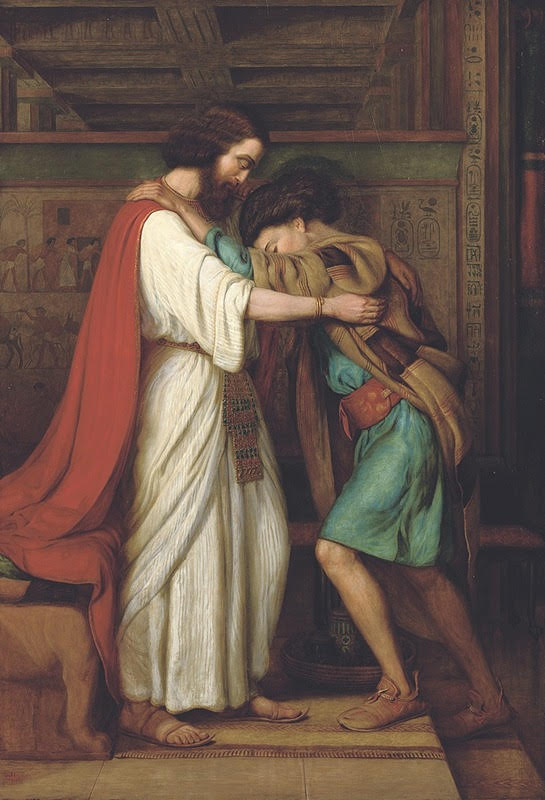

Pharaoh and Joseph, by William J. Webb(e) (1830-1912[?]). 1865. Oil on panel. 36 x 25 inches (91.5 x 63.5). Private collection, image courtesy of Christie’s. Not to be downloaded; right click disabled.

The subject portrayed in this painting has proved to be contentious because it once sold at Christie’s, London on 7 March 1896 as Return of the Prodigal. This controversy was discussed in detail when it later sold at Christie’s in 2008:

The scene portrayed in this picture, and its exhibition history, have proved elusive. Initially it was thought to depict the return of the prodigal son, but the figure to the right looks too kempt for someone cast amongst swine. A possible clue comes in the hieroglyphs behind the figure to the left. These depict corn being harvested and stored by Egyptians. Could the figures then represent Pharaoh, rising from his throne, and Joseph, in his coat of many colours? Joseph had interpreted Pharoah's dream of seven lean cattle devouring seven thin ones, and seven thin ears of corn devouring seven fat ones as a premonition that seven years of plenty would be followed by seven years of famine. To prevent hardship, grain was harvested and stored in readiness and Joseph became Pharaoh's chief steward. The episode was taken to prefigure Christ's feeding of the five thousand. [140]

The problem with entitling this work Pharaoh and Joseph is that the figure on the left doesn’t really have the appearance of an Egyptian pharaoh as normally depicted in Victorian art. He appears bareheaded with long hair and a long beard and is not wearing the most common headgear seen in sculptures and wall paintings of pharaohs, a headcloth called a Nemes, that frequently showed a rearing cobra in the middle, symbolic of his divine kingship. Sometimes a pharaoh is depicted wearing either a white domed crown called a hedjet, the symbol of Upper Egypt, or the deshret crown, the symbol of Lower Egypt, or a crown that combined features of the two. Pharaoh was also frequently shown clean shaven or wearing the false beard symbolic of his connection to Osiris. Although richly clothed in a white robe and red cloak he doesn’t display the regalia of a royal figure, the crook and the flail. It also seems unusual for a pharaoh to be embracing his servant, even if Joseph did protect Egypt against a severe famine and become Pharaoh’s overseer. Certainly this scene would make much more sense as a depiction of The Return of the Prodigal were it not for the wall mural with the Egyptian scene and the Egyptian hieroglyphs in the background. The true subject of this work therefore remains unknown unless it possibly refers to some obscure biblical episode that so far has eluded scholars.

Christie’s has also pointed out that in this work there is a marked similarity in style and subject matter to that of the painter William Gale. Gale had paid the first of his two visits to the Holy Land in 1862, the same year Webb(e) was in Jerusalem. It is possible that they either met at this time or were even travelling companions. Both had studios at Langham Chambers in London and both exhibited at the same venues so there is little doubt that the two must have been at least known to each other if not friends. Their Orientalist works have much in common, especially their “pot boilers” of attractive young Arab women models, like Webb(e)’s An Arab Gleaner and Gale’s An Arab Woman or An Arab Girl.

Bibliography

Victorian and Traditionalist Pictures. London: Christie’s (8 June 2008): lot 55, 140-41.

Created 1 June 2025