The author has very kindly allowed us to reprint this review, which originally appeared in The Library, 6/3 (September 2005): 354–356. Links and illustrations have been added. Click on the illustrations to enlarge them. — Jacqueline Banerjee

In 1890 the twenty-seven-year-old Lucien Pissarro went to London to research William Morris's social model of the integration of art and life through the role of the artist-craftsman. There Lucien (he is "Lucien" to differentiate him from his more famous father, Camille Pissarro) met two people — Charles Ricketts and Esther Bensusan — who, Marcella D. Genz argues in her History of the Eragny Press 1894-1914, would be pivotal to the path his life was about to take. Thanks to Ricketts, Lucien gained a new understanding of the craft of wood engraving and its relationship with the art of the book. Because of Bensusan, whom he married, Lucien chose to settle in England rather than France. The result of these two associations was the Eragny Press, whose productions were unique, beguiling hybrids of French art and English design.

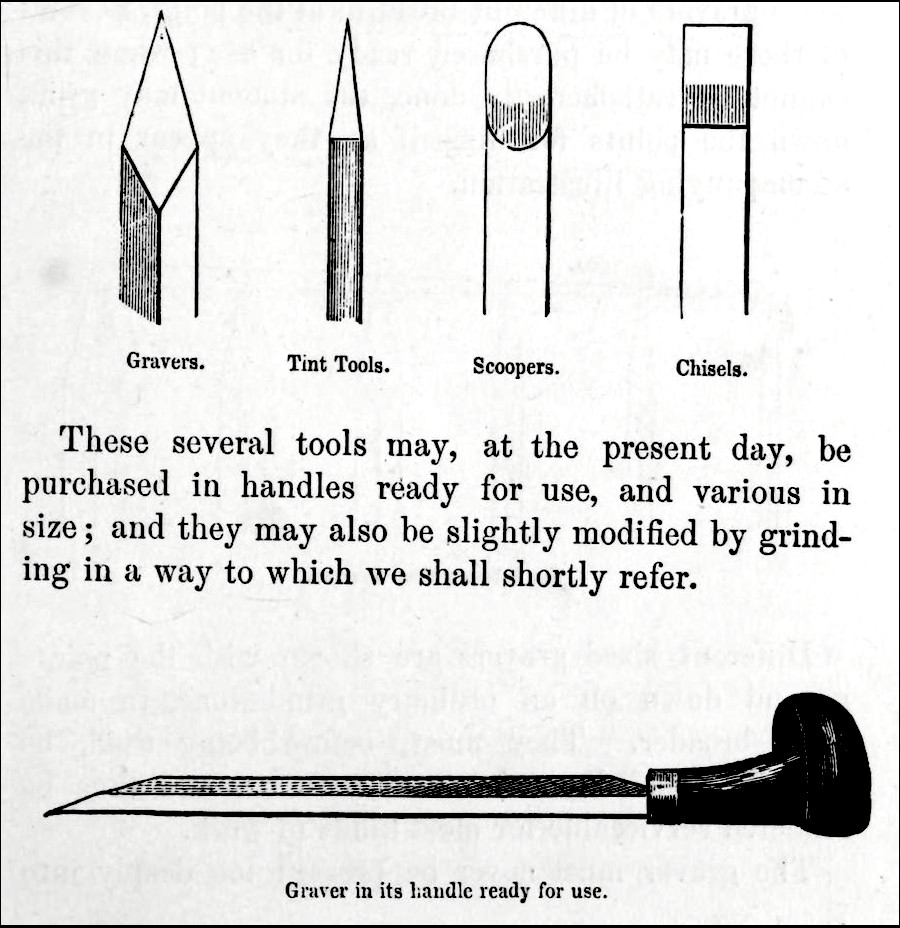

The History of the Eragny Press is clearly the result of years of research. Marcella Genz's grasp of the economics of book production and sales is formidable, and the information contained in her chapters on these topics is useful and interesting. Her knowledge of the history and nature of wood engraving, however, appears to be more limited. Genz writes that "each line of the drawing made by the engraving tool is the same sort of line as that for each letter made by the tool of the punch cutter" (131). What she is presumably trying to say is that because the wood engraver's burin digs a single furrow into an end-grain block, only one stroke is required to produce the characteristic white line of wood engraving, which is a relief printing process, like type.

Carvers (the older name for

burins) in Giles 15.

Wood engraving (a subcategory of the woodcut, capable of finer detail) is carved into end-grain blocks with a burin rather than a knife. Genz believes that the integration of wood engravings with type "was a rather startling notion to the more traditional French bibliophiles" (84). But the handmade quality and type-compatibility of woodblock printing were the reasons bibliophiles of the period considered it the most appropriate medium for book illustration.

The problem for publishers of artist books was that, except for painter-craftsmen like Auguste Lepère, who at Camille's behest gave Lucien his first lesson in wood engraving in 1885, or renegade geniuses like Paul Gauguin, who ignored craft conventions, it was the rare painter who had the patience to learn wood engraving. (Millet tried it; Lucien's father never did.) Lucien's learning curve was a steep one, but after a few years and some additional lessons from Ricketts on how to draw for the woodblock, Lucien got to be quite good at it. Genz is mistaken, however, when she asserts that Lucien was "single-handedly promoting the revival of original print media, especially wood engraving" in France (27). Lucien was one of many, in France as well as in England.

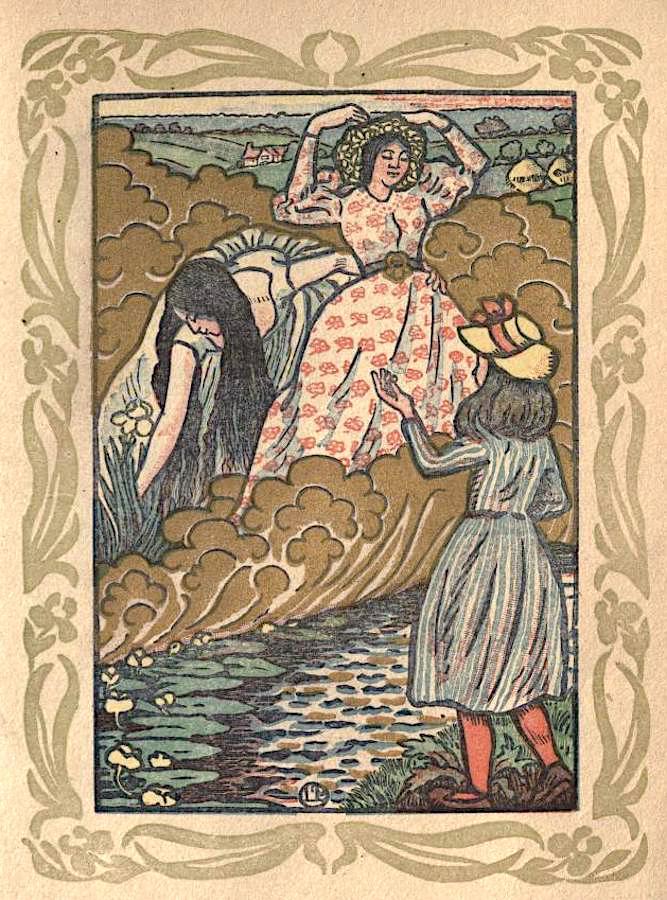

Genz characterizes Lucien's work as Impressionist, asserting that his colour wood engravings explore "Impressionist sensation" (12). But Lucien was of the same generation as the Nabis—Bonnard, Vuillard, et al. He shared with them an interest in absolute reality within everyday reality — thus his use of gold in the printing of his first book, The Queen of the Fishes (1895), and in his later books. This tendency toward Symbolism was a source of tension with Camille, a positivist who couldn't stand the Symbolists. Despite his father's constant coaching, Lucien's decorative line and subtle, evocative use of pattern and colour has more in common with the Nabis than with the Impressionists.

The last and only full page colour

illustration in Queen of the Fishes.

Genz points out (several times) that Ambroise Vollard, in his Recollections of a Picture Dealer, credited Lucien's lovely and technically accomplished Queen of the Fishes with spurring him to begin publishing books illustrated by painters. We know from the Pissarro letters that in 1896 Vollard spoke to Camille about having Lucien work on an illustrated edition of Verlaine. Genz suggests that the collaboration never came to pass because by the time Vollard felt he could afford to publish Parallèlement (1900), Lucien "was established in London and was no longer seeking work in France" (88). But by 1897 Pierre Bonnard was already working on illustrations for Parallèlement, so Vollard cannot have been very serious about Lucien when he spoke with Camille the previous year. Lucien suspected as much: "ce n'est pas que je presse un instant Vollard au sérieux," he wrote his father after asking why he had heard nothing more about the project.

In the end, Vollard's large, stunning Parallèlement was about as different from Lucien's charming little Eragny Press productions as can be imagined. Despite his sagacity in the business of selling art, however, Vollard would not have much more success than Lucien in marketing his artist books.

Some final quibbles: although handmade paper does vary somewhat, the measurements in Genz's "Descriptive Bibliography" are not always accurate. Her reproductions are limited, both in number and by the fact that, except for its dust jacket, the book contains no colour. (The economics of book publishing apparently still exerts its malevolent influence.) This is disappointing in that, as Genz quite rightly emphasizes, colour is the most distinctive quality of Eragny Press books. Likewise disappointing in a publication devoted to a pair of book perfectionists (Lucien and Esther were a true team, as Genz makes clear) are the occasional typographical errors: a stray period here, a mysterious space there.

In the end, though, Genz gets it right in stressing that the Eragny Press was the only private press of the period to attempt the difficult process of colour printing from multiple blocks. It was this, she writes, along with the autograph, personal nature of its productions, that made the Eragny Press the only art press "wholly of its time" (12). This important case Marcella Genz makes very well indeed.

Bibliography

[Book under review] Genz, Marcella. A History of the Eragny Press, 1894-1914. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press and London: The British Library, 2004. 240 pp. $85. ISBN 1-5846-107-6 (USA) 0-7123-4862-X (UK)

Illustration Sources

Giles, Thomas. The Art of Wood Engraving: A Practical Handbook. London: Windsor and Newton, 1875. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Getty Research Institute. Web. 9 April 2021.

Rust, Margaret. The Queen of the Fishes, An Adaptation in English of a Fairy Tale of Valois. London: Ch. Ricketts, 1894 (by the Eragny Press). Internet Archive. Contributed by University of California Libraries. Web. 9 April 2021.

Created 9 April 2021