[The following text and accompanying images come from the Internet Archive presentation of the 1903 issue pf The Studio, where this essay immediately follows A. L. Baldry's “James McNeill Whistler, His Art and Influence.” George P. Landow formatted and corrected the Internet Archive's generally clean text and arranged the images, some of which appear on separate facing pages in the original. Click on all images to enlarge them and to obtain additional information.]

How fascinating those were, the days when I lived with Whistler in the intimacy of his studio! And it was at the very best period of his life that I knew him — a period which is known as the "Maud' period. Yet at that time there was a good deal of fighting to be done. His position then was not what it is now. Now Whistler's pictures are recognised by everyone to be masterpieces, and Whistler himself a great master; but I can remember the time when scarcely a single critic of a single London paper failed to rail and jeer at him and his work. And some of the men about him — men who had been hypnotised by his overpowering personality, myself among the number — clubbed together and formed a little army, whose sole aim of existence was to fight Whistler's battles, and to place him, where he should be placed, far above the unbelieving Philistines and on a par with such men as Velasquez and Rembrandt. We called ourselves the "Whistler Followers." We were intensely in earnest: that was the best and the saddest thing about us. We were boiling over with enthusiasm. We thought of nothing else but Whistler. We talked of nothing else but Whistler. We lived for nothing else but Whistler. We had no time to do any actual work, our time was taken up in fighting for the master. In silence and in secret, and from a respectful distance the followers worshipped him. We felt that the master was in possession of tremendous secrets about art, but we never got within a certain crust of reserve and mystery in which he kept his real artistic self embedded.

Woman seated with hands in her lap

Still, this was as it should be. How could we suppose that one so great would readily reveal himself? We were very grateful to him for giving some of us, to a certain extent, the freedom of his studio. We used to steal in and furtively make sketches of his palette, and then meet to discuss the combinations of colour that he used. One of us found that he had been using black as a harmoniser, and that was so important a discovery that we called a general meeting at once to consider it. As a find it was tremendous, and so were its results. No matter how fair the subject, the tones must be harmonised with black. This was the master's secret. Certainly at this period we were all a little feverish, but I have no doubt that it did us a world of good. Our mistake was that we went to such extravagant extremes. For instance, there was a time when Whistler to reduce painting to a system, and kept in his tubes mixed colours such as "'flesh tone," "floor tone," "blue sky," and so on. We tried In carry this scheme a little further, and the result was — failure. And at last the climax came. One day I received a telegram from "follower," saying "Come at once. Important." I hurried to his home His wife met me in the hall and directed me to his studio;I noticed that she looked rather sad. As I mounted the stairs I heard a dripping sound and thought it must be the cistern, but the sound got louder and louder, and when I reached the top of the house I realised that it came from the studio itself. When I entered I found the "follower" at his easel and the model on the stand, and both of them surrounded by about fifty milk cans, from each of which hung long blobs of colour, and the floor was a mosaic of rings of coloured drippings. "Look at the simplicity of it," he cried, "we have been wasting our time mixing our tones on a palette: what we want is our tones already mixed and in proper quantities. Now just see here," he said, making a dash at the canvas with a brush out of the "lip milk can." I heard a drip, drip, but he was so excited that he did not realise that most of the "lip tone" was on the floor. "Now 'eye tone,'" he said, and made a dash at another milk can; this time the eye went, not on the floor, but into the background. I felt that the eye should be in the face somewhere, but still it was an eye, and it was art, and in art nothing mattered as long as you were reckless and had your tones. But, in spite of their eccentricities, the "followers" were very sincere in their worship of the master. They went shoulder to shoulder to fight for Whistler, and they were even prepared on an emergency to fight for him financially too with the few shillings they possessed. For instance, there was not one of us who would not have sold his last possession to buy a plate of Whistler's and destroy it rather than allow it to be handled unsympathetically.

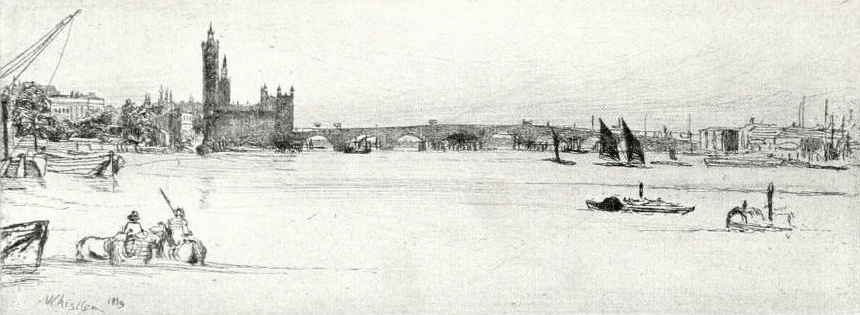

Westminster Bridge. Etching.

And it is strange now to meet at studios, as I often do, young painters who, having lately seen Whistler, will come up to one with all the master's little airs and graces, his straight-brimmed hat and long Noah's Ark coat, his parrot scream, and his "Ha, ha! Amazing," talking of the "intimacy of the studio " and all the old phrases that I have known for years. And these poor people who have perhaps never seen Whistler more than three times, and even on those occasions have been treated by him with more or less contempt, and made to fetch and carry, they will talk of being Whistler's pioneers, of having found the master. It is just as absurd to talk of "finding" Whistler as claiming to have discovered Wagner. Whistler is recognised by everyone to be a great master — recognised even by his enemies, those foolish people who in the early days strove to destroy him. And I say nothing, but I look at these little people and smile, and think of the real Fight that was fought and won fifteen years ago and more. I had the privilege of knowing Whistler more intimately than anyone at the particular period of which I speak. I was with him nearly every day: I was with him during that exciting time when he was made President of the Society of British Artists (now Royal). I saw that marvellous set of Venice etchings printed: in fact, the bulk of them were printed in my own printing-room, a room which I had especially arranged for the master, and it was in this little printing-room of mine that Whistler taught me the art of printing from the copper plate. This was my first insight into Whistler as a great master. And one of his characteristics as a master was that he would have perfection.

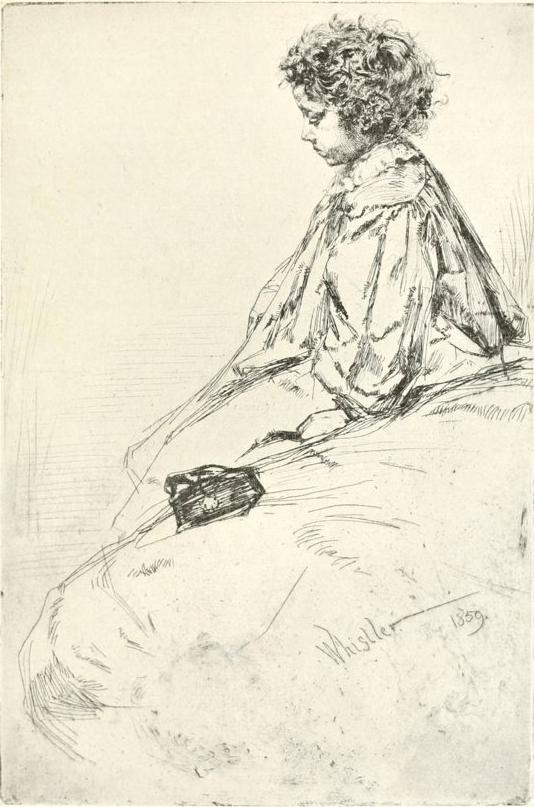

Left: The Beefsteak Club. Pen and ink. Right: Bibi Lalouette. Etching.

No matter how small the detail, it must be perfect. To begin with, he always insisted upon having old paper upon which to print his etchings, and preferably Dutch, because of a certain golden torn, unobtainable with new paper, which this particular kind gave to a proof. Many a time Whistler and I have spent weeks in Holland, poking about dirty little shops in search of old paper. And sometimes, after having discovered a fine collection of three or four thousand sheets, I have seen Whistler literally tremble with excitement, and scarcely know how to ask the price, lor joy. Then again he was very particular as to the choice of oil for mixing with the ink, also with regard to the temperature of the plate, the ure of the press, the i ondition of the blankets, and. in fact, everything had to be absolutely right. But when at length the proof was printed, I do not mind stating that the proof could not have been equalled by any other printer in the world. I must apologise for dwelling thus on the printing of an etching on the plea that Whistler himself attached such tremendous importance to it, and so loathed the work of the professional printer. And I feel the greater desire to touch on this topic because at the present time the market may be exploited at any moment with plates printed perhaps with gummy ink on vellum. Whistler loathed vellum and that varnishy ink which gives a glassy shine to a proof. My only prayer is, therefore, that these plates will be destroyed, and that the professional printer will never have the chance of mangling and marring their beauty.

On a Venetian Canal. Watercolor.

Whistler had his periods of painting as well as of etching. I remember those days well. Invariably, every morning, I received a letter saying, "Come at once. Important." On rushing round to his studio I found another letter directing me to a certain spot on the Embankment at Chelsea, and there the master would be working at, perhaps, a little shop with a few soiled children in the foreground. It might be a sweetstuff shop, and the children standing with their faces glued to the pane. Perhaps, if one of them appealed to Whistler from the decorative standpoint he would say, "Not bad, Menpes, eh?" This was, perhaps, a very grubby little person indeed. But Whistler would take her kindly by the hand and the three of us would trot along to ask the mother if she might sit, the child with its upturned face gazing with perfect confidence at Whistler. And the master would talk to that little guttersnipe in such a charming intimate way about his work and aspirations! "Now we are going to do great things together," he would say, and the little dirty-faced child blinking up at him seemed almost to understand. For Whistler never failed with children; no one understood them quite like the master, and no one depicted child life better than he. Whistler's children were never little old ladies; they were real children, with all the grace and ingenuousness of childhood apparent in every line, he would explain to this child his entire scheme for the work, and together we would go back to the studio where, perhaps, the little one would help to set the table for lunch, settling down at once to full responsibility, for Whistler in some ways was very helpless. Then she would sit, and Whistler would paint — sometimes a lifesized oil-colour, sometimes a little pastel. But from the moment his brush touched the canvas, the child as a child was forgotten, and she might droop and faint before Whistler would come down to earth again and understand that this was a living, breathing mortal. Sometimes after a long afternoon the little girl began to bellow, something was hurting her or she was stiff with standing so long, and Whistler, looking up with a start, would say, "Pshaw: What's it all about? Can't you give it something, Menpes — can't you buy it something?" And the child eventually left the studio laden with toys, and perfectly happy once more. In the afternoon the master was in the habit of drifting out into the open with a packet of copperplates, which I always kept carefully ground and ready for his use. And suddenly finding a subject he would etch a little plate. Then, perhaps, right in the middle of our work he would rush oft to a garden party. And it often annoyed me that Whistler, the great master, should be wasting his time with foolish, ignorant people, who neither understood nor appreciated his worth. In the evening we would often dine together at the Arts Club, or else at a friend's house, for Whistler's friends at that time were my friends and he always liked to have me with him. We invariably went home at night by way of the Embankment to look at a certain nocturne, perhaps a fish-shop, which Whistler was trying to commit to memory. He would talk aloud as he created the idea for one of his marvellous pictures. He would say, "Look at that golden interior with the two spots of light, and that old woman with the chequered see the warm purple tone outside going away up to the green tone of the sky, and the shadows from the windows thrown on the ground — what an exquisite lacework they form! "He would say all this aloud, and I would walk back with him to his studio and talk with him sometimes until two in the morning. And then he would say as I was leaving, " Now, Menpes, remember; I want you to be here early in the morning. As for me, I am going to make my mind a blank until I paint that fish-shop; and you must be here early." And I always was there early — so early that I very often breakfasted with Whistler. And he would paint his pictures without a single note, for he maintained that if he drew on the spot it only handicapped him.

Two studies in the style of Albert Moore. Left: Three-quarter rear view of woman leaning on parapet. Pen and ink. Right: Woman leaning against a parapet. Etching.

We used often to take little journeys together, Whistler and I. I remember once going to St. Ives in connection with a series of pictures for an exhibition that Whistler was to hold in Bond Street. We stayed for some weeks in a small apartment kept by an old lady whom Whistler was very anxious to please. A painter happened to be travelling with us, a man who had once been an actor, touring in the provinces, and who knew St. Ives well. He completely won over the landlady by presents of fish, which he was in the habit of buying from the fishermen and presenting to her. Whistler was annoyed by these gifts, which were continually being brought home; they got on his nerves. "Why don't they give me fish?" he said. "I ought to have fish." One day Whistler was out painting a shop — I remember the shop well, because I was bold enough to paint the same one at the same time, standing about twenty yards away from him. Suddenly I heard a puffing and a blowing, and looking up I saw two men coming towards us carrying suspended from a pole an enormous fish, a great flat thing about the size of a dining-room table. Whistler saw it, too, and at once remembered the actor — painter and was inspired to buy the creature for the landlady. "Hey, stop!" he shouted. "How much for the fish ? I'll give you half-a-crown." "Right you are," said the men, and they promptly laid the fish down on the ground, pocketed the money and went off. I pretended to ignore Whistler, the fish, and the whole transaction. "I say, Menpes," he shouted to me, "they have accepted it." It was all so sudden. Whistler had paid the half-crown, the fishermen had laid the fish down and disappeared all in the space of a few seconds. Whistler kept calling me to come, but I dared not approach him; I was convulsed with laughter. Here was this enormous flat fish and Whistler circling round and round, daintily probing it with his long cane and trying to find which way up it was, for the creature looked the same all round. And when I could steady myself a little, I asked him what he was doing. "Which, Menpes," he said -"which should you imagine was his chest?" It was impossible to tell; and I went on with my work and Whistler with his, and we left the fish on the pavement and never referred to it again.

A Little Sea-Piece. Watercolor.

There was always plenty of incident when Whistler travelled. I once went on a journey to Brussels with him. And I never have had such a journey before or since. It was full of incident. Directly he set his foot on board everyone was working for him; he made them all interested, tewards, sailors, captain, passengers — everyone. He had to sleep in a four berth cabin, which was full, and Whistler occupied an upper berth. I knew directly I saw that cabin-load that was going to be trouble. Whistler made me wait until he was settled before I retired to my own quarters next door. But I had left him no longer than ten minutes when he screamed out to me : "Menpes! Menpes!" I got up and opened the door. "Menpes," said Whistler, "there is a person in here occupying the whole of the floor." I looked down and saw a poor man disrobing, who certainly was occupying a great deal of space. But then he was extremely stout. After a few minutes' conversation I extorted from him a promise that he would retire in half-an-hour, and left Whistler somewhat pacified. I imagined that now things would go well. But it was not to be. Later on in the night, when everyone had dropped off into their first sleep save Whistler, the door began to bang. It had been left unlatched, and though the night was a perfect one there was just enough motion to swing it to and fro, and every few minutes it went bang. This very soon got on Whistler's nerves, so he put on his eyeglass and gripped his cane, which he always kept by him, and began to probe the stout gentleman underneath. After a good deal of probing he awoke. "Did you hear that?" said Whistler, in a mysterious tone of voice. "There it goes again — flip, flap." And very soon he had awakened all the occupants of the cabin that they might hear the noise. Then the stout gentleman began to explain that he thought it must be the door which, being unlatched, was allowed to swing, and what it really needed was to be fastened. "Well," said Whistler, "you seem to know all about it; how would it be for you to get up and latch it?" And, of course, in the end the poor old gentleman was made to get out of bed and fasten the door. And so it continued the whole night through. There was incident throughout the voyage. And it was interesting the next morning to watch the different people coming out of the cabin, for it was only too apparent by the expression on their faces that they had suffered. The stout gentleman emerged in rather a hurry, as though propelled against his will by some hidden force in the rear: he was muttering to himself and shaking his fists. But Whistler came out as fresh as champagne, sparkling and dainty ; he had slept well, he told me, and had enjoyed the night thoroughly, especially as the cabin was cleared so early of its occupants.

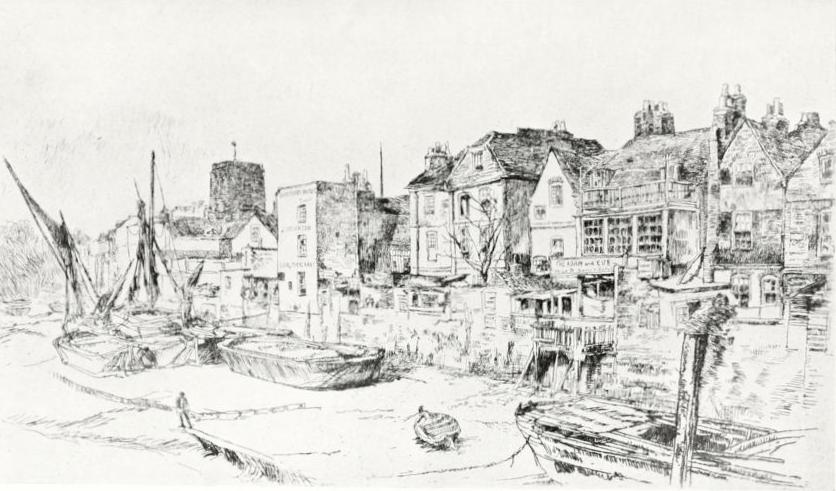

Adam and Eve, Old Chelsea. Etching.

Those days which I spent with Whistler were fascinating beyond words, and at the same time a superb education for me. Whistler allowed me to paint with him at times, and not only did he help me in my work but he taught me many important lessons, and ones that I never shall forget. For instance, he taught me what was meant by artistic placing and balance. Indeed. Whistler very rarely placed his butterfly on a picture without first asking me, "Now, Menpes, where do you think the butterfly is going this time?" It used to be a little joke between us. and after some months of habit I was invariably able to put my finger on the spot where the butterfly should be placed to create the balance of the picture. I worshipped Whistler in those days, and I worship him still. The greatest regret of my life is that there should have been a little rift within the lute, but that blemish on an otherwise perfect friendship is quite forgotten now, and I remember only the old days, the glorious days when we lived together, worked together, and thought together. And the name of Whistler conjures up in my mind a host of pleasant memories which, as time goes on, will never fade or grow less.

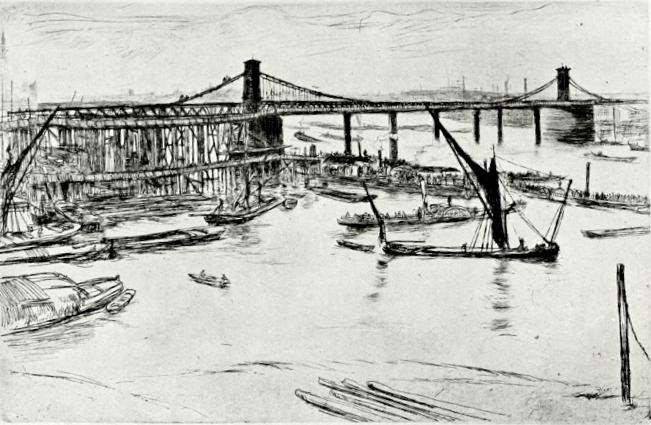

Old Hungerford Bridge. Etching.

References

Menpes, Dorothy. “Reminiscences of Whistler by Mortimer Menpes.” The Studio 29 (1903): 245-57. Internet Archive. Web. 12 January 2012.

Last modified 12 January 2012