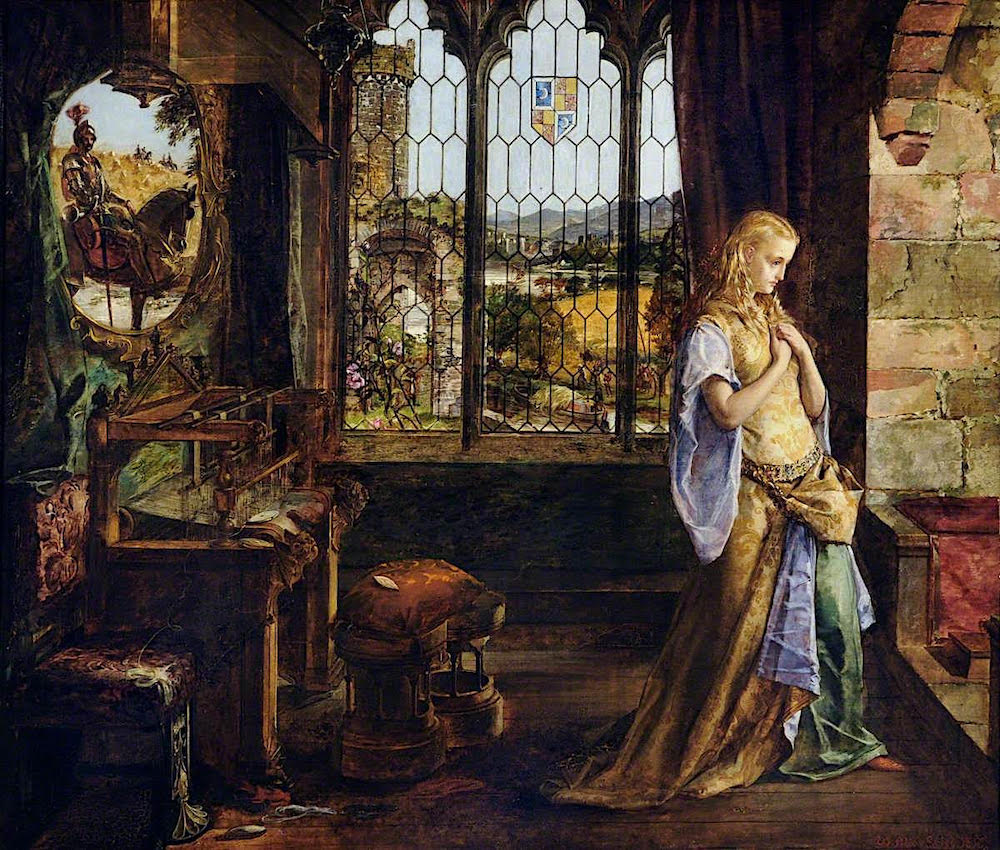

Lady of Shalott by William Maw Egley (1826–1916). Oil on canvas. 34 5/8 x 39 5/8 inches (88 x 100.7 cm). Collection of Sheffield Museums. Accession no. VIS.630. Image via Art UK on the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (CC BY-NC-ND).

Egley exhibited this painting at the British Institution in 1858, no. 373, accompanied in the catalogue by lines from Alfred Tennyson's poem "The Lady of Shalott." An old label on the verso of the frame contains these lines from the poem:

There she weaves by night and day

[...]

From the bank and from the river

He flash'd into the crystal mirror. [...]

She left the web, she left the loom.

She made three paces thro' the room,

She saw the water-lily bloom,

She saw the helmet and the plume

In its bright colouring and meticulous detail this painting can be seen as another example of Egley's being influenced by the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism while the choice of an Arthurian subject links it to the second phase. In his diary Egley provided a brief description of this work: "The figure in profile looking from a window on the right. On the left, the loom; and over it a mirror, in which is reflected a knight on horseback." According to his diary Egley spent thirty-nine and a half days working on the painting. This was obviously not the only work based on Tennyson that Egley was to portray. He had earlier painted The Talking Oak in 1857 and then later Margaret in 1860, and Fair Rosamund in 1871, both the latter heroines suggested by Tennyson's poem "A Dream of Fair Women."

Closer view of main figure.

The model for the pale and pensive maiden portrayed in The Lady of Shalott, with her hands clasped across her heart, was Egley's wife Mary Anne Hubbard. Her costume with its ruched gold gown and mauve sleeves, close fit hip-girdle, brightly coloured underskirt, and pointed red shoes was derived from fourteenth century sources (Banham and Harris 168). Barnham and Harris point out, however, that a tapestry would have been woven upright at this period and not as shown in Egley's painting.

Egley's picture shows the maiden has left her loom to gaze down from her window upon Lancelot riding below on his steed, despite the fact that she knows this action will bring the curse upon her. As Elizabeth Nelson has pointed out Egley's painting occurs before the most dramatic part of the story, the curse descending upon her leading to her doom:

Egley also defines the Lady by the luxury that surrounds her, in contrast to Tennyson's "four gray walls." Egley's Lady of Shalott presents the Lady in a richly appointed interior room. She has left the loom to look out at Lancelot, whose reflection appears in the mirror above her tapestry. Unlike Hunt's version of the Lady of Shalott, which illustrates the moment the curse descends upon the Lady and she realizes her fate, Egley concentrates upon the wistful yearning of a young maiden's love. The large window in the background provides a view of a romantic landscape and a river flowing into the unknown world, conveying the pensive mood and wistful longing of the lady while emphasizing the contrast between the Lady's interior tower and the colourful exterior world of romance. [10]

Certainly the rich interior of the Lady's room feels much less claustrophobic than the "four gray walls" described by Tennyson and provides much more temptation to view the outside world through her large mullioned leaded windows and therefore trigger the curse. The bright sunlit exterior world contrasts sharply with the gloom of her apartment in the castle. The view of the river outside her window and the barge in the midground prefigure that latter part of the tale that is frequently portrayed by Victorian artists of the dead body of the Lady floating down the river to Camelot, which can be seen in the distance.

Closer view of the "romantic landscape" in the "exterior world."

Wooten has pointed out the trouble Egley took to realize his vision for the picture:

The artist invested great deal of energy in realising his High Gothic version, modelling the architecture on Conway Castle and sketching in the field for the rural landscape in the background; for example, "the river/ Flowing down to Camelot" is based on drawings of the canal at Kensal Green, north-west London. However, such studied accuracy merely serves to enhance the overall mood of the painting. Meticulously rendered details, for example, the carved bats fashioned like gargoyles which adorn the loom, are not symbolic or suggestive of a deeper, subtextural intent but decorative. [133]

Wooten found Egley's picture somewhat difficult to categorise, coming between a conventional Victorian work and a progressive piece of Pre-Raphaelite painting:

The status of the picture cannot be adequately defined as conservative or radical; the work is finely balanced between the conventional and the subversive. The artist adopted the more accessible and aesthetically-pleasing aspects of Pre-Raphaelitism, whilst avoiding any serious commitment to the movement's precepts; he was also unable to invest his work with any visionary vigour. [136]

When this work was shown at the British Institution in 1858 critics noted its debt to Pre-Raphaelitism but a reviewer for The Athenaeum failed to be impressed: "Of flagrant Pre-Raphaelitism, Mr. W. Maw Egley gives us an ill-favoured specimen in his Lady of Shalott (214). A critic for The Saturday Review in turn commented: "The Lady of Shalott (373), by Mr. W. M. Egley, is a picture that will deservedly attract much attention. It is conscientiously wrought out, and shows resources and ambition in its author. He must beware of the worst dangers of Pre-Raffaelitism" (190).

The Lady of Shalott was a popular subject for Victorian and Edwardian painters. Christine Poulson has noted that between 1850-1915 there are at least sixty-eight works of art based on it, including versions by William Holman Hunt, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, John Everett Millais, Elizabeth Siddal, Arthur Hughes, Joseph Noel Paton, Walter Crane, John William Waterhouse, John Atkinson Grimshaw, and Sidney Meteyard (179). Egley was one of the first artists to paint a version of this subject following the publication of the Moxon Tennyson in 1857 with its wood engravings of this subject by Hunt and Rossetti. Jan Marsh therefore pointed it out "as relatively early example of the influence of Pre-Raphaelite medievalism on other artists" (150).

Links to Related Material

- Text of Tennyson's "The Lady of Shalott"

- Pictorial Representations of Tennyson's "The Lady of Shalott"

Bibliography

Banham, Joanna, and Jennifer Harris, eds. William Morris and the Middle Ages. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984.

Egley, William Maw. Diaries. Victorian and Albert Museum MSL/1940/480-487.

"Fine Arts. British Institution." The Athenaeum No. 1581 (13 February 1858): 213-14.

The Lady of Shallot. Art UK. Web. 17 July 2024.

Marsh, Jan. Pre-Raphaelite Women: Images of Femininity in Pre-Raphaelite Art. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1984.

"The Modern Masters at the British Institution." The Saturday Review V (20 February 1858): 189-190.

Nelson, Elizabeth. "Tennyson and the Ladies of Shalott." In Ladies of Shalott: A Victorian Masterpiece and its Context. Providence: Brown University, 1985. 4-16.

Poulson, Christine. The Quest for the Grail: Arthurian Legend in British Art, 1840-1920. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1999.

Wooten, Sarah. "William Maw Egley's 'The Lady of Shalott.'" Tennyson Research Bulletin VII, no. 3 (November 1999): 132-140. https://www.jstor.org/stable/45287831

Created 18 July 2024