A Jew's Daughter Accused of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages [A Desperate Plea], by John Evan Hodgson (1831-1895). 1866. Oil on canvas. 34 ¼ x 48 ¼ inches (87 x 122.5 cm). Private collection. Image courtesy of Bonhams. [Click on this and the following image to enlarge them.]

Hodgson exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1866, no. 574. It sold recently at Bonhams in 2010 under the title A Desperate Plea. The painting shows a young Jewess pleading her innocence against an accusation of witchcraft raised by a couple who charge that it is at her instigation their young son has fallen ill. Antisemitism was rife throughout Europe in the Middle Ages. In much of the continent Jews were denied citizenship and its rights and were barred from holding posts in governments and the military. Jews were also excluded from memberships in guilds and the professions. The segregation of the Jewish populations of towns and cities into ghettos first dates from the Middle Ages. The success of some Jews in trade, banking, and moneylending aroused the envy of certain segments of the population. This economic resentment, combined with religious prejudice, led to the forced expulsion of Jews from several countries at various times during the Middle Ages. In England, for instance, this occurred in 1290 under King Edward I, while in Spain its long-established Jewish population was expelled in 1492 under the reign of under King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella unless Jews converted to Christianity. (Britannica). Witchcraft was heavily associated with women, particularly those in the Jewish culture, during the Middle Ages. The idea for Hodgson's painting may have originated from Sir Walter Scott's famous novel Ivanhoe, first published in 1819, where the Jewess Rebecca is accused of witchcraft, likely because in addition to being a woman and a Jew she was also a medical healer.

When the picture was shown at the Royal Academy it was extensively reviewed. The critic of The Art Journal found this the finest work Hodgson had exhibited to this point: "Mr. Hodgson has chosen a subject cognate with the one painted by Mr. Pettie. The Jew's Daughter accused of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages (574), is the best work Mr. Hodgkin [sic] has yet exhibited. The accused girl may be over spasmodic, and there is still something wooden in the figures generally. But yet we gladly acknowledge that the artist has advanced considerably even within the last year (164).

John Pettie had exhibited The Arrest for Witchcraft, no. 179, at that same exhibition.

F. G. Stephens in The Athenaeum found the work a great improvement in Hodgson's skill in executive qualities but not in its design: "Mr. J. E. Hodgson's Jew's Daughter accused of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages (574) shows a remarkable change in the style of the artist who produced that very striking landscape-history picture, The Arrival of the Spanish Armada, here a few years since, and a great improvement on the executive qualities of more recent works. A Jewish lady has come to the feet of a peeress or queen, who is seated on a throne, and receives with evident sympathy the appeal for safety for the persecuted. Attendants stand before this group; the incident is well told, being expressed with perfect clearness in the design: that design is not so grave and thoughtful an order as was before chosen by Mr. Hodgson; the ability it displays is inferior to that which dealt, in so great a spirit, with the Armada on the southern coast of England. In short, here is more skill, but less thought that was worth painting than before" (639).

A reviewer for The Builder found it clever in execution but not much originality in its conception:

A Jew's Daughter accused of Witchcraft, by Mr. J. E. Hodgson, has its subject made apparent, though the Middle Ages are the epoch assigned to it; but it is the more easily comprehended from some dramatic expressiveness, and more particularly from the introduction of evidence to sustain the accusation – in an attenuated child for whose decline the supposed sorceress is protesting she is not answerable. There is not much originality either in the conception or treatment of this work; and although remarkable with many others, by others, for clever executive ability, it is less attractive than in former applications of its use by the same painter. [361]

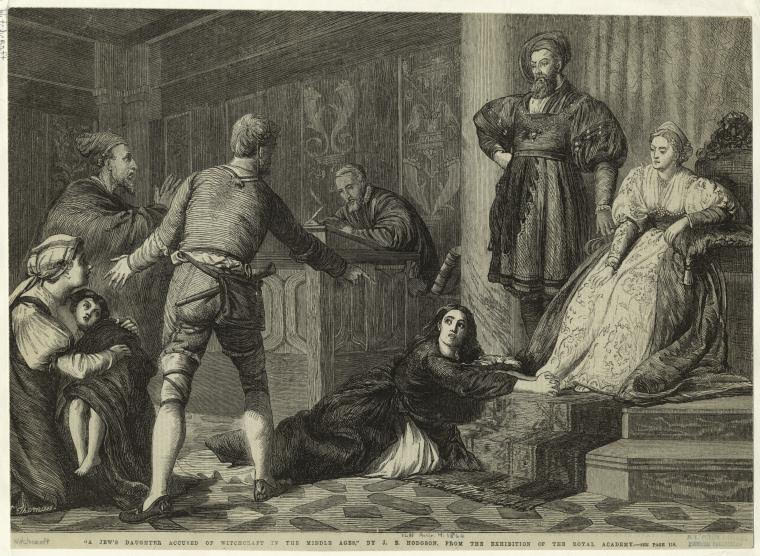

A Jew's Daughter Accused of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. Wood engraving by William Thomas after J.E. Hodgson from The Illustrated London News, August 4, 1866. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library, image ID: 834533.

The Illustrated London News initially called Hodgson's picture, "of prominent importance, which we regret we have no room to review this week" (474). Despite this initial short shrift, later in the year the periodical chose to reproduce a wood engraving of it by William Thomas in the 4 August 1866 issue (p.109). The picture was also extensively reviewed at that time where the critic found it a marked technical advance on Hodgson's previous work:

A Jew's Daughter Accused of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages. To clothe, as it were, with flesh and blood, and to revivify the dry bones of the past has always been justly regarded one of the noblest prerogatives of art. The Past: the more thoroughly we can realize it, the more pregnant with teaching will it be found for the Present. In the picture we engrave, and which will be remembered by visitors to the Royal Academy exhibition just closed, the artist has not only reproduced the outward aspect of a most picturesque phase of bygone life – that is, the superb costumes, and the richly-decorated stately hall or court of an Italian prince of the 15th century – but he has imagined an episode full of intense and varied passion and feeling. More than this, there is a moral intention in his choice of incident, not merely of individual application, but of wide relation to the human family in all circumstances of ignorance. He shows us a consequence of blind superstition and national prejudice at a period when (though glorious in some respects), men's minds were still enslaved and besotted by the unreasoning, priestly, spiritual terrorism of those rightly-named "dark ages," which owe their darkest shades to the foul stains of crime. The most superficial readers of history will not require to be reminded of the frightful atrocities perpetuated down almost to our own time through the insane belief in witchcraft and the power of the Evil One. And it is equally unnecessary to recall the unjust extortions and horribly cruel persecutions to which the poor Jew was subjected in every country of Christendom. Did a child in the course of nature – or, if you will, by visitation of Providence – fall sick, and where the doctor and the priest called in, what more probable than, finding the mysterious malady succumb neither to the empiricism of the one or the prayers of the other, and the belief in witchcraft being universal, that both should direct suspicion to some poor, friendless woman, of strange and lonely habits; or, better still, to some miserable, alien, unbelieving Jewess; an incident of the latter the painter places before us. Under the sway of ignorance and superstition, such vague presumptions of guilt quickly acquire the force of a full conviction – of absolute certainty. So the father comes before the tribunal, and, pointing to his sick child, in the imploring mother's arms, unhesitantly proclaims it to be bewitched by the Jewish sorceress, the despised and secret enemy of the Christian. Knowing full well the imminent peril of her situation, the Jewish maiden, in Oriental fashion, prostrates herself at the feet of her judge in an agony of supplication, while her father clasps his hands before his gabardine in a passionate appeal for mercy. It was, we think, finely imagined by the painter that the calmly judicial Prince has resigned the trial of such a case to his beautiful and noble wife. And in her sweet, womanly face we trace compassion struggling with superstition. Thus the artist, while leaving us in uncertainty, contrives to enforce his dark moral, and yet to illuminate it with that ray of pity, and hope which always relieves with advantage either a painted or written drama. In this picture Mr. Hodgson, in addition to its admirable conception, exhibited a marked technical advance, especially in solidity and richness with sobriety of colour; and we may add with perfect fairness that none of our young and promising painters of figure-subjects not yet recipients of Academic distinction have better claims to the honour. [118]

The critic of The Spectator praised certain aspects of the painting while deploring its colouration:

The pictures which provoked criticism are those where great ability of one kind is marred by shortcomings of another; and the remarks here hazarded are made with special reference to Mr. Hodgson's Jewess Accused of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages (574). The picture is marked by many excellent qualities indicative of a cultivated mind. The story is well told, without any grimace, and the hasty and interested conclusions of the accuser, to whom the undeniable fact of his child's sickness is as satisfactory proof of the poor Jewess's guilt as existence of certain bricks in his father's chimney was evidence to Shakespeare's clown of Mortimer's illegitimacy, is forcibly contrasted with the calmer attitude of the baron and his lady to whom appeal is made. But the colour is "leathery," and especially wanting in the refinement to be obtained by attention to atmospheric accidents of hue. [578]

Interestingly, Tom Taylor, in contrast, praised the colour of this work: "In his next year's picture Mr. Hodgson went further back, to the Middle Ages, for a painful, even tragic subject – a Jewess accused of witchcraft, and endeavouring to melt the heart of the châtelaine, before whose lord she is brought for trial. There was strong, though, as was to be expected from Mr. Hodgson, unexaggerated expression in the agonized and terror-stricken Jewish maiden and her miserable father; and the picture was richer and juicier in colour than anything yet exhibited by the painter" (18).

Bibliography

"Anti-Semitism in Medieval Europe." Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/anti-Semitism/Anti-Semitism-in-medieval-Europe

British and Continental Pictures. Bonhams, London, Knightsbridge (November 30, 2010): lot 259.

"Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Builder XXIV (May 19, 1866): 360-361.

"Fine Arts. Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Illustrated London News XLVIII (13 May 1866): 474.

"A Jew's Daughter Accused of Witchcraft in the Middle Ages." The Illustrated London News XLIX (4 August 1866): 109 &118.

Stephens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 2011 (12 May 1866): 638-40.

Taylor, Tom. "English Painters of the Present Day. XIX - J. E. Hodgson." The Portfolio II (1871): 17-19.

Created 17 January 2024