For intensity of nature all round my old friend Frederic Shields had no equal in my large circle of friends. I never knew a brain so active, so keen, so wearing. He was so sympathetic that I never knew him to be without some kind of agony or other in all our forty years of close friendship. A poor boy, a youthful period of semistarvation and uncongenial work, he emerged through it all to a remarkable exaltation of life, and at last got the chance of doing the work he loved. Shields' early life was spent entirely among workfolk for the most part very poor. He was a Ragged School teacher; he sketched, not only the misery but the constant humour and what beauty he could find around him. A notable series of book illustrations to a "Rachda' Chap's Visit to the "Great Exhibition" of 1851 is full of keen observation and mother wit. For bread-and-butter subsistence he did a great number of domestic and street subjects, most of them of great charm. Red chalk and watercolour were then his media.

Ordsall Hall (1825) by James.

He lived, when he could afford, in old houses in the midst of great gardens, for any kind of noise wrecked him. I knew him first in the old timbered house "Ordsall Hall," a remarkable "magpie" relic of the sixteenth century. Many a fine time we had in the quiet evenings there. He would bring out his books of engravings of old and fine work, and tell me all about the why and the wherefore of their qualities, and show me why they endured.

About 1874 he left Manchester for London, intending to devote himself solely to sacred subjects. He was fully possessed with the idea that God had given him his rare gift to be devoted to that alone. In his last great work he fully believed that his Maker would bear him up till the series was completed. He did live, to the surprise of all of us, to finish his exalted task, and then, after a year of acute suffering, he left us at the ripe age of seventy-eight. How he had lived so keenly for so long a time was a puzzle to all who knew him. The slightest outside noise tortured him, and he had a lifelong battle with street organs, bands neighbours' cocks and hens, and indeed with all the strange worries of what he called "devilisation." Yet he could not live out of it all, for he was not only sympathetic with every phase of humanity, but wanted all of it as material for his work. He was a constant, a very rapid worker. He has left thousands of studies, some of them masterpieces. In fact, it must be said that Shields was too diffuse, too analytical : his larger work is overlaid with detail, his symbolism is profuse and over-subtle ; it is carried much too far in detail, resulting in confusion to the beholder. His finest faculties were not sufficiently in leash. Rigorous selection he had, but his mind was so full, so active, it led him to redundance where quietude was the one essential needed. We all used to say that, like Walter Crane, he had more inventive power than a whole Royal Academy. . . .

His studio at Merton was in the centre of a fine old garden, and there he was always glad to see his friends. He was a wonderfully vivid and picturesque talker.

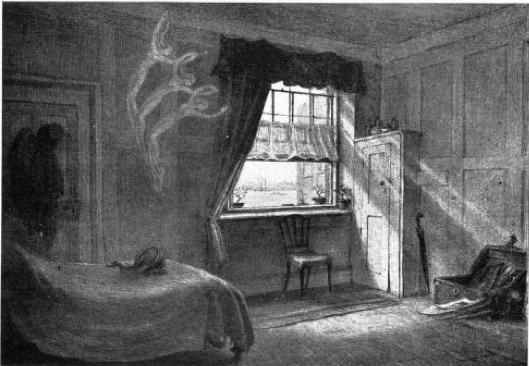

William Blake's work-room and death-room by Frederic Shields.

Shields, along with D. G. Rossetti, was a great student and admirer of the genius of William Blake. For the second edition of Gilchrist's "Life of Blake" he sought out the humble tenement in Fountain Court, Strand, where Blake lived, worked, and died. He made a characteristic drawing, which I possess. One evening he took it to Cheyne Walk to show to Rossetti, and next morning received this sonnet upon it:

William Blake.

(To Frederic Shields, on his sketch of Blake's work-room and death-room, 3, Fountain Court, Strand.)

This is the place. Even here the dauntless soul.

The unflinching hand, wrought on; till in that nook.

As on that very bed, his life partook

New birth, and passed. Yon river's dusky shoal,

Whereto the close-built coiling lanes unroll,

Faced his work-window, whence his eyes would stare.

Thought-wandering, unto nought that met them there.

But to the unfettered, irreversible goal.

This cupboard. Holy of Holies, held the cloud

Of his soul writ and limned ; this other one.

His true wife's charge, full oft to their abode

Yielded for daily bread the martyr's stone,

Ere yet their food might be that Bread alone.

The words now home-speech of the mouth of God." [83-89]

References

Rowley, Charles. Fifty Years of Work without Wages. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1911. University of California at Los Angeles copy made available online by Internet Archive. Web. 9 November 2012.

Last modified 9 November 2012