This article had been arranged and formatted for our website by George P. Landow, and was later checked and put online, together with its illustrations, by Jacqueline Banerjee.

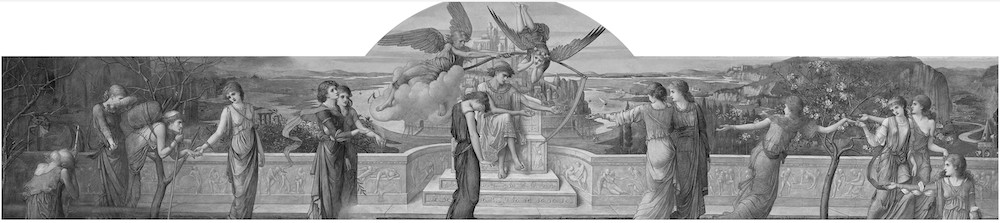

Strudwick's Passing Days, p. 97. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

It cannot be said that we are suffering at present from any dearth of persons able to draw and paint. Even in the old Academic days, when drawing and painting were as painful and unwholesome as tight-lacing, and much more difficult, there were always plenty of men who could master them. But now that "naturalism" has sanctioned the comparatively easy, healthy, and congenial practice of representing the things we see as we see them, and accepted that end as a justification of the means in all cases, technical skill that once would have seemed prodigious is becoming commonplace. It is the same in all the arts. Violinists who have sat at the leader's desk in famous orchestras for twenty years are eclipsed by girl students; lads in the crudest imitative stage compose "symphonic poems" in which the orchestra is handled with a resource of which Cherubini had no conception; pianists from the Weimar school learn enough in two years to put out of countenance their elders who drudged for ten over Czerny and Clementi; in literature the advance is so enormous that the press is kept going by unskilled hands and casuals, who yet turn out more readable work than the experts of the Delane and Tom Taylor period; minor poets are expected to versify better than Pope or Byron; the mere routine of architecture transmogrifies our shops and villas past recognition; and our Art students, after a couple of seasons in Paris, return with a technique which gives them but too good ground for deriding many of our Royal Academicians as obsolete bunglers. When one thinks of how tempting the artistic professions appear to young people who hate business (small blame to them under existing conditions), and who have neither aptitude, diligence, nor means to qualify them as doctors or lawyers, it is appalling to see the ease with which a highly plausible degree of executive power can be developed in the hands of persons who may, nevertheless, have no more real vocation for pictorial art than a circus horse has for dancing. In that case, when they take up painting as a profession, they are only good handicraftsmen spoiled. Fill the next Academy with their works, and no doubt a considerable advance on the present standard of execution will be the result. It does not follow in the least that the proportion of true pictures to wasted canvases will be raised a single fraction. The spring forward from the workmanship of a quarter of a century ago to that of to-day is certainly tremendous. But so is the fact vouched for by Sir Joseph Whitworth, that — a good Nottingham lace machine will turn out as much work as was formerly done by 8,000 women. Both have about equal bearing on our prospects of laying up treasure in pictorial art. Exhibitions of triumphs of execution are no doubt more interesting than the exhibitions of failures of execution which are the usual alternative; but when the triumphs owe their force and brilliancy to their very independence of the purpose of all artistic execution, that is, the production of pictures, then the interest they engage is the same as that appealed to by exhibitions of improvements, not in machines, but in machinery. In the end, all this execution for execution's sake — abstract execution, so to speak — becomes insufferably wearisome; and its professors, finding abstract execution unsaleable, get driven into portrait painting of the cleverest mechanical kind.

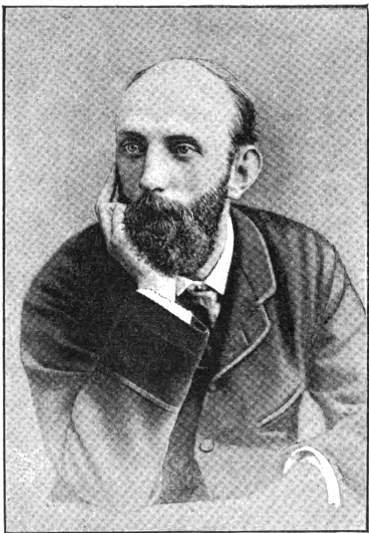

Portrait of J.M. Strudwick, p. 97.

Now true pictorial execution — that which is only called into action as a means to materialise a picture conceived by a true creative artist, never looks like abstract execution. It differs not only for better or worse, but in kind. The adept in the one may be incapable of the other. I cannot say that I have ever heard a man say, "I can draw; I can paint; I can hit off values to a demi-semi-tone; but I cannot make a picture"; for persons so accomplished are seldom, if ever, conscious that their displays are not pictures. But the first time I ever spoke to the subject of this article, a true maker of pictures if ever there was one, he, no doubt concluding that I was a fancier of abstract execution, and being unwilling to disappoint me, informed me in an apologetic way that he could not draw—never could. This was neither mock modesty nor genuine modesty. It was not modesty at all: it was simply a piece of information which was, in a certain sense, quite true. I firmly believe that Strudwick could no more draw, except as a necessary incident in the production of his pictures, than he could eat without appetite. Doubtless the feat would be physically possible: he could do it if a pistol were held to his head; but the result would have none of that expression of enjoyment in the feat as a feat — none of that triumph in the power to perform it, which carries our clever executants over their subjectless canvases, and nerves the professional oystereater to empty his hundredth shell with unabated excitement and hope.

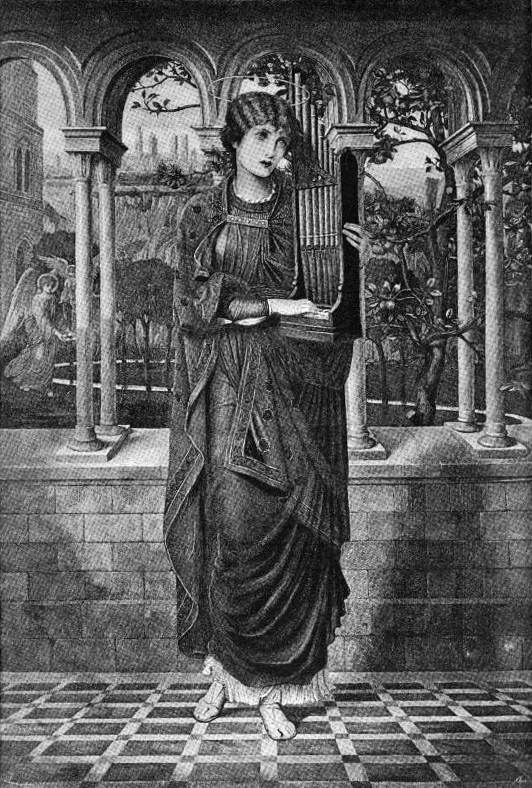

Strudwick's St Cecilia, p. 99. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

This sort of incapacity is a priceless gift to a painter when he has finished his novitiate; but to the student it is so disadvantageous and discouraging that its possessor cannot feel otherwise than ashamed and diffident until the pictures come to justify it. Even then the habit of mind persists; and the maker of the true picture will expect you to disparage him because he did not, and could not, turn out one of those barren tours de force of which you are deadly tired. And this expectation will be fulfilled so often in the case of the professional critic, that even when the painter's constantly growing sense of the pre-eminent worth of the order of genius which is attended by such incapacity has deepened to a full and serene conviction, he still remains conscious of the great improbability of any acquaintance or critic having attained to that wisdom. And so, though at last void of all misgiving, and perfect in his faith, he continues to gently warn expectant visitors not to cherish expectations which he would now be very sorry to gratify. This, I believe, was the secret of Strudwick's attitude of apparent self-depreciation. Rightly understood, it was one of pure pity for me. Had I misunderstood it, and said pretty things of his work just to encourage him (privately not thinking much of it), no doubt I should have benefited by the fine social qualities of the painter, and escaped without a word or look to make me conscious that I was making a donkey of myself. It was impossible to consider the likelihood of such escapes occurring often without furtively looking to see whether his face had yet acquired an habitually sardonic expression. But Strudwick, if he laughs at all — and he has too fine a sense of humour to keep his countenance entirely — knows how to laugh in his sleeve, as the following sketch of his life will show.

He was born at Clapham in 1849, and was educated under Canon Boger at St. Saviour's Grammar School, which he left at sixteen and a half with honourable mention for proficiency in the primitive drawing then taught in the establishment, but otherwise undistinguished and undecorated. It was proposed, as usual, that he should enter an office and learn business; but he was so clear on the point of having no vocation for commerce, and indeed of vehemently detesting it, that his family, much perplexed at his unreasonable prejudice, had to seek some other solution. His own views dated from certain hours of his boyhood during which he had played at being a painter in the studio of the late Elijah Walton, with whom his people were acquainted. That sort of life, he thought, would meet his case exactly. So, since he would do nothing else, and could at any rate urge that drawing was the only thing he had ever beaten his competitors at, he was sent to South Kensington. As long as he had only to draw freehand scrolls in the elementary room there, he got on well enough; but when he reached the point of qualifying himself for admission to the antique room by one of those highly finished crayon studies which have done so much to make the official English Art curriculum ridiculous, he was hopelessly unable to comply with such a demand for "abstract execution." What was more, he felt that his impotence in this respect was incorrigible, and that if the antique room was to be attained at all, some other means must be found. One day, accordingly, he and a fellow student, who was equally impatient of chalk and breadcrumb, adventurously walked as of right into the upper division, and succeeded in seeming so perfectly at home there that nobody demanded their credentials. The next step was promotion to the Academy Schools; and for this chalk studies were again required, and unlawful entering was quite impracticable. It now occurred to Strudwick that the difficulty of the crayon work depended a good deal on the scale of the drawing, and that if he only went to work on a sufficiently colossal scale, he might pass muster. He accordingly chalked out a prodigious fighting gladiator — a "whacker," as he himself describes it; but Mr. Redgrave refused to recommend the evasive designer to Trafalgar Square. Strudwick, seeing that he had nothing to hope from professional judgment, bethought him that, by the constitution of the Royal Academy, students might be recommended by any citizen of ascertained professional status. He accordingly appealed to a friendly clergyman, who answered his purpose quite as well as Mr. Redgrave. The usual Academy course followed; and the novice set himself resolutely to attain the academic distinction to which he had certainly not, so far, established any claim. He competed for the "Life" medal, for the "Historical" medal, and every other prize that came in his way; and he was invariably highly unsuccessful. The only encouragement he received was from John Pettie, who discerned some colour sense in him, and occasionally asked him to his studio. Out of this arose the most desperate of all Strudwick's enterprises, no less than an attempt, long persevered in, to acquire the Pettie technique, with its brilliant colour and slashing brushwork. It is quite unnecessary to say what the upshot of this was.

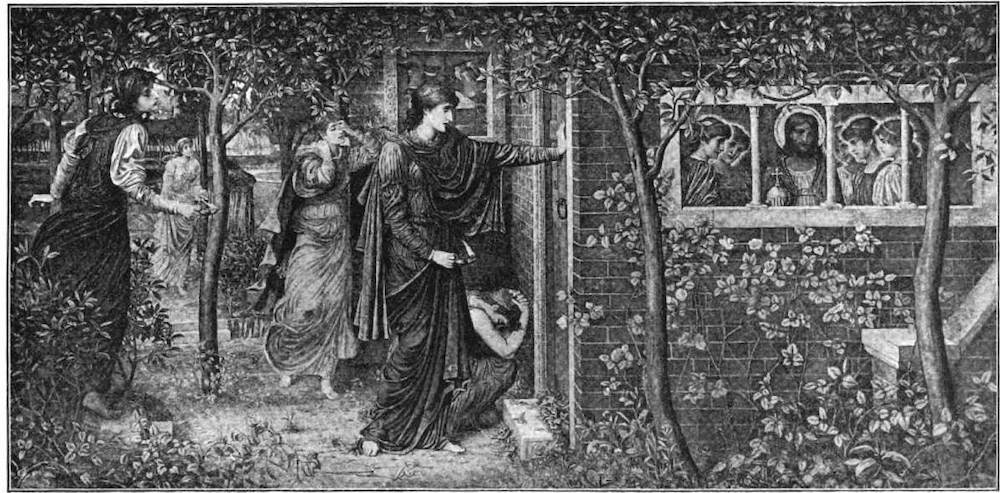

Strudwick's The Ten Virgins, p. 100. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Strudwick was now a convicted failure. He had no excuse left for believing, or asking others to believe, that he could acquire a technique, or win gold medals, or even get beyond an elementary class-room by legitimate means. Under these circumstances there was nothing left for him to attempt except the painting of a picture; and this feat, which has baulked many a gold medallist, he achieved without any hitch. The Academy rejected the work. He sent it again; and they rejected it again. He kept on sending it until they found a place for it. Meanwhile — for each of these trials cost a year—he had exhibited at the Dudley Gallery; sold a potboiler or two, which exemplified his efforts in the splashy style; and finally got into regular employment in the studio of Mr. Spencer Stanhope, and subsequently of Mr. Burne-Jones, where he did such work as a painter of established reputation may have done for him without suspicion of keeping a "ghost." Then Lord Southesk bought the Academy picture for sixty guineas, and wrote to the painter in terms which showed that he, at least, was convinced that he was dealing with a real painter. Strudwick promptly hired a studio for himself; and since that time his vocation as an artist has never been challenged. There is no such thing in existence as an unsold picture by Strudwick; and so the story of his early struggles may be said to end here. It sufficiently explains the man as he appears now, charitably offering you the South Kensington view of himself as hopelessly deficient in skill, resource, and judgment; and offering it with a sincerity partly due to his having been imposed on by it during his most impressionable years, and partly, of course, to its being so far true that he, no more than Michael Angelo or any one else, has as much skill, resource, or judgment as he would like to have. But you have only to take him at this valuation, as you may easily do if you happen to be a bad judge of a man, and a worse one of a picture, to find that you are dealing with one of the most obstinate characters in creation. He has wide, altogether extra-"professional" views; and he defends them with extraordinary tenacity, not on the dogmatic ground that they are right, but from a conviction that they are the only possible views for him. As to the true relation between his own opinion of current Art or contemporary social life and the conventional pedantries and follies on these subjects, or between his own work and the ordinary Bond Street ware, it does not take long to discover that he is not the least in the dark on either ground. Anybody with a quick eye for facial expression will detect even in the portrait given here a certain humorous sense of his real conclusions in the now celebrated case formerly adjudicated upon at South Kensington and Burlington House.

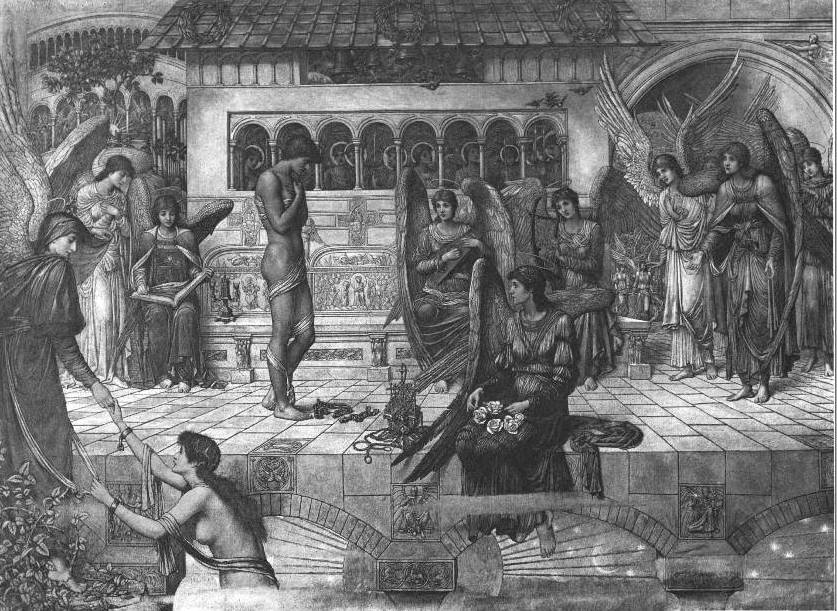

Strudwick's The Rampart of God's House, facing p. 97. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The pictures reproduced are all in the collection of Mr. W. Imrie, of Liverpool, to whose courtesy we are indebted for their appearance in these pages. The execution of these easel pictures is smooth, and the method of representation simply drawing on the flat surface and colouring it: Holbein, Hogarth, Bellini were not more exact and straightforward than Strudwick. The pictures are finished up to the point at which further elaboration would add nothing to the artistic value of the picture; and there the work stops, not a stroke being wasted. Thus a typical Strudwick is not "finished" as a typical Meissonier is; but it costs more pains to produce. No matter how minutely a painter copies a model in the costume of a certain period, with appropriate furniture and accessories, his labour is as nothing compared to that of the man who creates his figures and invents all the circumstances and accessories. This is what Strudwick does. For instance, the censer in 'The Ramparts of God's House' is not to be purchased in Wardour Street, nor the angels' dresses hired in Bow Street, nor the sculptured marble seat copied at the Musee Cluny, nor the heads found on the shoulders of any living model. And not only are these pictures entirely invented, they are also exhaustively thought out, an important part in their excellence; for a painter may be so hasty and superficial in snatching at the first image his imagination offers him as to make one regret that he did not stick to the usual plan of painting some likely young woman of his acquaintance, and labelling her as one of Shakespeare's heroines. The conception tion of the Strudwick picture is as exhaustive as the execution; and this is what makes it so thorough and impressive. You sometimes remember a Strudwick better than you remember even a Burne-Jones of the same year.

Two remarkable examples of Strudwick's power of finding subjects for his pictures are here reproduced. In 'Passing Days' a man sits watching the periods of his life pass in procession from the future into the past. He stretches out his hands to the bygone years of his youth at the prompting of Love; but Time interposes the blade of his scythe between them; and the passing hour covers her face and weeps bitterly. The burdened years of age are helped by the strength of those that go before; and then comes a year which foresees death and shrinks from it, though the last year, which death overtakes, has lost all thought of it. As a pictorial poem, this subject could hardly be surpassed; and it is not unlikely that it will be painted again and again by different hands. Indeed, the painter himself has recurred to it, though with an entirely new treatment, in 'A Golden Thread,' purchased for the public under the Chantrey Bequest in 1885. In 'The Ramparts of God's House' a man stands on the threshold of Heaven, with his earthly shackles, newly broken, lying where they have just dropped, at his feet. The subject of the picture is not the incident of the man's arrival, but the emotion with which he finds himself in that place, and with which he is welcomed by the angels. The foremost of the two stepping out from the gate to meet him is indeed angelic in her ineffable tenderness and loveliness: the expression of this group, heightened by its relation to the man, is so vivid, so intense, so beautiful that one wonders how this sordid nineteenth century of ours could have such dreams, and realize them in its art. Transcendant expressiveness is the moving quality in all Strudwick's works; and persons who are fully sensitive to it will take almost as a matter of course the charm of the architecture, the bits of landscape, the elaborately beautiful foliage, the ornamental accessories of all sorts, which would distinguish them even in a gallery of early Italian painting. He has been accused of imitating the men of that period, especially one painter, whose works are only to be seen in Italy, whither he has never travelled. But there is nothing of the fourteenth century about his work except that depth of feeling and passion for beauty which are common property for all who are fortunate enough to inherit them.

Strudwick's 'Thy tuneful strings wake memories', p. 101. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

In colour these pictures are rich but quietly pitched and exceedingly harmonious. They are full of subdued but glowinglight; and there are no murky shadows or masses of treacly brown and black anywhere. As to screwing up his palette to the ordinary exhibition key, and thereby unfitting his pictures to hang anywhere except in an exhibition with every other canvas there at concert pitch, he has always cheerfully allowed his pictures to take their chance of being glared out of countenance in the Grosvenor or the New Gallery sooner than play any varnishing-day tricks with them. As he progresses, and his scheme of colour becomes subtler and more comprehensive, it gets rather lower in tone than higher, although his design becomes broader, and shows signs of that evolution which is most familiarly exemplified by the growth of Perugino's style in the hands of Raphael. It is impossible to foresee what sort of work Strudwick will be turning out ten years and twenty-five years hence; and this article, therefore, may as well stop here as make any pretence of completeness. But it may at least be said that some of the fruits of Strudwick's first manner are so beautiful that any change must involve loss as well as gain.

Bibliography

Shaw, George Bernard. "J.M. Strudwick." Art Journal, 1891: 97-101. Internet Archive. Web. 8 April 2014.

Created 8 April 2014

Last modified 27 September 2025