In transcribing the following passage from the online version I have expanded abbreviations and added paragraphing, links, and illustrations. — George P. Landow

The Church of England and the Church Building Society

The Commissioners who were entrusted with the expenditure of the parliamentary grant for the erection of new churches having provided church accommodation for the outlying districts on the north and south, next turned their attention to the more populous centre; and on the 27th of July, 1825, the memorial stone of a new church in Dale End was laid with due ceremonial. This was to be dedicated to St. Peter, and was designed by Messrs. Rickman and Hutchinson, in the classic style of the Georgian period. The architects were doubtless ambitious of erecting a worthy rival of Christ Church, and, like that edifice, the new church was provided with a massive portico supported on four Doric columns. They wisely adopted a form of turret more in harmony with the rest of the building than is the spire of Christ Church, however, and chose for their model the Tower of the Winds, in the Temple of Minerva at Athens. It took the form of an octagonal turret, encircled by a colonnade, and in its construction the masonry was executed in a similar manner to that of the original from which it was copied, large blocks of stone being used, some of them weighing upwards of seven tons, while the centrepiece of the architrave measured more than thirteen feet in length. These stones were obtained from the quarries at Guiting, in Gloucestershire. The expense of the site and building of this church together amounted to £19,676 2s. nd., and it was consecrated on the 10th of August, 1827. “The interior, as well as the exterior of the edifice,” we read, “was much admired; the style is Grecian, and reflects great credit upon the architects, Messrs. Rickman and Hutchinson.” It was calculated to seat 1,900 persons, the greater portion of the sittings being free. The expense of erection proved to be £822 less than the estimate.

Little more than three years after its consecration a fire broke out in this church and left scarcely a vestige of the interior work remaining. The fire occurred during the night of Monday, January 23rd, 1831, and seems to have originated in connection with a flue at the east end of the church, and had made very considerable progress before the alarm was given. In less than an hour after it was discovered the roof fell in, and destroyed the organ, pulpit, and altar-piece. At the western end of the building the fire reached the woodwork of the belfry, and after burning some time the cross and bell fell, and carried with them a considerable part of the gallery staircase. The work of restoration was not completed until 1837.

The growth of the town westward, between Holloway Head and the Five Ways, had called into existence a new town district at a considerable distance from any church, and a few weeks after the first stone of St. Peter’s had been laid, the Church Building Commissioners met to consider several designs which had been submitted for the erection of a church in that neighbourhood, to be called St. Thomas’s. The plans of Messrs. Rickman and Hutchinson, the architects of St. Peter’s, were selected for the new church, and the first stone was laid by the Bishop of Worcester on the 2nd of October, 1826. The building was completed in 1829, and consecrated on the 22nd of October in that year. Again the architects had chosen a classic style, the only adornment being a semicircular colonnade of massive Ionic pillars, supporting the porch, and surrounding the base of the tower at the western end. This latter is not unlike the towers of some of the London city churches designed by Sir Christopher Wren; it rises in two sections or stories, and is terminated by a gilded ball and cross. From the southern and western end of the town this tower is a conspicuous object, and can be seen at a considerable distance. The entire cost of building, amounting to £14,222, was defrayed out of the parliamentary grant. This church is said to be the largest in Birmingham, and provides accommodation for 2,600 worshippers, 1,500 of the seats being free. This was the last of the churches provided in Birmingham out of the parliamentary fund. It will be remembered that St. Thomas’s churchyard was the scene of one of the most dangerous outbreaks during the Chartist agitation, when the mob wrenched out the iron palisades surrounding the enclosure and converted them into pikes.

In November, 1829, a meeting was held, attended by the clergy of the several churches and episcopalian chapels in Birmingham, whereat it was decided by mutual arrangement to divide the large portion of St. Martin’s, which remained after the separation of the new parishes of St. George’s and St. Thomas’s, into small districts, each minister taking charge of that portion which immediately surrounded his own church or chapel, “with a view to remedy the deficiency of spiritual superintendence which the want of ecclesiastical division necessarily creates.”

The scattered population which had been drawn into the neighbourhood of Soho and Hockley through the enterprise of Boulton and Watt was the next to be provided with church accommodation, by the erection of All Saints’ Church, near Lodge Road, in 1833. “When the church was erected,” says a recent writer,* “the suburb of Nineveh was far in the country, the nearest cluster of dwellings of any importance was at Hockley, in the neighbourhood of the Old Cemetery. Farmhouses and cottages were scattered at intervals in the fields and lanes which surrounded the church on all sides. Looking from the Old Cemetery the church was the one prominent feature in the landscape, its dwarf spires rising above the surrounding trees. From Key Hill a rural lane led up to it, lined with hedgerows, amid which twined the honeysuckle and the wild rose. Cornfields and hayfields were on either side the road. A lane to the left led through the meadows to Birmingham Heath. There was another way to the church from the bottom of Warstone Lane, over stiles by pathways through the fields, wrhere murmuring brooklets crept along, where cowslips grew, and Madysmocks all silvery white’ might be gathered for the trouble of stooping.”

The church, which was erected in the Gothic style of the 13th century, was designed to accommodate about a thousand worshippers, and was, consecrated on the 28th of September, 1833, by Bishop Ryder, of Lichfield, who had taken great interest in its erection.

The good Bishop of Lichfield was deeply interested in the spiritual welfare of Birmingham, and after the completion of All Saints’ Church he turned his attention to the dense population growing up in the neighbourhood of Aston Street and around Gosta Green, and greatly interested himself in the proposal to erect a church in this neighbourhood. He induced several wealthy landowners to assist in this undertaking, but did not live to witness its accomplishment. On the 22nd of August, 1837, the first stone was laid of a new church which was to be built in Gem Street, midway between Aston Street and Coleshill Street, and in commemoration of the labours of the late Bishop of Lichfield for the spiritual welfare of the people of Birmingham, the Church Building Society took the unusual and unconventional course of dedicating it to his memory. An interesting incident in connection with the stone-laying ceremony is thus recorded in the Gazette of August 27th, 1837 :

On Wednesday last, during the assembling of the clergy and gentry who took part in the procession at the laying of the foundation stone of Bishop Ryder’s Church, in this town, a very beautiful medallion of the size of life of the late Bishop, the work of our townsman, Mr. Peter Hollins, was exhibited at the Blue Coat School. Many of the Bishop’s friends who were present, including the Rev. John Kempthome, Chaplain to his Lordship when he presided over the See of Gloucester, pronounced the likeness, considering the circumstance under which it was produced (being altogether a posthumous work), a most extraordinary resemblance. It is a profile in low relief, and is intended to form part of the monument to he placed in the parish church of Lutterworth, where the pious anti worthy successor of Wickliffe was for many years the affectionate and beloved minister.

Bishop Ryder’s Church was consecrated on the 18th of December, 1838. It is a red-brick building, Gothic in style, and is relieved by a lofty and handsome brick tower, with stone dressings.

On the 17th of August, 1836, the first stone of a new episcopal chapel for Edgbaston, to be called St. George’s, was laid by the Rev. Charles Pixell, Incumbent; and the building was completed and consecrated November 28th, 1838. The following notice appeared in the Gazette of December 3rd :

The elegant Chapel, recently erected at Edgbaston by Lord Calthorpe, with a view to the supplying of the additional accommodation so much required for the purposes of public worship by the inhabitants of that parish, was consecrated by the Right Rev. the Lord Bishop of Worcester on Wednesday morning last. The site of this truly beautiful edifice was the gift of the Noble Lord, and the structure itself was erected by his Lordship at the expense of nearly ^6,000, with the exception of £500 bequeathed by the late Mr. Wheeley. Lord Calthorpe, in addition, has very handsomely endowed the building, and provided the communion plate, service books, &c., &c. For the use of the poorer inhabitants two hundred free sittings are reserved ; and the remainder are to be rented, according to their various situations, at 20s., l6s.f and 12s. per annum.

The steady and constant growth of the town necessitated increased effort to provide for the spiritual needs of the new suburban districts which were growing up around the mother-town, covering the pleasant allotment gardens with brick and mortar, and gradually absorbing all the open space within the boundaries of the borough on all sides. To cope with this necessity, a new’ association wras formed, mainly through the exertions of the Rev. John Garbett, the Rural Dean, for the purpose of raising funds for the erection of ten new churches. The “Ten Churches Fund,” as it was called, did not, however, achieve all that was proposed, only five churches being built as the result of this association. The first of these was St. Matthew’s, which was built in Great Lister Street, a new thoroughfare cut across from Gosta Green to Saltley Road. The first stone of this church was laid on the 12th of October, 1839, and the building was completed on the 20th of October, 1840. It is a plain red brick Gothic structure, relieved with stone dressings, with lancet windows, and from the western end rises a square brick tower, surmounted by a stone spire. The first vicar was the Rev. G. S. Bull, who named the church “St. Mathew’s in the Wilderness.” The cost of erecting this church amounted to ,£3,200.

The Church Building Society next turned its attention to the north-western outskirts of the town, and having obtained a piece of land adjoining King Edward’s Road, as a gift from the Governors of King Edward’s School, the first stone of the new church, which was to be dedicated to St. Mark, was laid on the 31st of March, 1840. The church was designed by Mr. (afterwards Sir) G. Gilbert Scott, and is in the early English style. It consists of nave, chancel, and side aisles, with a tower and spire at the north-western angle. The stone used in its erection was of a perishable nature, and at the present time the tower and spire are under repairs. This church affords accommodation for a thousand worshippers, and was built at a cost of £3,100.

Following in the canonical order, the society, after having built St. Matthew’s and St. Mark’s, next undertook the erection of St. Luke’s, in Bristol Road, the first stone of which was laid on the 28th of July, 1841. This church was designed by Harvey Egginton, of Worcester, and is in the Norman style of architecture. Like St. Mark’s, it was built of a soft, perishable stone, and has ‘weathered’ badly. The building consists of nave, chancel, and side aisles, with a low tower at the south-west angle. It has 800 sittings, and cost upwards of £3,500 in erection. It was consecrated September 28th, 1842.

The fourth church built by the Church Building Society was St. Stephen’s, in Newtown Row. At the time of its erection there was a wide tract of waste land lying between that thoroughfare and Aston Road, and, like St. Matthew’s, the new church might be said to be ‘in the wilderness.’ The Order in Council for the formation of the parochial district of St. Stephen’s was calculated to give the stranger an impression that the new church was being planted in a district as yet unpeopled, for the boundaries of the area given therein were only defined by the banks of canals, brooks, and imaginary lines passing through the lands of various owners. The style adopted for this church was geometric Gothic, and the material was a soft friable stone which soon presented a worn and dilapidated appearance. The design included a tower at the north-eastern corner of the building, but this architectural feature never got beyond the height of the church, being terminated by an extinguisher-like cover to the solitary bell. The church was designed by Mr. R. C. Carpenter, and cost about £3,000. It was consecrated July 24th, 1844.

The efforts of the Church Building Society culminated in the erection of their fifth church, for which a site had been offered on the crest of the hilly ground known as Bordesley Green. This was as unsuitable a site as could be found for the proposed church. The immediate neighbourhood has never been in favour as a building estate, and for many years the only dwellings near the church were the huts of the brick makers working in the neighbouring brickfields, a few straggling cottages, and an occasional camp or caravan of gipsies or other wayfarers. The church itself is a plain structure in the Early Decorated style of English architecture, with a massive square tower, above which rises a stunted spire. It has a noble five-light east window, filled with stained glass; in the centre light is the figure of the apostle to whom the church is dedicated, St. Andrew, and in the side lights are figures of the evangelists. The foundation stone of this church was laid on the 23rd of July, 1844, and the building was consecrated September 30th, 1846. There are 800 sittings, 200 of which are free.

The Church-Rate Controversy

During this period the church-rate controversy was fought out in Birmingham with the earnest determination whiich had characterised the struggle for political freedom. Previous to 1830 the amount of this rate had varied from tenpence to eighteenpence in the pound, but in that year it was reduced to fourpence, and the same amount was levied in 1831. This was the last church-rate levied in the parish of Birmingham. At the meeting called for making a similar rate for 1832, on the 7th of August in that year, the nonconformists raised a fierce opposition to the proposal, and passed resolutions condemnatory of the system. The meeting was adjourned, but no further meeting was held that year, and the rate was not levied.

Controversy continued during that and the two succeeding years, and on the 5th of December, 1834, a great meeting was held in the Town Hall, to decide whether a new rate should be made. More than eight thousand people,” says Mr. JafTray, “were on that day crammed into the Town Hall, to decide whether they should or should not grant a church rate of 4d. in the pound. Lengthened addresses were delivered on both sides, sometimes amid great uproar and confusion. When the show of hands was taken, the rate was lost, but its supporters demanded a poll. For seven days—namely, from the 6th to the 13th of December—the poll was kept open ; but the feeling of the town was evidently with the anti-rate party from the first; and the result of the poll when it was closed by the Rev. Thomas Moseley, then Rector of St. Martin’s, was as follows :—

For the rate............ 1,723

Against it.............. 6,699

Majority.......... 4,976” [Hints for History pf Birmingham, ch. ../../../art/architecture/pugin/9ix]

This was but the first campaign in the contest, however. For several years the church-rate party made strenuous efforts to obtain the consent of a majority of the inhabitants to the granting of another rate, and twice were beaten by large majorities at the poll. The last poll on this question was taken in February, 1842, when 3,889 persons voted against, and only 89 for, a church rate; and thus ended the controversy on this question in the parish of Birmingham.

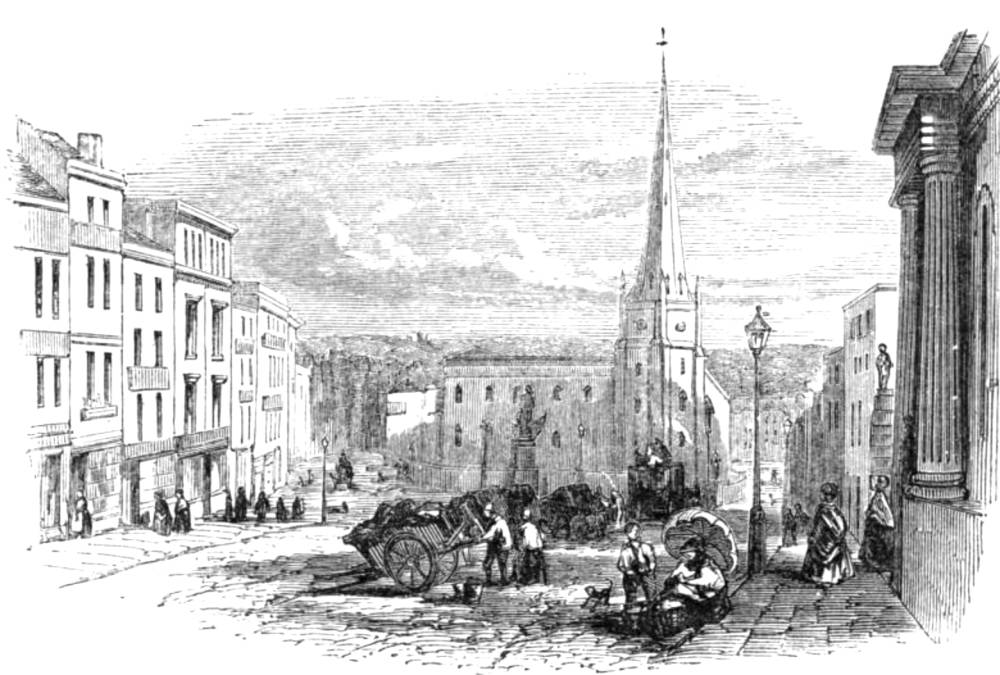

The Bull Ring and St. Martin’s Chuerch. Birmingham. From Nature on Wood by C. W. Radclyffe. Click on image to enlarge it.

The Unitarians

During this period a number of the members of the Old and New Meeting Houses left the parent churches and formed a new Unitarian Church for the northern end of the town. They met for some time in premises in Cambridge Street, but having received a donation of £1000 from Mr. Thomas Gibson as the nucleus of a building fund, they resolved upon the erection of a new chapel in Newhall Hill, the first stone of which was laid by that gentleman, in the presence of a large gathering of friends of the movement, on May 1st, 1839, a suitable address being delivered by the Rev. Hugh Hutton. The chapel was completed in 1840, and contains accommodation for 1,000 persons, a large schoolroom being constructed on the basement floor under the chapel. The cost of erection amounted to £3,000.

This denomination took an important step towards providing for the moral and spiritual welfare of the artisan population during this period, in the foundation of the Domestic Mission. Mr. Bourne was appointed as a town missionary in 1840, and in 1844 a small place of worship was opened in Hurst Street, which has ever since been a centre of Unitarian mission work.

The Baptists

The Baptists erected one new chapel during this period, and also converted a large building previously used as a circus to religious uses. The new chapel was erected in the rapidly growing district of Duddes-ton, in commemoration of the emancipation of the negro slaves in the West Indies. I .and was purchased in Heneage Street for this purpose, and a small building erected at a cost of £600. A larger chapel was erected on land adjoining the smaller building in 1840, by the united aid of the congregations worshipping at Cannon Street and Bond Street Chapels. The foundation stone was laid by Mr. Knibb, and the chapel was opened in 1841, having cost £4,000 in building.

The second enterprise of the Baptists during this period was the conversion of what had been known as Ryan’s Amphitheatre, in Bradford Street, into a place of worship. As a circus or amphitheatre it had proved a failure, and being offered for sale, “a wealthy and generous individual connected with the Cannon Street congregation, aided by others, and especially by the counsel, energy, and co-operation of Mr. Roe, of Heneage Street, purchased this building, and had it altered and arranged for the service of God. It was opened for worship in 1848.”[James’s Protestant Nonconformity, p. 178] Mr. James states that during the earlier years of this place of worship an individual officiated as door-keeper who had formerly performed as a clown in the same building in its circus days.

The huge chapel in Graham Street, which had been used by the Scotch Presbyterians up to 1826, remained empty for some time afterwards, but was purchased in 1827 by the Baptists, who re-named it “ Mount Zion,” and it was re-opened with the Rev. Mr. Thonger as minister. To him succeeded the Rev. Dr. Hoby, who held the pastorate until 1844. He was followed by the Rev. George Dawson, a young man of broad and liberal views, such as were hardly acceptable to the rigidly orthodox supporters of Mount Zion Chapel. “The congregation had long been dwindling under the charge of the Rev. Dr. Hoby, and the arrival of a young, earnest, and popular preacher, entirely unconventional in opinions, personal appearance, and style of preaching, soon attracted crowds of hearers. He preached his first sermon in Birmingham 4th August, 1844, ministered to the congregation till 29th December, 1845, apd attracted hearers from nearly all the other chapels, and especially large numbers who never attended religious worship.[Dictionary of National Biography [art. Dawson by S. Timmins].

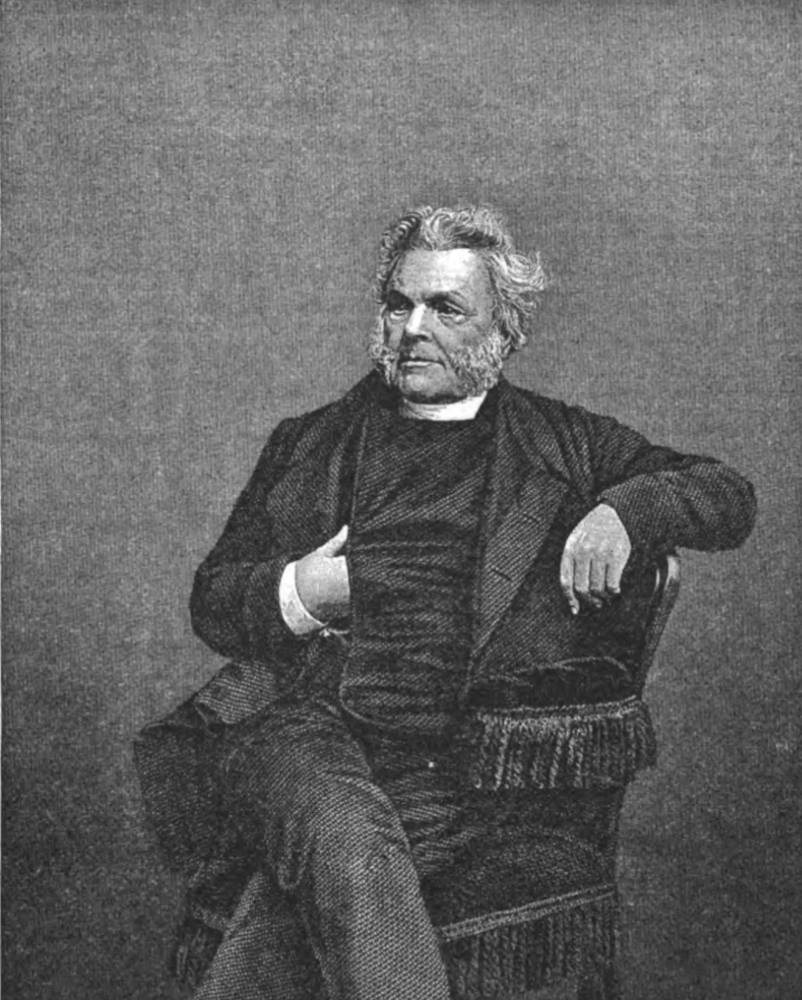

Statue of George Dawson, M.A., by F. J. Williamson.

During the short period he remained at this place of worship, Mr. Dawson gathered around him a large number of enthusiastic adherents, and when, in accordance with the provisions of the trust deed of the chapel, he found it incumbent upon him to withdraw from the pulpit, those who were in sympathy with his teaching withdrew with him, and resolved, at a meeting held at Mount Zion Chapel, February 23rd, 1846, to establish a new church, which should be unsectarian. The principles on which the ‘Church of the Saviour,’ as it was to be called, was established, were thus laid down by Mr. Dawson : “ That as a Catholic Church it is not their intention to have any doctrinal test as a church or as a congregation. They regard fixed views, embodied as professions of faith, as productive of mischief. The preacher should not be retained as an advocate Qf certain opinions. It is not the fair and manly mode, as all men differ; and no man has a right to judge another, further than by the Scriptural rule, * by their fruits ye shall know them.’ A man’s own conscience is the arbiter of his fitness to join the Church of God; more especially as they are known to differ in opinion. The preacher is to give the results of his study; and the people are not bound to believe him further than appears consistent to * v. xiv.f p. 222. themselves as inquirers after truth; their bond being a common end and purpose,—to clothe the naked, to feed the hungry, and to instruct the ignorant.”

The first turf on the site of the proposed church was turned on the 13th of July, 1846, and the building, which was situated in Edward Street, Parade, was completed and opened on the 8th of August, 1847. It was built from designs by Messrs. Bateman and Drury, and has a handsome portico entrance, under a bold arch, supported by columns of the Corinthian order. The further end of the chapel is semi-circular in form, and it is lighted from above through a panelled ceiling. Mr. Dawson’s discourses at the opening services were afterwards published, and entitled “The Demands of the Age on the Church.’” “The new ‘church,”’ says the writer just quoted, “was essentially eclectic, and while nonconformist as to polity, it borrowed anthems, chants, decorations, art, and celebrations from more orthodox sources. Special services at Christmas, on Good Friday, and harvest festivals were duly celebrated, and the example was soon followed in other places. Special organisations on novel lines were used for the education of children, and the care of the poor, with night classes for adults.” [Dictionary of National Biography, v. xiv., p. 222.]

Mr. Dawson also became famous as a lecturer, and took an active share in the educational, social, and political movements of the time. He became one of the ‘lions’ of the neighbourhood, and few strangers came to Birmingham without availing themselves of the opportunity of hearing the popular minister of the Church of the Saviour.

The Rev. John Angell James.

During the whole of the period under notice, the Rev. John Angell James continued in the pastorate of Carr’s Lane Meeting House. “As he approached the autumn of life,” says Elihu Burritt, “ his power in the pulpit became more perceptible and impressive. It was when the autumnal tints of those concluding years had touched his great bushy head and beard and strongly-marked features, that I first saw and heard him. The earnestness of his soul in his work, his voice, mellowed like a sabbath bell that had called a dozen generations to the sanctuary, the deep solemnity of his manner, the sheen of a godly life that seemed to surround him like a halo, the very reflection of the thoughts he had put forth upon the world through his books—all gave to his discourse a power which I had never seen equalled in any other minister on either side of the Atlantic.” [ Walks in the Black Country, p. 61]

When the second Independent congregation removed from the Union Meeting House in Livery Street to Ebenezer Chapel, a small remnant stayed behind and formed a third congregation of that communion. They worshipped in the old make-shift building, (which had been a playhouse, and subsequently the refuge of the burnt-out Unitarians in 1791), until 1845, when they built a handsome place of worship in Graham Street, which bears the name of Highbury Chapel. In that year the Rev. Brewin Grant became their minister.

A fourth Independent church was founded in 1825, when a half-finished chapel, which a few members of the Wesleyan body had commenced in Legge Street, was taken over and completed by the Independents. The Rev. P. Sibree became minister of this church in 1837.

Chapels were also erected by the Independents at Saltley, in 1828, at Wheeler Street, Lozells, in 1839, and at Palmer Street, in 1845.

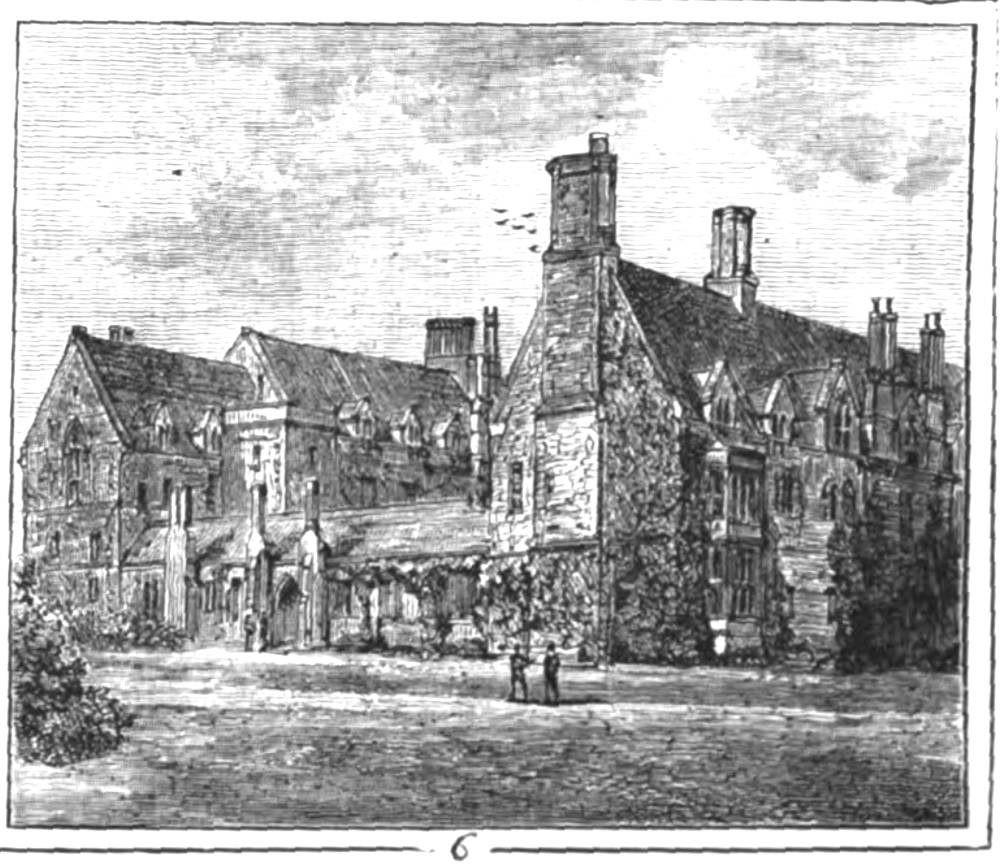

Springhill College . Source: The Graphic 10 (28 November 1874): 520.

One of the most important events in connection with this denomination during this period was the establishment of Spring Hill College for the education of young men for the ministry. This arose through the individual effort of one family who worshipped at Ebenezer Chapel, Steelhouse Lane. “Mrs. Glover and her sister, Miss Mansfield,” says Mr. J. A. James, “had been for many years members of the church in that place of worship, when their brother, the late George Storer Mansfield, Esq., came to reside with them. This gentleman was possessed of considerable landed property, as were his sisters also of property of other kinds. Reviewing in the latter part of his life, his former course, which had been that of a respectable country gentleman, but not of a real Christian, he was brought to see the importance, and to experience the power of religion. He then felt an anxious desire to do something in the way of glorifying God with that property which had hitherto been employed only for his own comfort and amusement, and wished to know in what way he could best accomplish this object. It was suggested to him by Mr. East, that it would be a useful appropriation of it if he founded a college for the education of young men for the Christian ministry. He approved of the plan, and gave some landed estates for the purpose. In addition, he, with his two sisters, Mrs. Glover and Miss Mansfield, set apart a considerable sum of money for the support of the institution. In order that the college might be established in their lives, Mrs. Glover and Miss Mansfield resigned their dwelling-house for this purpose, and the college was opened for the admission of students in 1838, when thirteen young men commenced their studies under the tuition of Mr. Watts, Professor of Theology and Ecclesiastical History, and Mr. Barker, Professor of Languages; to whom was shortly afterwards added Mr. Rogers, Professor of Mathematics, Philosophy, and the Belles Lettres.” Further notices of this Institution must be deferred to a later period in this history.

The Presbyterians

The Presbyterians do not appear to have prospered in Birmingham for some years after their migration from Graham Street to the smaller chapel in Newhall Street. Even the latter proved to be too large for them, and they erected a smaller one in Broad Street, in 1834. Prosperity, however, crowned their efforts in the new neighbourhood, and in 1848 they found it necessary to pull down the humble place of worship they had erected fourteen years before, and to build a large and handsome chapel in its place. The first stone was laid on the 25th of July, 1848, and it was opened on the 19th of September, 1849. The building was erected from designs by J. R. Botham, in the Italian style, and is surmounted by a lofty, but not very elegant tower. There are no windows visible on the external walls of the chapel, it being lighted from the roof, and this adds to the unattractive appearance of the building, as looked at from the outside. It was designed to accommodate nine hundred worshippers.

The Wesleyan Methodists

The Wesleyan Methodists, as the parent Methodist Society began to be called, built several new chapels during this period: one in Bristol Road in 1834, a second, ‘Wesley Chapel’ in Constitution Hill in 1838, and a third in Newtown Row in 1837, besides several smaller places at Summer Hill, Green Lanes, Small Heath, Balsall Heath, Nineveh, and other outlying districts. In 1836 Birmingham was recognised for the first time as a sufficiently important Methodistic centre to justify the holding of the annual conference of the connexion here. “To accommodate the four or five, or six hundred preachers, which now usually assemble at this great convocation, and remain together for three weeks, it required, it was supposed, a greater number of members of a certain standing in society than the body in this town contained. The trial was made, when it was found that, by the aid of Catholic spirited members of other orders of professing Christians, who kindly opened their houses to accommodate the preachers, the friends of Methodism in this town, though not equal either in numbers or in wealth to those of London, Manchester, Liverpool, Sheffield, Bristol, Leeds, or Hull, were not behind them in zealous and liberal attachment to their denomination, or in a generous ambition to have the honour of entertaining the Conference.”[J. A. James Protestant Nonconformity, pp. 208-9.]

In 1839 Methodism celebrated its centenary, and on the 25th and 28th of October in that year services and meetings in connection with this celebration were held in Birmingham. “ On the former of those days, which in conformity with the recommendation of the late conference, was devoted to religious services, public meetings for prayer were held in all the chapels, and the attendance upon those occasions was very numerous, the proceedings being conducted with great solemnity and devotion” [Artist's Gazette, October 28, 1839]. A Centenary fund was raised for various purposes in connection with Methodism, more particularly for the erection of a Wesleyan Centenary Hall and Mission House in London, and for the establishment of a second College (at Richmond) for the training of students for the ministry; and towards this fund the two Birmingham circuits contributed the sum of ^2,628 17s. 10d.

The other branches of Methodism also increased in numbers during this period. The Methodist New Connexion built a second chapel in Unett Street in 1838, and in 1842 this place of worship was considerably enlarged and improved. They also built other small chapels in Bridge Street and at Sparkbrook. The Wesleyan Methodist Association, a third offshoot from the parent society, established themselves in Birmingham, and built a chapel in Bath Street in 1839. The Primitive Methodists opened a chapel in Inge Street in 1831, and another in New John Street about 1849.

The Swedenborgians

A new place of worship was built by the Sweden-borgians in 1830, in Summer Lane, mainly through the exertions of the Rev. Edward Madeley, who had become their pastor in 1824. Under his guidance the church, which had for some years been divided, became once more united and energetic, and greatly increased in numbers and in influence.

The Countess of Huntindon’s Connexion

The Countess of Huntindon’s connexion in Birmingham found it necessary during this period, owing to the expiration of the lease of King Street meetinghouse (which had formerly been a play-house), to erect a new place of worship in Peck Lane. This was a neat Gothic building of brick and stone, but it was destined only to stand for a few years, as it stood on a portion of the site chosen for the central railway station, and was taken down to make way for that structure.

The Jews

The Jews appear to have prospered during this period. As will be remembered they had removed from the humble meeting-room in the Froggery in 1809, and erected a synagogue in Severn Street; but this had already proved too small, and had to be taken down in 1827, and a more commodious edifice was erected on the same site.

The Roman Catholics

The Roman Catholics who had been making great progress in and around Birmingham during the early years of the present century, undertook the erection of what was intended to be the great central cathedral of English Catholicism during this period. The Gazette of January 27th, 1834, made the following announcement in reference to this matter:

January 27, 1834.—It will be seen by a notice in this page that the practicability of erecting a Roman Catholic Cathedral in this town is under consideration. Dr. Walsh, Vicar Apostolic of the Midland district, presided at a meeting held in St. Peter’s Chapel, yesterday week, and various resolutions to that end were entered into. Among those who took part in the proceedings were the Rev. Messrs. M’Donnell and Peach, Messrs. Hardman, Tidmarsh, Palmer, Hopkins, Brien, Green, Boultbee, Bridge, Chambers, and Hansom—the latter of whom stated that he was sure they might set up a building which would outvie any place of worship in the town. The Right Rev. Chairman expressed his intention of giving £200 to the fund, and a monthly contribution of one pound towards payment of the interest of money to be borrowed. Mr. M’Donnell said he should put down his name for £20, and for half a sovereign per month until the building is completed. Other persons present also promised pecuniary assistance toward the object.

They chose as a site for the new cathedral that of the chapel of St. Chad, in Shadwell Street, which had been built in 1813, and having acquired additional land, extended the site to Bath Street, and designed the cathedral to front towards the latter street. The corner stone was blessed by the Rev. Dr. Walsh, assisted by Dr. (afterwards Cardinal) Wiseman, his coadjutor. Mr. Augustus Pugin supplied the designs for the cathedral, and he chose the Middle Pointed style for the building, which was finished in 1841 ; and on the 21 st of June in that year it was consecrated by Dr. Wiseman. On the 23rd of the same month it was formally opened with splendid ceremonial. The Archbishop of Treves, with the Bishops of Tournay and Chalons, and eleven other bishops, one hundred and twenty priests, and many of the Catholic nobility were present, and the bishops and clergy in rich vestments, attended by acolytes bearing lights and lilies, went in procession to the cathedral, where a solemn High Mass was celebrated.

The cathedral is built of red brick, with stone facings and dressings, after the example of many Continental Churches. The west end of the Church of St. Elizabeth, at Marburg, in Hesse-Cassel, seems to have given the idea of the west end of this. The length, including the porch, is 156 feet, and its width is 58 feet; the interior height is 75 feet. The nave is divided from the aisles by twelve clusters of pillars— six on each side—from the capitals of which a series of pointed arches spring completely up to the roof, without any break for a triforium or clerestory, thus forming the loftiest range of arches in the kingdom.

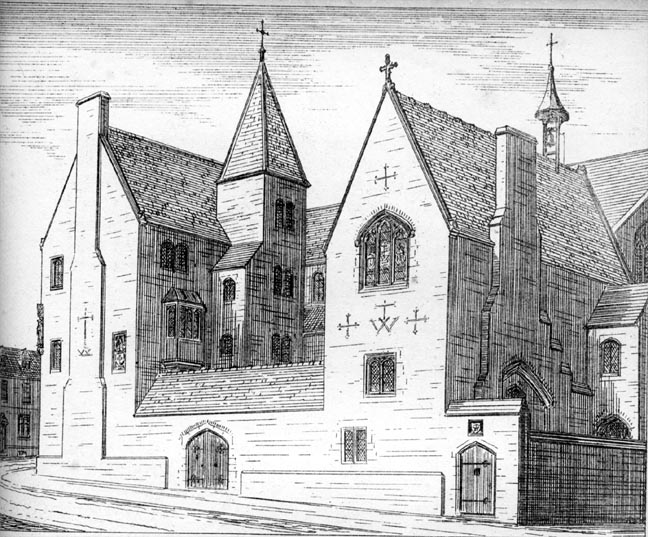

Rood Screen, Cathedral of St. Chad’s, Birmingham<>/span> by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852). Source: Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture

A handsome screen, surmounted by the Holy Rood, divides the choir from the nave, and a similar screen, but of a richer description, partitions off the Lady Chapel from the top of the north aisle. The windows in the choir and down the aisles, with the exception of those in the transepts, are long lancets, divided each into two bays; while the west window and the windows of the transepts are distributed each into six compartments, affording great facility for the introduction of stained glass. Some good specimens of this description are already to be found in the choir, representing ancient Saxon saints: in the Lady Chapel the Blessed Virgin stands in Glory, between St Cuthbert and St. Chad, and in the baptistry St. James, St Thomas, and St. Patrick are accompanied by groups representing the leading features of their history. The southern window represents, in beautiful groups, the life of St. Thomas of Canterbury, in honour of Canon Thomas Flanagan, late of this Cathedral: the northern window, which is the larger of the two, is a magnificent exposition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception, one compartment representing Pope Pius IX. surrounded by cardinals and bishops drawing up the definition: three lights of one side represent all the types of this doctrine contained in the Old Law, and the three lights on the other side their fulfilment in the New. The beauty of the groups, the harmony of colour, the lightness of the general effect, the number of texts of Scripture introduced, and the beading round the group of figures, which are all enclosed in Vesica-formed glories, make this window a masterpiece: it is a memorial in honour of the late John Hardman, Esq., of this town, a great benefactor of the cathedral.

Among the antiquities may be mentioned the pulpit, an elaborate carving in oak of the 16th century, representing the four Doctors of the Latin Church — St. Jerome, with the lion’s foot and thorn; St. Gregory the Great; St. Augustine, with the heart; and St. Ambrose—an episcopal throne and stalls of the 15th century, and a brass lectern of the same period. The pulpit is from the church of St. Gertrude at Louvain; the throne and stalls from the church of St. Maria in Capitolio at Cologne; the lectern, which was presented by the late John Hardman, Esq., is of splendid Gothic style, and of Flemish or German workmanship.

In 1876 a fine set of stations was erected on the walls, which consists of fourteen representations of Our Lord’s painful journey from Pilate’s house to Calvary; they are in bold relief and coloured in tints; they were cast by De Vriendt, of Antwerp. Beneath the cathedral is a crypt, or undercrypt, dedicated to St. Peter, and divided into separate chantries, which subserve the double purpose of oratories and burial places for the dead; besides the principal chantry or chapel, under which is a spacious vault for the clergy, four others are already fitted up, one (St. John the Evangelist) for Mr. Hardman’s family; another (St. James) for Mr. Waring’s; the third (St. John the Baptist) for Mr. Poncia; and the fourth for Mr. Fletcher’s family. There is mass in these chantries on the anniversaries, and public service in the crypt once or twice every week.” [Rev. W. Grkanky, Guide to St. Chad's Cathedral Church.]

Bishop's House, Birmingham/span> by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin (1812-1852). Source: Present State of Ecclesiastical Architecture

The bishop’s house was also erected at the same time as the cathedral, as a residence for the bishop and priests. It is, says Pugin, “a residence which, both in its ecclesiastical character and extent of accommodation, is in all respects suited for the occupation of the bishops and clergy, and also for transacting the increased business of the district, and has been erected for a sum which does not involve a greater annual outlay than would have been required for two large modern houses, which must have been destitute of every requisite for this important purpose.” In 1848 Birmingham became a see of the Roman Catholic Church, and on the 30th of August in that year, the Rev. Dr. Ullathorne was formally enthroned in St. Chad’s Cathedral as “Bishop of Birmingham.” Cardinal Wiseman, Dr. Newman, and other dignitaries of that church assisted at this ceremony, and in receiving the Papal rescript, which was read by the Rev. Dr. Weedall.

Dr. Walsh, who had been mainly instrumental in the erection of St. Chad’s Cathedral, died February 18th, 1849, and a fine monument was erected to his memory in the cathedral from designs by Mr. E. W. Pugin. “The figure of Bishop Walsh, in pontificals, with crozier and mitre, is in a recumbent posture. In front of the tomb are shields with the arms of the bishop, the cathedral, Oscott College, St. Edward the Confessor, and of Bishop Walsh (repeated). The tomb is surmounted by an elaborate canopy, the dossal diapered, and has a quatrefoil in the centre with a small figure of Bishop Walsh offering his Cathedral of St. Chad. The tomb is protected by an iron railing, with sconces for lights at the dirge on the bishop’s anniversary.” [W. Bates, Pictorial Guide to Birmingham.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Dent, Robert K. The Making of Birmingham: Being a History of the Rise & Growth of the Midland Metropolis. Birmingham: J. L. Allday, 1894. Birmingham: Hall and English, 1886. 398-403. HathiTrust online version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 4 October 2022.

Last modified 5 October 2022