Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower, 1857. Oil on panel, 24 x 29½ inches (61 x 75 cm) Principal version, private collection.

Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower was painted in 1857, soon after Wallis’s two Pre-Raphaelite masterpieces Chatterton and The Stonebreaker. The principal version was exhibited the Royal Academy in 1858. This picture has much in common with these previous two paintings in that it retains its Pre-Raphaelite qualities of “truth to nature.” It is highly detailed and finished in its handling, with the vibrant colours for which Wallis was known.

It was obviously based on a great deal of research in order to insure historical accuracy in its details. Early in his career Wallis concentrated on historical paintings and episodes from the life of Sir Walter Raleigh were one of Wallis’s particular favourite subjects. Other such works he painted included Gondomar witnessing the execution of Sir Walter Raleigh of 1861 and Sir Walter Raleigh in Durham House of 1862. Wallis may have been influenced by the renewed interest in Raleigh following the publication by T. Nelson and Sons in 1853 of the massive biography Life of Sir Walter Raleigh by Patrick Fraser Tytler. On the other hand Wallis may simply just have had a lifelong interest in this illustrious figure from British history. There is doubt that he was drawn to the Elizabethan period.

[Click on images to enlarge them.]

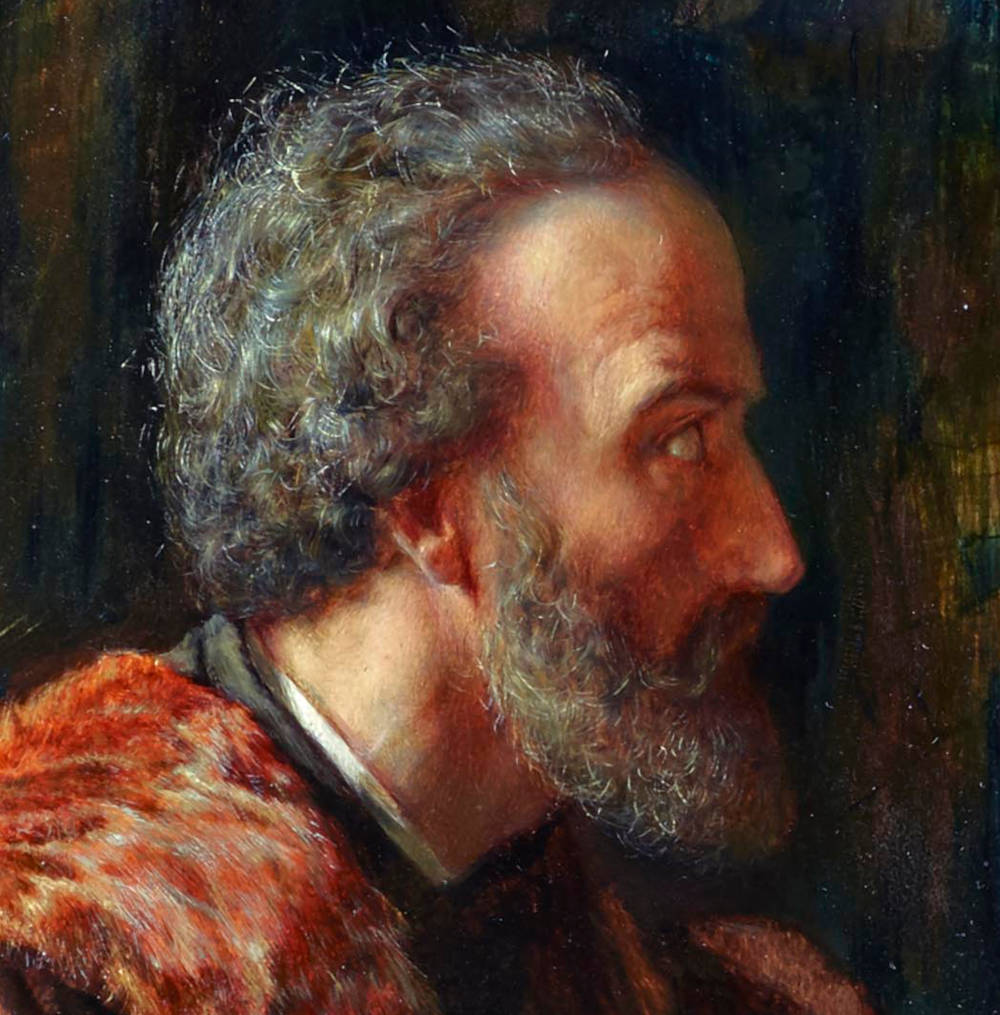

Sir Walter Raleigh (1552-1618) was an adventurer, explorer, and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I whose portrait is shown at the top left of the painting. When Elizabeth died in 1603, Raleigh was accused of plotting to depose James I and was sentenced to death and imprisoned in the Tower of London. The sentence was reduced to life imprisonment. Raleigh was well treated, however, and his family was allowed to join him in a large apartment. Upon being freed in 1616, he again sought the fabled gold of El Dorado in Guyana, but violated James’s strict instructions to avoid attacking the Spanish colonists in the area. After his return, he was rearrested and, at the request of the Spanish ambassador, Raleigh's death sentence was re-instated. He was beheaded on October 29, 1618.

The Painting’s Composition and Iconography

In this work Wallis again utilizes the type of compositional structure he had previously used successfully in pictures like Dr. Johnson at Cave’s, the publisher and The Death of Chatterton and then again in Henry Martin in Chepstow Castle and Sir Walter Raleigh in Durham House. In all these pictures figure(s) are contained within a flat foreground space and with distant landscapes visible through a window in the background. This device allowed Wallis to create a distant background without having to make the traditional middle-ground transition between it and the foreground. In Chatterton the tower of St Paul’s can be visualized in the background while in Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower the church spires of All Hallow by the Tower, St Margaret Pattens, and St. Olave can be seen.

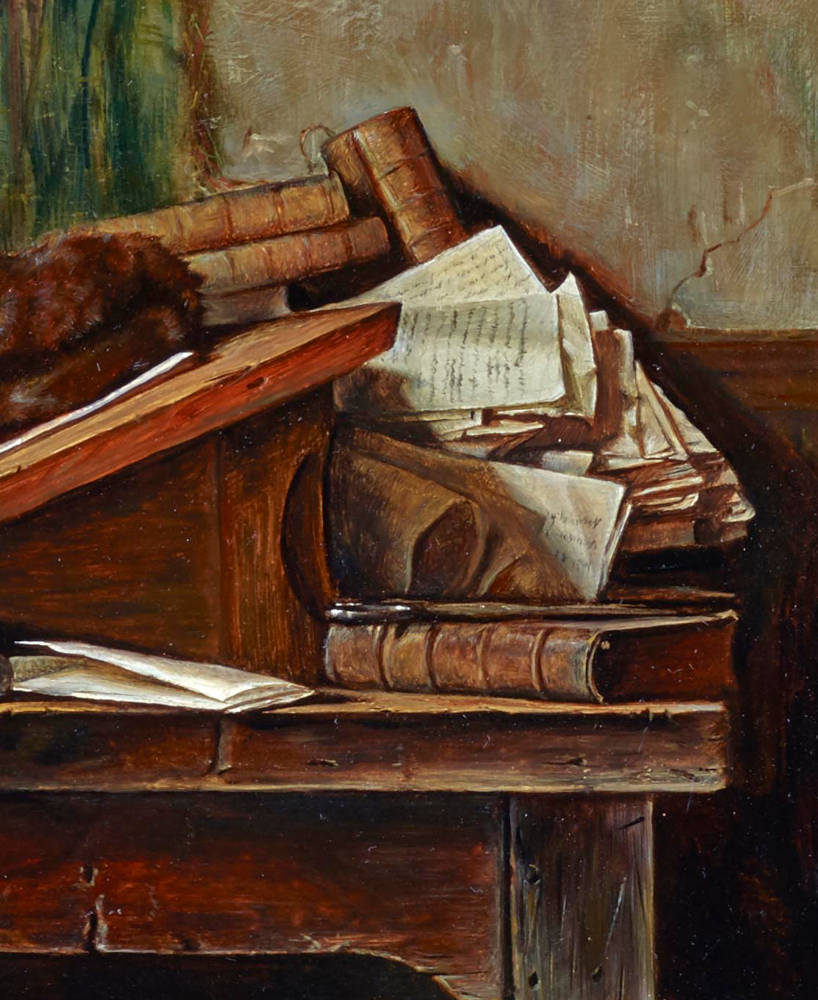

Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower is filled with the symbolic references Pre-Raphaelite painters loved to include, as has been pointed out by Greenhalgh (8-11). The globe in the left foreground refers to Raleigh’s many voyages of discovery. A pipe sitting on the globe refers to the commonly held belief that Raleigh was the first to introduce tobacco to England. The vase of wilting flowers on the window ledge is symbolic of his upcoming execution. In the language of flowers poppies symbolize sleep and death, foxgloves are symbolic of pride and ambition, while love-in-a–mist (nigella damascena) can symbolize love and relationship bonds. A sprig of ivy adorns the frame of Queen Elizabeth I’s portrait, symbolizing the fidelity Raleigh felt for her even after her death. On the wall is hung Raleigh’s sword scarf of the gallant man, now covered with cobwebs from long disuse. A large map of Guiana and the surrounding region has been hung on the wall in the background. Guiana was the destination of Raleigh’s first voyage to try to discover El Dorado in 1595.

Mary Ellen Meredith and the Biographical Context of the Painting

The year 1857, when Wallis was working on Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower, was a difficult time for him because he was in the midst of his notorious affair with Mary Ellen Meredith, who had left her marriage to author George Meredith to be with her lover. In the summer of 1857 the two had travelled together throughout Wales and their son Harold was likely conceived during this trip. The couple returned home in September 1857 but chose not to live together, perhaps fearful of widening the scandal. An accusation of discreditable behaviour against Wallis would hardly have been helpful towards furthering his position in the art world of the time. We know from a letter that in October 1857 Wallis left Tintern, where he had been working on Henry Marten in Chepstow Tower, another history picture he exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1858, and took the train to Clifton to spend time with Mary Ellen. Wallis appears to have divided his time between working on paintings in London and visiting Mary Ellen at Elm Cottage, Redland, near Clifton where she spent most of the final six months of her pregnancy. At that time Wallis was living at 198 Marylebone Road in London, which is confirmed by writing on the back of the Raleigh painting. Their son Harold was born on April 18, 1858. It is obvious, therefore, that the time when Wallis was working on his painting of Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower must have been a very stressful and emotionally trying time for him.

Versions of the Painting

There are three known versions of Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower all in private collections. The major version had been lost for many years and only recently resurfaced with the dealer Martin Beisley Fine Art, London, in 2020. The second version of the picture is either a smaller copy, or a highly finished oil sketch, that sold at Rupert Toovey Auctions in 2009. The third version is a watercolour, which is unusual in Wallis’s oeuvre. While early in his career it was common for Wallis to do oil sketches for, or smaller oil version of, his more popular paintings, a watercolour version was most atypical, unlike some Victorian painters such as Millais.

The Painting’s Reception

The principal version of the picture received mixed reviews when it was shown at the Royal Academy in 1858, no. 369. The Royal Academy Review gave it faint praise reporting that the work was

the least objectionable picture exhibited this year by Mr. Wallis. The subject is a poor one, but portions of the painting are very good. A frowzy old man is sitting at a table, contemplating a little boy opposite him, who is coiled up in an arm chair, and blowing an impossible bubble. To people who are not well up in dates, it would be rather difficult to ascertain whether the old man or the little boy was intended for Sir Walter. Mr. Wallis has possibly foreseen the fact of this uncertainty arising, and he has, therefore, introduced near the old man, a Milo pipe to assist the public in arriving at a conclusion upon the matter. [20]

The critic for The Athenaeum remarked:

Mr. Wallis is not very successful this year…Sir W. Raleigh in the Tower (369), though only a historical anecdote, is more interesting, though we hardly knew him again in fur and gown, looking so old and seedy and musty, seated at a table with stock books and other philosophic implements. We rejoice in the thoughtless boy in slashed purple satin (fine contrast to his father's tawny bilious yellow) lounging on a chair and blowing bubbles, - glittering many-coloured evanescences, types of life. There is a sober thoughtfulness about this as there is about all Mr. Wallis does, an unaffected vigorous intensity: but this year he is unlucky in subjects. [567]

The reviewer for The Art Journal questioned the reason for the inclusion of the boy in the picture:

Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower, circa A.D. 1600, H. Wallis. This was about the commencement of his long imprisonment. We find him busied with his History of the World confined in a room presumed to be over the Water Gate. He is represented by a dignified and sadly thoughtful figure, seated with his back to the light, and opposite to him is a little boy, amusing himself by blowing bubbles. The impersonation is round and palpable, and the head is endowed with expression and argument. The room is furnished with a taste which discriminates between that which should be conceded and that which should be withheld; and what is made available here is most appropriate, and just sufficient. But Raleigh’s best companion in his incarceration would have been the wife whom he so dearly cherished. The child blowing bubbles means something or nothing: if he means nothing, he ought not to be there; if it be intended to point a derisive allusion to Raleigh’s works, on the authority of Ben Jonson and the author of ‘Curiosities of Literature,’ the unbecoming satire has visited an occasion worthy of an elevated sentiment. [167]

Isaac Disraeli (1766-1848) was an English writer whose best-known work was a collection of essays entitled Curiosities of Literature, which contained anecdotes about historical persons and events. In this book Disraeli impugned Raleigh’s claim that his Historie of the World was a work of his own hand, as the Elizabethan playwright Ben Jonson had done earlier. It is difficult to ascertain for certain whom the child is in the painting but Wallis must have included him for a reason. There are two likely possibilities for the boy - Raleigh’s own son Walter (Wat) or King James’s son Prince Henry Stuart (1594-1612). In the painting Raleigh is shown working on his Historie of the World which he may have started as early as 1603 - in which case either boy would have been the right age to have served as the subject of the boy blowing bubbles. Certainly Prince Henry is known to have held Raleigh in high esteem and because the book was intended as an instructional tool for the prince this certainly makes him a likely candidate. At the same time, however, it is known that Raleigh’s family were allowed to visit him in the Tower so it could be young Walter (1593-1618) who is portrayed. Contemporary paintings of Prince Henry or of Walter are not particularly helpful in narrowing down the identity of the boy since for once Wallis’s inclination to search for historical sources seems to have deserted him! Neither of the two boys looks particularly like the boy in Wallis’s picture. The key must surely be with the symbolism of the boy blowing bubbles, which must be meant to convey a message of some sort, likely representing the fragility of life. Prince Henry was the first of the two boys to die, aged only eighteen, in 1612 from typhoid fever. Wat also died young on Raleigh’s ill-fated second mission to find El Dorado in 1618, again preceding the death of his father.

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

“The Royal Academy.” The Art Journal, New Series IV (1858): 161-72.

“Fine Arts. Royal Academy.” The Athenaeum, No. 1592 (May 1, 1858): 565-67.

Lanigan, Dennis T. and Deborah Greenhalgh. Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower, c.A.D.1600. London: Martin Beisley Fine Art, 2021.

Lessens, Ronald and Dennis T. Lanigan. Henry Wallis. From Pre-Raphaelite Painter to Collector/Connoisseur. Woodbridge: ACC Art Books, 2019, cat. nos. 29 & 30, 100-01.

The Council of Four. “A Guide to the Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Arts.” The Royal Academy Review, London: Thomas F. A. Day, 1858.

Last modified 17 October 2022