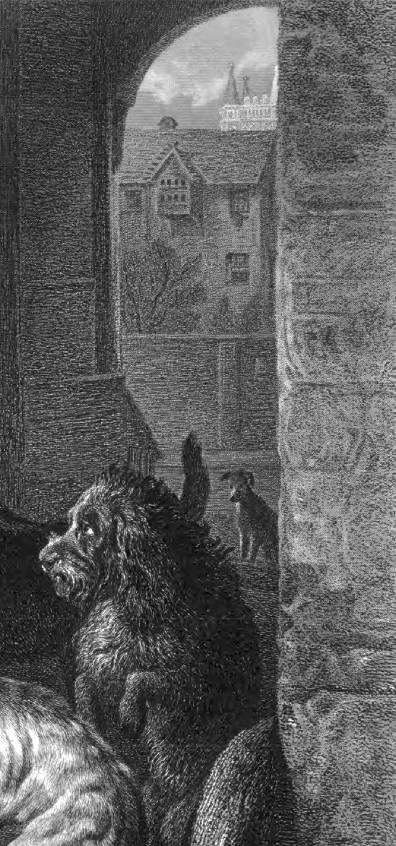

Jack in Office by Sir Edwin Landseer, R.A. C. G. Lewis, Engraver. 1833. Source: Art-Journal. [Click on image to enlarge it.] Formatting and text by George P. Landow [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Internet Archive and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Details. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Commentary by The Art-Journal

This is one of Sir Edwin’s comparatively early works; it was painted in 1833; but we may challenge the entire catalogue of his subsequent pictures to show anything more characteristic of dogology than this most humorous and eloquent composition; for every animal is speaking in his own appropriate language, as nature, in accordance with his necessities or demands, prompts. First of all, there is the “man in possession,” a strong-built, ill-tempered mastiff, whose personal appearance evidences that he never knows the want of a meal, though his master possibly feeds him well to get plenty of work out of him; as an Italian writer on political economy, some quarter of a century ago, says we English are always accustomed to do with regard to our servants for a similar reason. The owner of the dog has left him in charge of the meat-barrow while he delivers some “goods;” or, perhaps, has betaken himself to a public-house close at hand for refreshment. The animal appears quite equal to his duty, and quite as ready to perform it. He sits and watches the group around him with supreme indifference to their wants, and with manifest determination to repel any attack which might be made on the savoury viands. The selfish and pampered creature is but a type of a certain class of human beings, who care little or nothing, for others so long as they prosper and have their desires satisfied. Landseer has painted a moral in this representative dog. The vendor of dogs’ and cats’ meat is almost invariably accompanied on his round by a train of followers enticed by the luxuries he has for sale. Here is a group diverse in character as in kind. Foremost is a wretched, half-starved hound, a fitting candidate for the “home of the homeless.” It is clear she has an owner, for the broken cord round her neck tells she has stolen away from her master: and no wonder when we look at her condition. She eyes the tempting bit in the plate, and would fain make an attack on it, but fear and weakness restrain her. Behind is a kind of French poodle; he does not appear to be an object of commiseration, and yet his appeal is . . .; as if any argument short of brute force could move to pity any “ Jack in office,” much less such an overfed specimen as that enthroned on the barrow. There is, however, one at a little distance from the others whose erect head and tail indicate that he is rather disposed to try conclusions with him: he is a surly fellow, whose incipient growl has perhaps caught the ear of the meat-seller’s locum teams, and is recognised as a sort of battle-cry. In the front of the barrow is a perky little mongrel who has succeeded in filching a skewer, probably flavoured with meat, and crunches it with the most bare- faced impertinence before the face of the canine Dogberry. At the entrance of the gateway, in the far distance, is yet another animal, too timid, probably, to approach nearer to a possible scene of conflict, but ready to take his share of the prey when it may be done with safety, discretion being with him “the better part of valour.” This picture, it is almost needless to say, is admirably painted throughout.

Bibliography

“Selected Pictures from the Sheepshanks Collection. Jack in Office.” Art-Journal. Internet Archive. Web.

Last modified 10 November 2014