he theme of the woman destroyed by love -- betrayed by unrequited love, seduced by false ideals or false lovers or victimized by tragic love -- dominated Pre-Raphaelite, as well as Victorian, paintings and poems of the nineteenth century. Bound with the Victorian idea of feminine weakness, the Pre-Raphaelite concept of the woman as a victim stems from themes of medieval romance. However, there always remains an element of unfulfilled desire or denial of the true sweetness of romantic love. The Pre-Raphaelites re-interpret this idea and focus on the sensuality and sexual frustration or punishment of the female -- ideas that were met with both fear and fascination by most Victorians. Their works also re-fashioned this theme to include an awareness of social injustices. Most Victorian works depicted the woman alone, left to bear the brunt of shared sexual transgressions and cast out into the uncaring world. However, many Pre-Raphaelite paintings and poems include the male's presence or allude to his role in her destruction. The weight of blame shifts as we are asked to consider who has wronged the woman? And furthermore, does the nature of her destruction justify her final fate?

he theme of the woman destroyed by love -- betrayed by unrequited love, seduced by false ideals or false lovers or victimized by tragic love -- dominated Pre-Raphaelite, as well as Victorian, paintings and poems of the nineteenth century. Bound with the Victorian idea of feminine weakness, the Pre-Raphaelite concept of the woman as a victim stems from themes of medieval romance. However, there always remains an element of unfulfilled desire or denial of the true sweetness of romantic love. The Pre-Raphaelites re-interpret this idea and focus on the sensuality and sexual frustration or punishment of the female -- ideas that were met with both fear and fascination by most Victorians. Their works also re-fashioned this theme to include an awareness of social injustices. Most Victorian works depicted the woman alone, left to bear the brunt of shared sexual transgressions and cast out into the uncaring world. However, many Pre-Raphaelite paintings and poems include the male's presence or allude to his role in her destruction. The weight of blame shifts as we are asked to consider who has wronged the woman? And furthermore, does the nature of her destruction justify her final fate?

The Pre-Raphaelites depicted the woman destroyed by various forms of love, whether unrequited, tragic or adulterous, by highlighting not only her mental destruction but also focusing on her sexual frustration or punishment. The Victorians believed passion to be deviant; thoughts of sexuality would cause insanity and thus repression was necessary. With the strong societal enforcement of these beliefs, many Victorians lived with great shame, guilt, and fear of damnation (Walkowitz). Pre-Raphaelite works with themes of sexual morality often emphasized the woman's sexual frustration or her punishment, which stemmed from her sexually deviant behavior; for it was often considered unthinkable that a woman would have sexual thoughts or desires.

Eventually destroyed by unrequited love, Mariana, the disconsolate heroine of Tennyson's lyric "Mariana," waits in vain for her lover. In his painting of the same title, John Everett Millais introduces Mariana (1851) in a sensuous stretching pose, which breaks from the typical pose of the woman inwardly expressing her grief. Painted with her arms bent and resting on the back of her hips as her head tilts back, Mariana's posture reveals the desolation and impatience that result from her intense longing. The changing leaves outside her window reflect her withering away and also emphasize her imprisonment. As Martin Meisel points out, the stained-glass window depicting the Annunciation and the stylized animal and floral motifs on the wall behind her, separate Mariana from the natural world of life outside. The improvised altar table with candles and triptych also helps suggest the withdrawn, isolated life one associates with a nun (Nelson, Victorian Web). Emblematic of the artificiality of her existence without human contact or love, Mariana's surroundings embody her role as a martyr for love. The Tennyson epigraph that accompanies the painting: "'My life is dreary -- / He cometh not' she said;/ She said, 'I am aweary, aweary -- I would that I were dead'" also conveys Mariana's physically and emotionally wounded state, destroyed by admitting her sexual desires and realizing their futility.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Paolo & Francesca (1855) reworks the tragic tale of the love affair that results in their deaths by emphasizing the lustful and sexual nature of the lovers' union. Painted in triptych form, the first frame shows the two figures in an embrace, moved to consummate their illicit love by the story of Lancelot and Guenevere resting in front of them (Liverpool). The soft glowing light, warm tones and tender treatment of the scene illustrates the amorous force that leads to their end. The poets Dante and Virgil, depicted in the center frame, are accompanied by an inscription which quotes Dante's exclamation: "Alas! How many sweet thoughts, how much desire, led them to this unhappy pass" (Liverpool). They watch the tragic lovers swept in the flaming winds of the Second Circle of Hell, in the furthest frame, as punishment for their adulterous love. Despite its forbidden nature, Francesca's love for Paolo softens her punishment and seems to survive even in Hell, further demonstrating its power. Floating, with their arms wrapped around one another in a tight embrace, their figures appear content and serene in their punishment. Unlike Augustus Egg's triptych, the artist does not use Francesca to demonstrate the immorality of adultery. Instead, Rossetti portrays the sensuality of her tragic love and seems to suggest that their love lies beyond condemnation.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's Paolo & Francesca (1855) reworks the tragic tale of the love affair that results in their deaths by emphasizing the lustful and sexual nature of the lovers' union. Painted in triptych form, the first frame shows the two figures in an embrace, moved to consummate their illicit love by the story of Lancelot and Guenevere resting in front of them (Liverpool). The soft glowing light, warm tones and tender treatment of the scene illustrates the amorous force that leads to their end. The poets Dante and Virgil, depicted in the center frame, are accompanied by an inscription which quotes Dante's exclamation: "Alas! How many sweet thoughts, how much desire, led them to this unhappy pass" (Liverpool). They watch the tragic lovers swept in the flaming winds of the Second Circle of Hell, in the furthest frame, as punishment for their adulterous love. Despite its forbidden nature, Francesca's love for Paolo softens her punishment and seems to survive even in Hell, further demonstrating its power. Floating, with their arms wrapped around one another in a tight embrace, their figures appear content and serene in their punishment. Unlike Augustus Egg's triptych, the artist does not use Francesca to demonstrate the immorality of adultery. Instead, Rossetti portrays the sensuality of her tragic love and seems to suggest that their love lies beyond condemnation.

With his poem "The Defence of Guenevere," William Morris reinterprets the Arthurian legend of Guenevere, a popular source of Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood work. In a speech resembling the dramatic monologues of Robert Browning, Morris creates a realistic drama confronting the illicit romantic passion between the Queen and Sir Launcelot. Earlier in the poem, Guenevere associates herself with the innocence of springtime to elicit sympathy from her audience. However, she later describes the sensual nature of their love in passionate tones, recalling:

Wherewith we kissed in meeting that spring day,

I scarce dare talk of the remember'd bliss,

When both our mouths went wandering in one way,

And aching sorely, met among the leaves;

Our hands being left behind strained far away. [lines 134-138]

Utilizing sensual, almost erotic, descriptive language, Morris's Guenevere refuses to remain "stone-cold for ever" and brazenly presents and defends her sexuality. Understood as a woman guilty of any sort of sexual activity out of wedlock, the fallen woman was equated with a woman's sexual self-destruction. By stressing her passion and desire, Morris's Guenevere attempts to renounce the shame and guilt associated with adultery; however, she must still suffer for her actions. Saved from her initial death sentence and cast out of Arthur's Kingdom, "King Arthur's Tomb" tells of her self-inflicted vow to devote herself to Christ instead of returning to Lancelot.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's poem "Jenny" (1870) features the prostitute, commonly referred to as the "great social evil" in the Victorian period. According to Judity Walkowitz, at least 80,000 prostitutes worked in central London in the last quarter of the 19th century (Walkowitz). Rossetti's "Jenny" highlights the sexual asymmetry inherent to her profession. In lines 1-9, the narrator describes:

Lazy laughing languid Jenny,

Fond of a kiss and fond of a guinea . . .

Fair Jenny mine, the thoughtless queen

Of kisses which the blush between

Could hardly make much daintier.

If one trusts the speaker with his description, "languid" and "thoughtless" Jenny does not appear bothered by her own circumstances. While she remains a symbol of a ruined woman, seduced by the physical, Jenny also becomes a desiring sexual subject in her own right. While the speaker condemns her for being impure, he wrestles with his simultaneous compassion for the prostitute and passion for the woman. Less about the fate of the young prostitute than about the inner life of the narrator, "Jenny" reveals the character of the prostitute who does not see the error in her ways and perhaps even enjoys her sexual freedom.

Generally depicted as a solitary figure, the victimized woman represented by many Victorian artists bore the burden of her destruction alone. Whether her undoing involved an unrequited romance or shared sexual transgressions, she often faced the uncaring world as an outcast -- punished as a mad woman or social misfit. Many Victorian works aimed to incite pathos and offered didactic instructions in order to avoid a similar fate. However, several Pre-Raphaelite artists and writers and their contemporaries, such as Richard Redgrave, sought to alter this traditional depiction to include an awareness of social injustices -- often alluding to the fact that in every ruined woman's story there lay a guilty man.

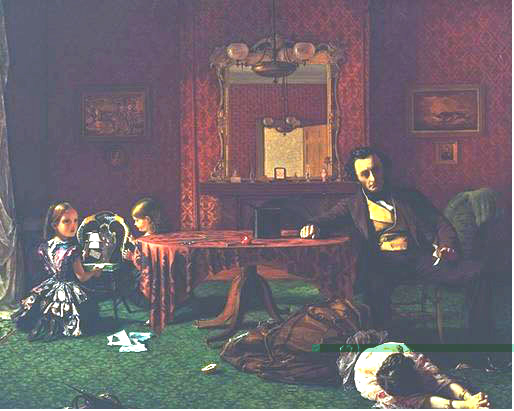

Left: The Outcast by Richard Redgrave

Right: The Infidelity Discovered by Augustus Egg

A popular example, Outcast by Richard Redgrave embodies the Victorian puritanical attitude toward sexuality. A melodramatic painting, Redgrave depicts a stern father casting out his daughter and her illegitimate baby into the literal cold, while the rest of the family weeps, pleads, or beats the wall with excessive emotion. The artist focuses on the grim fate that awaits the outcast woman in order to warn other young ladies to avoid similar temptation and ruin. On the floor lies what appears to be the incriminating letter, but her partner in crime remains absent from the scene. Augustus Egg's Past and Present series depicts a woman's infidelity to her husband and the dire consequences in three dramatic and theatrical scenes. The first, The Infidelity Discovered, shows the fallen woman's body thrown at the feet of her husband, who has just discovered her deed. Her prostrate body points to the door, indicating her outcast status and forced removal from the family (Edelstein 205). Elements of the comfortable and happy life that the woman has supposedly ruined are represented by the lavish living room and the children at play in the corner.

Left: The Abandoned Daughters by Augustus Egg

Right: The Wife Abandoned By Her Lover With Her Bastard Child by Augustus Egg

The second and third paintings, The Abandoned Daughters and The Wife Abandoned By Her Lover With Her Bastard Child, continue the dark story by illustrating the consequences of her actions and their self-destructive effects. The forlorn daughters, consoling each other by the window, and their fallen mother, huddling under a bridge, turn their respective heads to the same moon which becomes the sole connecting focal point of each piece. The only mention of the guilty man in this story remains in the first scene, as a small picture crushed under the husband's heel -- a minute detail easily overlooked. The quotation accompanying the series: "August 4th - have just heard that B -- - has been dead more than a fortnight, so his poor children have now lost both parents. I hear she was seen on Friday last near the Strand, evidently without a place to lay her head. What a fall hers has been!" also fails to acknowledge the existence of her accomplice; focusing the blame solely on the disloyal female (Edelstein 209).

Conversely, the very presence of the male speaker in D. G. Rossetti's "Jenny" demonstrates the male's direct role in the fallen woman's destruction. The fact that the narrator speaks from inside the prostitute's bedroom emphasizes his personal role in perpetuating Jenny's situation, which he considers briefly in his dialogue. The reader realizes that while he sits, questioning her purity, Jenny symbolically epitomizes his own fallen nature. Holman Hunt's The Awakening Conscience also comments on this society by including the direct presence of the guilty male. Hunt's painting shows a kept mistress at the moment of her realization. She rises from her position on the man's lap and judging from his expression, he does not seem to be aware of her sudden consciousness. Captured during mid-song, his arm across her waist restricts the woman's movement and beckons her to sit back down. On the painting's frame Hunt placed a motto from Proverbs: "As he who taketh away a garment in cold weather, so is he who singeth songs unto a heavy heart." These words criticize her unfeeling seducer, who remains unaware how his words have oppressed and aided her conscience (Landow, Victorian Web). Both works include a heightened awareness of social injustices in the adulterous affair's traditional gender roles and challenges and disperses the idea of blame.

Conversely, the very presence of the male speaker in D. G. Rossetti's "Jenny" demonstrates the male's direct role in the fallen woman's destruction. The fact that the narrator speaks from inside the prostitute's bedroom emphasizes his personal role in perpetuating Jenny's situation, which he considers briefly in his dialogue. The reader realizes that while he sits, questioning her purity, Jenny symbolically epitomizes his own fallen nature. Holman Hunt's The Awakening Conscience also comments on this society by including the direct presence of the guilty male. Hunt's painting shows a kept mistress at the moment of her realization. She rises from her position on the man's lap and judging from his expression, he does not seem to be aware of her sudden consciousness. Captured during mid-song, his arm across her waist restricts the woman's movement and beckons her to sit back down. On the painting's frame Hunt placed a motto from Proverbs: "As he who taketh away a garment in cold weather, so is he who singeth songs unto a heavy heart." These words criticize her unfeeling seducer, who remains unaware how his words have oppressed and aided her conscience (Landow, Victorian Web). Both works include a heightened awareness of social injustices in the adulterous affair's traditional gender roles and challenges and disperses the idea of blame.

In Take Your Son Sir (1852), Ford Madox Brown confronts the theme of the fallen woman with a focus on the illegitimate child, making the shared sexual nature of the woman's transgression explicit. The idea of the illegitimate child and the fact that the adulterous woman could try to pass off this child as her husband's true offspring frightened Victorian society. In the double standard for husbands and wives, it was unthinkable that a woman would be unfaithful to her husband, but it was understood that a man might (Nochlin 139). As the title indicates, Brown's woman thrusts forward the offspring of an illicit union to the father's outstretched hands, reflected in the mirror. Her confrontational pose and defiant expression seems to demand shared responsibility for the child. The artist underscores the presence of the guilty man by placing the viewer of the painting in the role of the perpetrator. In a traditional scene showing the fallen woman and child, instead of displaying the typical Victorian shame and guilt, the woman seems to shows pride and challenges the viewer to confront the situation.

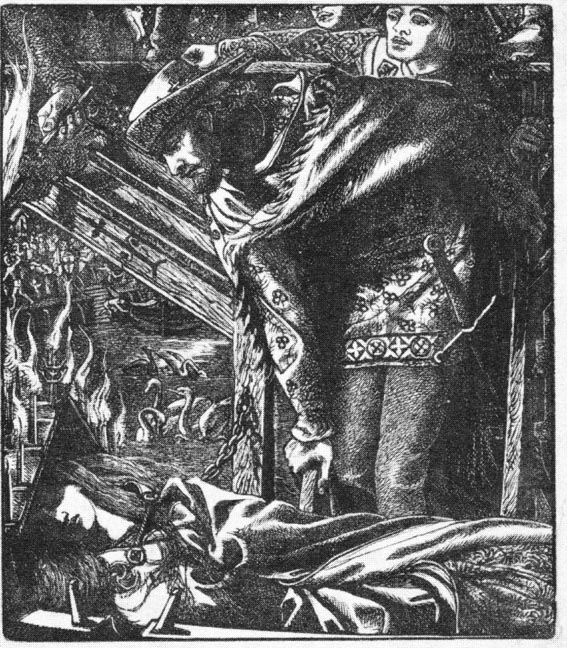

Often thought to have brought upon her own destruction; the victim of unrequited romance deserves no less support and validation for the injustice of her situation. The medieval roots of unrequited love lie in Tennyson's Lady of Shalott. As an artistic soul that longs to have a relationship with another individual, the embowered Lady lives in alone on an island, weaving "�by night and day / A magic web with colours gay." With only a mirror to see the life outside going by, she falls in love with Lancelot and pines away for him. Eventually destroyed by it, she resigns herself to death as she floats down to Camelot. The only artist to show the Lady's arrival at Camelot, D. G. Rossetti depicts Lancelot looking down at the dead Lady of Shalott in his illustration for the Moxon Tennyson. The subject of the wood engraving, the last quatrain of Tennyson's poem, emphasizes her paradoxical unraveling -- the Lady has given up everything, even her life, for love, and when she finally meets her love, her life is over. The chain that now ties the boat to its final moorings seems to become one with the clasps of the cloak around her neck, further sealing her fate (Nelson, "Pictorial Interpretations," Victorian Web). While it remains difficult to place blame on the unknowing Lancelot, Rossetti nevertheless alludes to his part in the Lady's death by including his presence in the design.

Often thought to have brought upon her own destruction; the victim of unrequited romance deserves no less support and validation for the injustice of her situation. The medieval roots of unrequited love lie in Tennyson's Lady of Shalott. As an artistic soul that longs to have a relationship with another individual, the embowered Lady lives in alone on an island, weaving "�by night and day / A magic web with colours gay." With only a mirror to see the life outside going by, she falls in love with Lancelot and pines away for him. Eventually destroyed by it, she resigns herself to death as she floats down to Camelot. The only artist to show the Lady's arrival at Camelot, D. G. Rossetti depicts Lancelot looking down at the dead Lady of Shalott in his illustration for the Moxon Tennyson. The subject of the wood engraving, the last quatrain of Tennyson's poem, emphasizes her paradoxical unraveling -- the Lady has given up everything, even her life, for love, and when she finally meets her love, her life is over. The chain that now ties the boat to its final moorings seems to become one with the clasps of the cloak around her neck, further sealing her fate (Nelson, "Pictorial Interpretations," Victorian Web). While it remains difficult to place blame on the unknowing Lancelot, Rossetti nevertheless alludes to his part in the Lady's death by including his presence in the design.

In "Light Love" (1856), fellow poet Christina Rossetti draws significant attention to the man's role in the seduction and betrayal of the female protagonist. As in many of her other poems, the woman's unhappiness is caused by the action of men who are often predatory, lazy, or lost in their own sensuality -- while the women often bear the consequences (D'Amico 98). The speaker's initial words reveal the love she still has for him, despite his betrayal. He callously suggests that the she find some other love, "left from the days of old," to provide for her. Only then does she recognize the emptiness of his love, contrasting it with the more enduring qualities of the maternal love she has for their illegitimate child. He compares the speaker with his blooming bride, the "peach" who "trembles within his reach" and "�reddens, my delight; / She ripens, reddens in my sight." When the speaker predicts that a similar betrayal might await his bride, he replies, "Like thee? nay not like thee: / She leans, but from a guarded tree." He implies that his bride-to-be woos him without giving away her chastity, thus contrasting the two women (D'Amico 97). However, he undermines his own comparison by using sensuous language to describe his bride: comparing her to a ripening peach whose inaccessibility ironically increases her worth and sexual appeal in his eyes (D'Amico 97). Rossetti also utilizes natural images of planting and harvesting and images of ripeness and unripeness to emphasize the ethereal nature of his seduction. Effectively abandoning his child's mother in search of a "ripe-blooming" carnal ideal, the man easily forgets his role in her destruction (D'Amico 99). "Thou leavest, love, true love behind" cries Rossetti's victimized woman, in a poetic dialogue not only with her false lover, but with the entire corrupt society he represents. His example exposes the hypocrisy of Victorian society and by the end of poem we see that the title applies to the man rather than the female -- it is for him that the nature of their love is "light" or of small importance (Harrison).

although not a member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, William Lindsay Windus created a painting entitled Too Late (1858) that captures another lovesick woman who literally wastes away due to her unmet desires. A quotation from the Tennyson poem, "Come Not, When I am Dead," accompanies it: "If it were thine error or thy crime/ I care no longer, being all unblest;/ Wed whom thou wilt; but I am sick of time,/ And I desire to rest" (lines 4-8). While the reason for her separation from her beloved remains ambiguous, her ruined health and broken heart are on full display for her belated lover's return. She appears sickly and frail, with sunken eyes and hollow cheeks. As a literally lovesick woman, she stands before her beloved, leaning on a crutch for support. Her haunting expression cements the pain he has caused while he turns his face away from her in agitation, pity and perhaps disgrace. although heavily criticized by Ruskin, Windus's painting clearly illustrates the extent to which the man can affect the telling of unrequited love.

The various depictions of the woman destroyed by love, in all its forms, often conclude with her final fate -- death. This forces us to question the permanent nature of her destruction: Does her death warrant justification? How might she have been saved? Many Victorians felt that death represented an inevitable and welcome release for the lovesick or fallen woman; particularly in the case of the adulteress and prostitute.

Having suffered from unrequited love, women such as Tennyson's wistful Lady of Shalott and frustrated Mariana and Windus's sickly invalid succumb to death by physical deterioration, as a manifestation of their mental state. No longer able to endure their desire for emotional and physical fulfillment, these women meet death as weakened shells of their former selves. Similarly, in "The Woodsman's Daughter," Coventry Patmore's tragic Maud goes mad and eventually drowns her illegitimate son. Seduced by the wealthy squire's son, the poor woodsman's daughter's ideal love cannot be realized due to their social class differences. Thus, although she remains alive, Patmore describes her fate as akin to death in the poem's last stanza: "The night blackens the pool, but Maud/ Is constant at her post,/ Sunk in a dread, unnatural sleep."

As an extension of this mode of destruction, suicide was viewed as the inevitable course of action for the adulteress and prostitute. Already outcast from Victorian society, these women were ultimately reduced to "the most abject poverty and wretchedness�their fate could only be premature old age and early Death" (Walkowitz, 39). This statement supports the common view that once a woman or girl had fallen, she was essentially unsalvageable. "The Bridge of Sighs" by Thomas Hood, describes the circumstances of the stereotypical solitary harlot and her brutalized existence:

The bleak wind of March

Made her tremble and shiver;

But not the dark arch,

Or the black flowing river:

Mad from life's history,

Glad to death's mystery,

Swift to be hurl'd --

Anywhere, anywhere

Out of the world! [lines 63-71]

Hood captures the instant before the woman commits suicide by jumping off the bridge, owing her weakness to "her evil behavior." Similarly, George Frederic Watts's Found Drowned, painted in 1848, depicts a suicide washed up under the arch of Waterloo Bridge. Both works assume we understand that the woman's fate before was worse than death, and therefore death would provide a welcome respite. Egg sets the last painting in his Past and Present series under the Adelphi arches of the same bridge, alluding to the woman's inevitable watery suicide out of guilt and remorse. In the same vein of Hogarth's moralizing engravings, such as Industry and Idleness, Egg uses his triptych to display adultery's most dire consequences. Not quite as didactic, the depiction of the woman's redemption at the hands of her wronged husband made fewer appearances. Egg's painting, as well as the works of Hood and Watts, demonstrate the lack of sympathy for the woman who destroys her own family and happiness; and to many Victorian audiences her death sentence seemed a fitting and gracious escape.

In contrast, the issue of how the fallen woman could be rescued or raised up again emerges in several Pre-Raphaelite works that present the possibility of spiritual redemption. In Morris's poem "King Arthur's Tomb," Guenevere finally chooses a life devoted to Christ instead of returning to Lancelot. although she struggles endlessly with her decision, she professes:

Yet am I very sorry for my sin;

Moreover, Christ, I cannot bear that hell,

I am most fain to love you, and to win

A place in heaven some time: I cannot tell:

Speak to me, Christ! I kiss, kiss, kiss your feet. [lines 177-180]

Such depictions of the fallen woman construct her as a remorseful victim and an object of sympathy rather than condemnation, allowing for the possibility of religious salvation. Most prominently featured in Hunt's The Awakening Conscience. The artist captures his subject at the sudden moment when she realizes the reprehensibility of her actions and recognizes her powerful desire to end them. Hunt alludes to this desire with his use of symbolism, most evident in the objects included in the gaudy domestic space. On the theme of her salvation, the song on the piano, "Oft in the Stilly Night," and the music scattered on the ground, "Tears Idle Tears," both reflect on a woman's childhood innocence. In the wallpaper, a vineyard, in which corn is mingled with the vine, falls prey to birds while the guardian boy sleeps, neglecting his duty. With obvious references to an earlier painting, The Hireling Shepherd, Hunt reveals that, like the grapes on the vine, a woman's chastity must not be left unguarded (Landow, Victorian Web). The cat and the bird on the floor parallel the positions of the man and woman, with both the bird and the woman seeking escape. And the soiled white glove on the floor foreshadows the woman's reputation, should she remain with her seducer. Utilizing typological and symbolic detail, Hunt chooses to focus on the hope for redemption and positions religion as the woman's savior from her sinful life. Christina Rossetti's fallen women poems, including "Light Love," often present religious redemption as the key to the woman's release. In "Light Love" the woman's lover abandons her, oblivious to her pleas, and in the end: "She raised her eyes, not wet / But hard, to Heaven / And asked / 'Does God forget?'" (Poems 1:138). This stanza reassures us that while the guilty man may go unpunished on earth, he will eventually be judged in Heaven. Both Hunt and Rossetti draw upon the Christian concept of a merciful and compassionate Christ, stemming from his acceptance of Mary Magdalene, who forgives all and warns none of us to cast the first stone. By allowing for the fallen woman to be raised up again, they appeal for the audience's sympathy over condemnation and encourage us to look upon those whom we might encounter in real life with the same compassion (Landow, Victorian Web).

In their depictions of the destructive nature of love, whether unrequited, tragic, illicit or forbidden, the Pre-Raphaelites often aimed for a degree of realism. However, they ultimately reinterpreted the actions and sensations of the real world and merged them with their own sympathetic ideals. Following Pre-Raphaelite tradition, many of the artists and writers emphasized the role of female sexuality, desire and the element of sensual passion in the woman's mental and physical destruction. Strong and healthy sex drives, once attributed to women in the Middle Ages, became a mortal sin during the Victorian age (Landow). Constantly looking at the medieval era for inspiration, it seems appropriate that many Pre-Raphaelites sought to restore this medieval belief and make sexuality less taboo in Victorian society. although the Pre-Raphaelites' attempts to blend fine art with social history did not always meet success, their consciousness of social imbalances allowed them to reveal and challenge various depictions of love; constantly remaining faithful to their belief that: "There is love, and sometimes delight, but never untempered happiness" (Hilton 209).

Works Cited

D'Amico, Diane. Christina Rossetti: Faith, Gender, and Time. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1999.

"Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 16 October 2003-18 January 2004." National Museums Liverpool. December 2004.

Edelstein, T.J. "Augustus Egg's Triptych: A Narrative of Victorian Adultery." 125 (April 1983) Burlington Magazine.

Harrison, Anthony H. "Love and Betrayal," Christina Rossetti in Context. Victorian Web. Ed. George Landow. 1993. December 2004.

Hilton, Timothy. The Pre-Raphaelites. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1970.

Landow, George. Replete with Meaning: William Holman Hunt and Typological Symbolism. Victorian Web. 8 December 2004.

Nelson, Elizabeth. "Pictorial Interpretations of 'The Lady of Shalott': The Lady in her Boat." Victorian Web. 8 December 2004.

Nelson, Elizabeth. "The Embowered Woman: Pictorial Interpretations of 'The Lady of Shalott.'" Victorian Web. 8 December 2004.

Nochlin, Linda. "Lost and Found: Once More the Fallen Woman." Art Bulletin, 60. 1978.

Walkowitz, Judith. Prostitution and Victorian Society. Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Wood, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Seven Dials, Cassell, 1981.

Last modified 19 December 2004