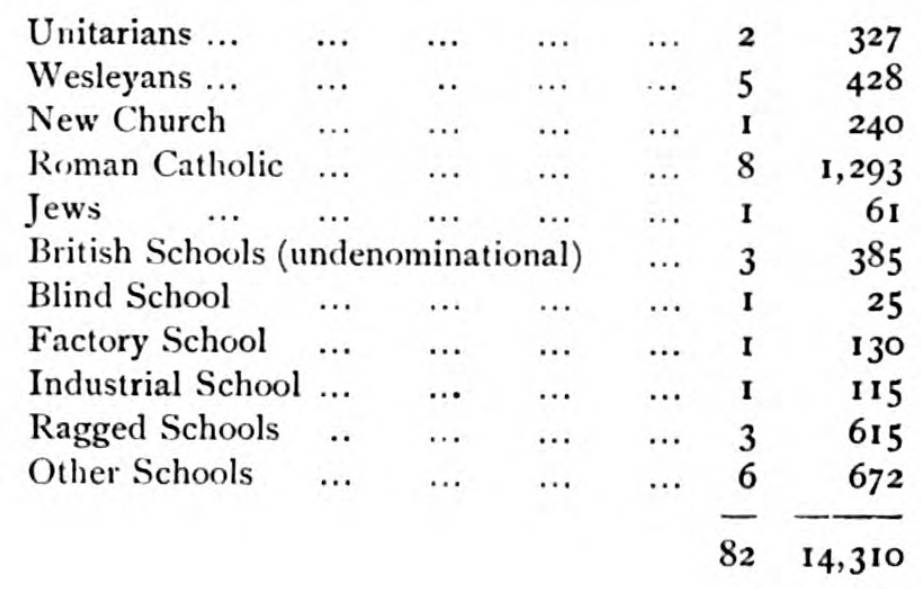

In 1842 a statement was published, as the result of personal enquiry, by Mr. Showed, as to the general school accommodation provided in Birmingham, follows:

A National School for the children of the Jews in Birmingham was established in 1843, the first stone being laid on the 9th of August in that year by Sir Moses Montefiore.

An Association for extending Infant Schools was established in Birmingham in 1846, and in a short time had raised £3,000 in donations and subscriptions. By the middle of 1848 they were able report that they had approved of localities for schools in the parishes of St. Martin’s, St. George’s, a St. Thomas’s, and in the districts of the churches St. Bartholomew, St. Matthew, St. Mark, St. Lul St. Andrew, and St. Peter. The first school open was one in Freeman Street, on November 10th, i8 and others followed in various parts of the town so afterwards.

Birmingham’s First Ragged School

A Ragged School was also founded in the town through the exertions of the Hon. and Rev. Granthi Yorke, rector of St. Philip’s, in the poor and densely populated neighbourhood lying between Dale and Steelhouse Lane. The school was opened Lichfield Street in 1846, and in little more than a year afterwards it was reported that 222 children had entered the School, which was under the care an experienced master. They were “watched over carefully; their faults patiently and kindly correct so as to win them by persuasion and gentleness fre the idleness and errors into which they may have unfortunately fallen; and every other day they receiv a substantial meal.” By 1850 three such schools were in existence in the poorer parts of the town.

The Proprietary School— Birmingham’s First Free Industrial School

A Free Industrial School was also founded during the closing years of this period in Gem Street. A handsome school building was erected in the Hagley Road between 1838 and 1841, which it was proposed to conduct on a novel system. It was to be the property of a number of shareholders or proprietors, each of whom should be entitled to send their children to be educated within its walls, and it was to be carried on on unsectarian lines, and without the infliction of corporal punishment. The Proprietary School, as it was called, became in a large measure successful, and was conducted on the principles thus laid down until about 1880, when it was taken over by the Governors of the Grammar School, and has since formed one of the Middle Schools of that foundation.

Thus was the school accommodation of all classes extended in the town, so that whereas in 1842, as we have seen, only twenty-eight Day Schools were in existence in the town, by the end of the half century the number had increased to eighty-two. During the last eight years of this period education had in fact made greater advances in our midst than in all the forty-two years preceding, as may be seen from the following table which Mr. Jaflfray gathered from the census returns of 1851.

Queen’s College

One of the most important events in the educational history of this period was the foundation of Queen’s College. Early in 1824 Mr. W. Sands Cox conceived the idea of founding a School of Medicine for Birmingham and the midland counties, and with a view to finding models for the projected institution, made a tour of inspection through the principal medical schools of the continent. On his return the following advertisement appeared in Aris’s Gazette, November 22nd, 1825 :

A Course of Anatomical Lectures, with Physiological and Surgical Observations, will be commenced on Wednesday, the 1st of December, 1825, at 12 o’clock. The Course will be continued during the ensuing winter, on Mondays, Thursdays, and Fridays, at 24, Temple Row.

The plan has met with the approbation of Dr. Johnstone, Dr. Pearson, the physicians and surgeons of the General Hospital, Dispensary, and Town Infirmary, and other distinguished practitioners.

Queen’s College, Paradise Street

From this humble beginning arose what might under happier conditions have become the University of Birmingham, and which has, in its day, occupied an important position among the educational institutes of Birmingham—Queen’s College. The School of Medicine and Surgery passed its infancy in Temple Row and Brittle Street [Brittle Street was a short thoroughfare between Snow Hill; Street, but was obliterated by the formation of the Great Wester Station.], a building being erected fitted up as a museum and library in the latter street near Snow Hill, by Mr. Sands Cox, at a cost of £1,100 But its founder’s ambition went beyond tbe establishiment of a School of Medicine and Surgery. He was desirous of founding a college in which Arts, Law, Engineering, Architecture, and General Science should also be taught, and in 1843 the school was incorporated by royal charter, as Queen’s College, further powers being conferred by a second and third charter in 1847 and 1853.The first stone of the college buildings, in Paradise Street, was laid by Dr. James Johnstone, on the 18th of August, 1843. The land on which it was built had a double frontage to Paradise Street and to Swallow Street of seventy-two feet, the distance between the two streets being one hundred and twenty feet, and was considered by the architects “the most eligible, in the centre of the town, on a remarkably elevated spot, opposite the Town Hall, on a sand rock, with excellent water, and complete drainage.” The building was designed by Messrs. Drury and Bateman, in the Tudor-Gothic style, resembling in general appearance the Free Grammar School, and comprised a museum, library, a large lecture theatre, laboratories, anatomical rooms, a dining hall, and apartments for seventy students, occupying the four sides of a quadrangle. A chapel was built through the munificence of Dr. Warneford, and was consecrated on the 15th of November, 1844, by the Bishop of Worcester. It contains a beautiful stained glass window, designed by Brooke Smith, jun., and executed by Messrs. Pemberton, and an altar-piece of silver, designed by Flaxman and executed by Sir Edward Thomason, the subject being “the Shield of Faith.”

The institution found many generous friends and benefactors during the earlier years of its existence, chief among them being Dr. James Johnstone and Dr. Warneford. The latter, in addition to building the college chapel, and founding scholarships, endowed the Wardenship and Chaplaincy, founded chairs of Pastoral Theology, Classical Literature, and Mathematics, and thus equipped the college for the education of candidates for Holy Orders, as well as of students for the Medical Profession.

The Founding and Failure of an Anatomy Museum

In 1857, a new museum building was erected with the help of many generous donors. This consisted of three large rooms, the largest of which was illustrative of comparative anatomy, botany, and anatomical preparations. Thus equipped, the college seemed to have embarked on a wide sphere of usefulness and prosperity; but from some cause it fell on evil times. Differences arose between the governing powers, the professors, and the supporters of the college. Large sums were spent in legal squabbles; the two branches of the college, the theological and the medical, seemed ill at ease under one roof; the contents of the museum were carted away to Aston Hall, and the handsome museum buildings were advertised to be let for an auction-room or a Manchester warehouse, and were, indeed, subsequently let to a paper-hanger and decorator. At the present time the only portion of the college course carried on within the building is that of the Theological department, the Medical and Scientific departments having been transferred to a new'er institution, the splendid Science College founded by Sir Josiah Mason, of which we shall have to speak in a future chapter.

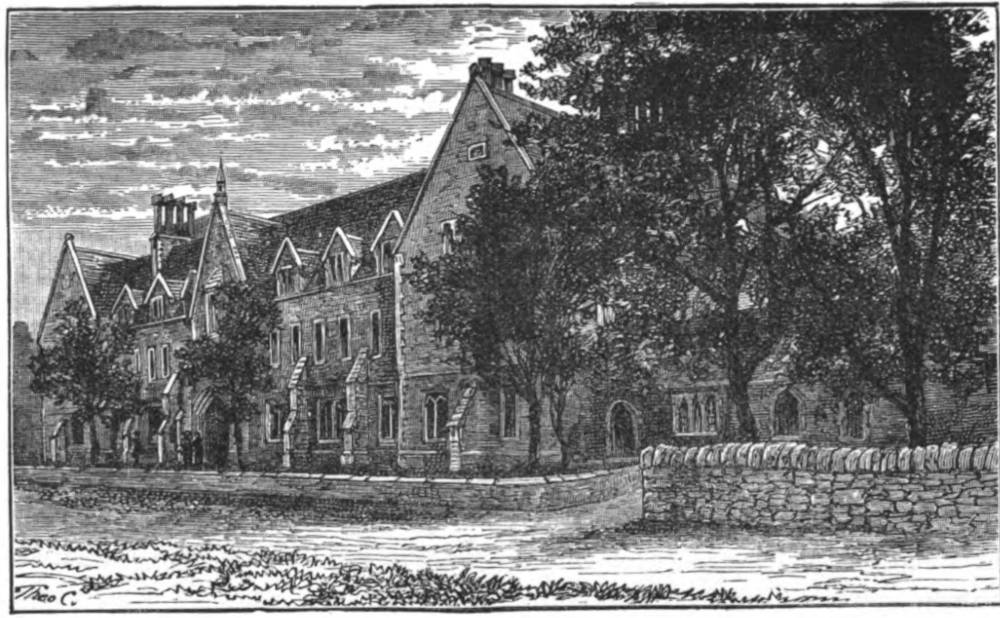

Saltley Training College

In 1847 an institution was founded in the neighbourhood of Birmingham for the training of Church of England schoolmasters for the dioceses of Worcester, Lichfield, and Hereford. Nearly £10,000 was raised for this purpose, and a site was given for the proposed college at Saltley by Mr. C. B. Adderley, the present Lord Norton. The first stone was laid by Sir John Pakington, on the 10th of October, 1850, and at Easter, 1852, the institution was opened. The building was designed by Mr. B. Ferrey, in the Gothic style of Edward I., and it is built of hard red sandstone with Bath stone dressings. It comprises a lecture hall, dining hall, class rooms, laboratories and other offices, with dormitories for the students, and a residence for the Principal. During the forty-three years in which this Institution has been in existence it has trained nearly two thousand masters, who have taken positions not merely in the day schools of the Church of England, but also in the board schools of the midland counties generally. A prize of the value of £20 a year was founded by Colonel Ratcliffe, and a second of the value of £5 5s. by the governors; and there are also four exhibitions of ^10 a year, each, tenable for two years, the gift of an anonymous friend. In 1857, a new museum building was erected, with the help of many generous donors. This consisted of three large rooms, the largest of which was forty feet square and forty feet in height, and surrounded by two tiers of galleries. It comprised the museum of natural history formed by Weaver, also collections occupied as banking premises by Messrs. Galton anc James. They purchased the library of the Mechanics Institute from Mr. Sturge, and in October in the sam< year the library and news rooms were opened and th< classes commenced. The Polytechnic Institution pursued a successful course for a considerable time but at the end of ten years it too passed out o existence. Well might the author of the ‘Hints’ sa) the history of the literary and scientific societies o Birmingham of that period was ‘altogether disheartening! ’

The Birmingham Society of Arts and School of Design

An important development of the work of the Birmingham Society of Arts was brought about during this period which resulted in the establishment of a School of Art which has borne much fruit in the creation of a local school of designers and painters and has had a long and honourable career as one o the most successful Art Schools in the provinces. . . . It was not until 1842 that the struggling local society found themselves in a position to obtain help from government to enable them to carry on their work. . . . The artists seceded from the society and formed the Birmingham Society of Artists, which for many years held its exhibitions in Temple Row.

The first year’s grant obtained from government amounted to £150, and with the help of donations from Sir Francis Lawley and other friends of the society, the School of Design was fairly launched in i843, with Mr. Dobson as teacher, and from this time the Society became known as “The Birmingham Society of Arts and School of Design. By May, 1844, there were 243 students enrolled on the books, and an assistant master was appointed. Year by year the number of students increased, and by the close of the half-century the school was in a flourishing condition. In 1851 Mr. George Wallis was appointed head master, and retained that position until 1857, when he was compelled to resign in consequence of ill-health. During this brief period, however, he had succeeded in impressing the school with his own personality, and by his labours largely helped forward the success of the institution.

Soon after the completion of the Birmingham and Midland Institute . . . , the School was removed to a portion of the Institute premises, and remained there until the erection of the present Municipal School of Art. The last report of the Society of Arts and School of Design was issued at the end of 1884, in which the committee expressed their gratification at being “able to claim for the School a vigorous and prosperous life.” The high level of excellence reached in previous years had been fully maintained, and when in the course of the following year (1885), in accordance with the scheme of the Corporation to found a Municipal of Art, the transfer of the School to the Town Council took effect, they were able to hand over for municipal management “a School of Art worthy of the town and justifying the recognition which it had received by the burgesses and their representatives in the Town Council.”

Related material

Bibliography

Dent, Robert K. The Making of Birmingham: Being a History of the Rise & Growth of the Midland Metropolis. Birmingham: J. L. Allday, 1894. Birmingham: Hall and English, 1886. 438-44. HathiTrust online version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 4 October 2022.

Last modified 5 October 2022