Pegwell Bay, Kent — a Recollection of October 5th, 1858 by William Dyce. 1858-60. Oil on canvas. 25 x 35 inches (63.5 x 88.9 cm). Collection of Tate Britain, accession no. N01407. Image courtesy of Tate Britain, under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence (CC BY-NC). [Click on the images on this page to enlarge them.]

Dyce exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1860, no. 141. It is his best-known landscape, and a masterpiece of Pre-Raphaelite landscape art. Its importance even at the time is shown by the fact that it was later exhibited at the International Exhibition held at South Kensington in London in 1862 and the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1867.

Pegwell Bay is located on the Kent coast, just south of Ramsgate and north of Sandwich, where the river Stour flows through Canterbury to reach the English Channel. Dyce may have begun the painting in the autumn of 1858 when he was in the Ramsgate area spending six weeks on holiday with his family, but it was primarily worked up later from memory aided by a pencil sketch and a watercolour study, now in the collection of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museum. The watercolour has variously been dated to October 1857 or 1858 because the inscription is difficult to decipher and the family may have vacationed at Ramsgate the year previously. In the finished painting the time portrayed is a cool autumn day with the tide out and the luminescent evening sky reflected in the sea.

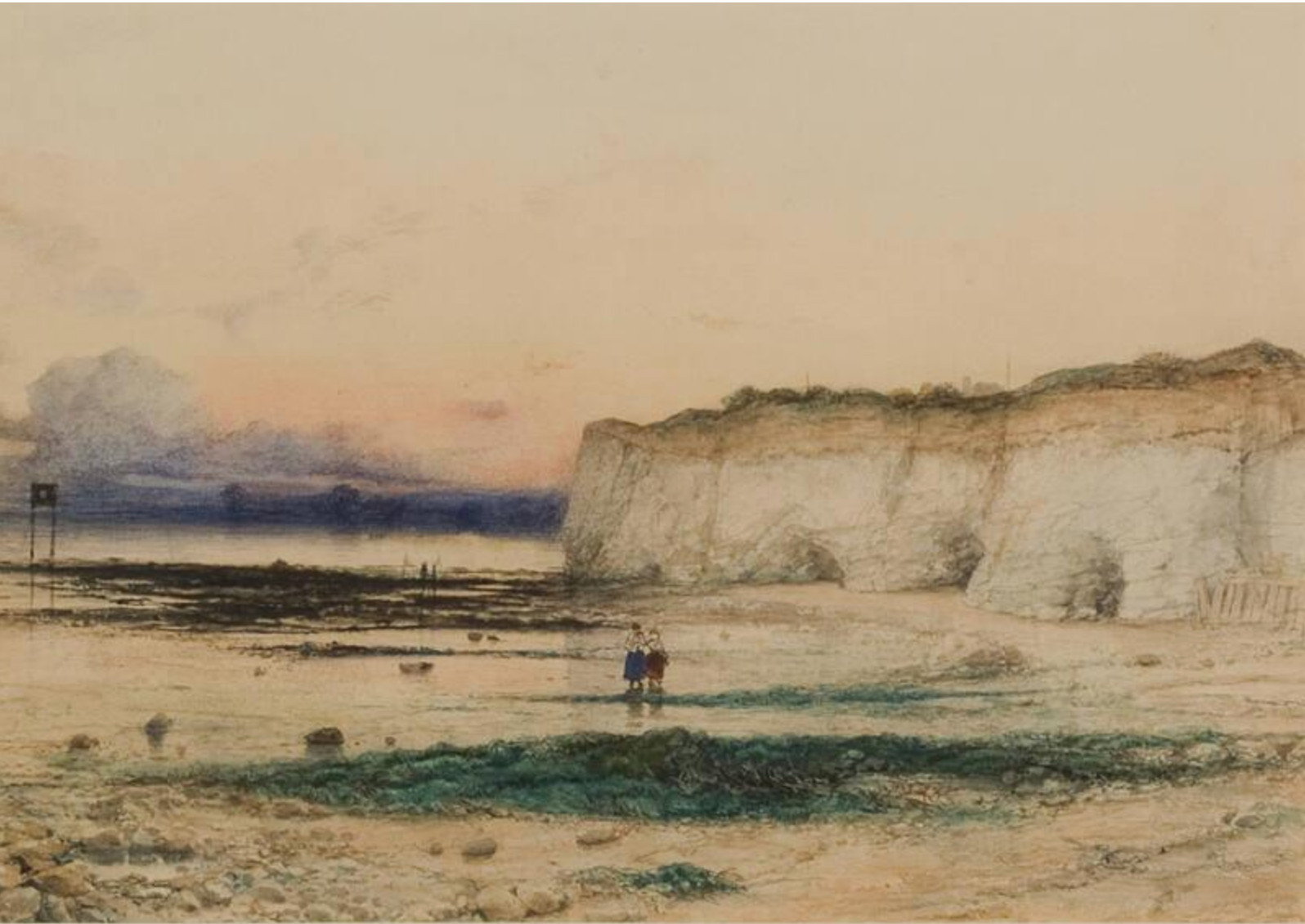

Study for Pegwell Bay, Kent, c.1857-58 Watercolour on paper: 9 5/8 x 13 1/2 inches (24.4 x 34.4 cm). Collection of the Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums. Image identified as being in the public domain.

Jason Rosenfeld considers the view shown in Pegwell Bay to be essentially west-southwest, showing an unexpected view of sunset on the east coast, and putting the time at early evening around half past five (110). Allen Staley feels this picture lacked the "sunny pleasantness" found in much of Pre-Raphaelitism and instead felt "the landscape is bleak, the figures collect their shells with a seriousness that verges on gloom, and the mood is distinctly melancholy" (168). In the foreground can be seen members of Dyce's family, painted, in Rosenfeld's opinion, with "the delicacy of miniature portraits" and "huddled with scarves and layers to ward off the autumnal evening chill" (110). From right to left are his wife Jane, her sisters Grace and Isabella Brand who are picking up sea-shells, and one of his sons, presumably William who would have been six in 1858, seen holding a shovel. Christiana Payne points out that the women are wearing "good quality, warm, sensible clothing rather than fashionable dress…. Although the different colours and stripes suggest that Dyce's wife and sisters-in-law have put together their apparel with good taste and flair, they are different from the women depicted in other Victorian paintings of seaside scenes … women in the 1850s used a day at the seaside as an opportunity to display their best silks and satins, accompanied by pretty bonnets, wide-brimmed straw hats, lacy shawls and parasols." Dyce himself is likely the man carrying artist's materials under his right arm seen in the midground to the far right. In the background are additional figures and three donkeys with their attendants.

Dyce and Photography

When the finished painting was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1860 some contemporary critics felt the view was based on a photograph. James Dafforne in The Art Journal in 1860 refuted that belief: "The picture of Pegwell Bay was spoken of by many critical writers as having been painted from a photograph; and its wonderful elaborate detail favoured the supposition; but we happen to know it was done from memory, aided by a slight and hasty sketch, in pencil, of the locality" (296). Marcia Pointon has also concluded that Dyce's painting was not based on looking at a photograph of this view:

William's vision and his way at looking at landscape was probably modified not by looking at photographs but by his knowledge of how landscape appeared through a camera lens…. In so far as the rendering of the landscape in Pegwell Bay presents an air of exactitude, it is the result of artistic manipulation and the feeling of photographic realism in the painting is an illusion, albeit an assiduously cultivated illusion. The realism of Pegwell Bay is not an end in itself, but a vehicle for the expression of an intellectual response to a scene which is also imbued with strong personal feeling. Pegwell Bay is a painting about time, explored through an image of a particular moment in time. [171]

The particular moment, of course, is the appearance of Donati's comet at its most brilliant in the evening sky.

This was, in several respects, an unusual portrayal of a family on holiday. As Alison Smith says, "In contrast to the ebullient mood of most seaside depictions, Dyce's image is solemn and melancholy, a quality enhanced by the isolated, strung-out figures shown in solitary communion with nature – a topos more typical of photography than painting although it was unlikely Dyce used photographs as an aid, despite his interest in the medium" (188). Staley was also convinced that, rather than using photography as a study, Dyce may have adopted "stylistic suggestions" from photographs by his friend David Octavius Hill and others. He also pointed out that if Pegwell Bay was compared to a contemporary photograph of the same locality, Dyce "not only equalled but outdid the camera in clarity and thoroughness" (167). Dyce's use of pale, muted colours and what Tim Barringer refers to as "a certain flattening of the image" was certainly reminiscent of the newly developed photographic technology, however (81). Rosenfeld therefore feels it is possible that Dyce's picture was based on a photograph, now unlocated, because it bears a generally monochromatic tonality related to photography (110). Barringer sums up this controversy by stating: "While these allusions to photography underscore the painting's modernity, its evocation of mood and its underlying philosophical grandeur single it out as one of the supreme imaginative achievements of Victorian art" (81).

The Painting's Reflection of Dyce's Scientific Interests in Astronomy and Geology

Malcolm Warner felt the work

hardly expressed the domestic togetherness normally associated with the "conversation piece." Impassive and isolated from each other, the figures seem engaged in some activity far more solemn and significant than what they are actually doing, which is collecting sea-shells. Their scale establishes them as fairly distant from the spectator, yet they are seen in crisp focus, which slightly detaches them from the setting and helps create an overall mood of unease. This is enhanced by the way Dyce's wife and son look enigmatically off to the left at something the spectator cannot see. Stranger still is what they are not looking at – for in the sky above them, apparently noticed only by the artist, is a comet. [182]

Beachcombing and collecting sea-shells were considered appropriate and healthy pursuits for ladies in mid-Victorian England.

The comet shown in the sky is Donati's comet, the largest and brightest comet ever witnessed, which was at its brightest on 5 October 1858, the date recollected in the painting. Warner has pointed out the reason for its inclusion in Dyce's painting: "But the meaning in this context has more to do with the general importance and implications of science in the Victorian period. The comet and the cliffs represent the vastness of space and time which were being opened up by astronomy and geology and causing so much anxiety and religious controversy. They are a background against which human life itself might seem no more than afternoon's sea-shell gathering" (183). Smith makes an interesting point regarding the significance of the comet in the painting: "The near-invisibility of the comet in Dyce's painting might also appear to cast doubt on the traditional affinity between heavenly and human affairs, and instead nature is seen to operate according to its own invariable laws" (188).

Rosenfeld feels the larger theme of this picture to be a mediation on temporality with geological time denoted by the chalk cliffs of the middle ground, and astrological time inherent in the comet in the sky and the diurnal rhythm implied by the sunset (110). Dyce was an avid amateur scientist and was interested in both geology and astronomy. He would have been attracted by Pegwell Bay's chalk cliffs that were rich in fossils. In the painting Dyce has painted the cliffs in meticulous detail but has shown them to be more grey than the chalky white colour they actually were. Smith has pointed out that Dyce's painting may be intended to draw attention to how the insignificant span of a human's lifetime pales before what the geologic record has to tell us: "The discordant modernity of the painting is often attributed to the flattening effect of the figures who appear superimposed on the setting and the microscopic attention to detail. Dyce's interest in geology, alluded to by the putative self-portrait by the cliffs, is further borne out by his delineation of the flint encrusted, strata and erosion of the chalk…. Set against such ancient and intricately composed matter, Dyce's figures appear insignificant, surrounded as they are by layers and fragments of an immense period of time. [188]

Comparison Between the Watercolour Study and the Finished Oil Painting

While Dyce may have used the watercolour in the Aberdeen Art Gallery as an "aide memoire" in painting the oil version, Jennifer Melville has pointed out the ways in which the two works differ from each other. Their viewpoints differ slightly, with Dyce seeing the chalk cliffs from a position further east in the watercolour, as can noted particularly when comparing Dyce's depiction of the navigation marker on the tide side. Dyce has captured the light effects on the cliffs and pebble beach about an hour earlier in the watercolour. The narrative element of Dyce's family group in the foreground and the figures in the background of the oil are absent in the watercolour and are replaced with two small standing female figures in the centre midground. These women are not of the leisured class but wear simple attire and short skirts signifying they are working women, perhaps on the beach to gather shellfish. Melville therefore concludes: "Thus this painting is an accurate rendition of a particular scene and a particular moment in time and not, as was the finished oil painting, a subject replete with meaning and moral messages" (166).

Other differences between the watercolour and the oil painting can be noted, too. Melville sees that

The fence at the right-hand side is less decayed and in a different position. The geological structures of the cliffs in the finished painting differs from that in the sketch; the caves have become shallower, a prominent gully has replaced the central cave, and the cliffs are higher. However, the most important difference is probably one of mood in a painting in which the visual data are recorded in my minute detail and subjected very deliberately to the imaginative faculty. The emotional effect of the sketch is concentrated in the power of the landscape without weakening the dominance of the natural surroundings, whereas in the painting the figures introduce an element of dream and nostalgia, the consciousness of time passing. [170]

Contemporary Reviews of the Picture

When Pegwell Bay was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1860 the critic of The Art Journal found it to be an unexpected subject for Dyce: "Verily the mere name of the place brings with it a savour of shrimp sauce, and it is here storied in a picture of heart-breaking elaboration. It is about the last subject of which we should have accused the chronicler of King Arthur in the Queen's robing room. The time is evening, deepening twilight, with a sky of singular clearness, but cold withal. The last comet is in the sky, and in the horizon is marked with glowing red the point of the sun's descent. It is most difficult to paint chalk cliffs. They are here brought before us in a low grey tone, which is not cut off at the beach, but continued on the shingle; the whole of the foreground being painted with a truth equal to that of photography" (165).

F. G. Stephens in The Athenaeum had these comments on Dyce's third submission to the Royal Academy exhibition that year, which he felt should have been treated in a broader fashion with less elaboration:

We apply principles of criticism to Mr. Dyce such as we should not think of using in relation to a less earnest artist, and therefore regret that he has not carried out more thoroughly the system of execution evidently aimed at in these works, but more unmistakeably in the third, Pegwell Bay, Kent, a Recollection of October 5, 1858 (141) – an effect just after sun-down, while the sky is perfectly full of light. Very brightly and successfully this is painted, and so brilliantly, indeed, that it ought to have been supported by deeper tone throughout the landscape. The lighted sky is behind the cliffs, but we miss the massed shade in which they would necessarily be; in fact, the eye facing such a light would hardly perceive the immense amount of detail shown in the lines of white chalk before us. The figures keep the tone and tint of open, subdued daylight; whereas, facing the sunset, the reds, as in the lady's dress who stands in front, would be nearly purple; and her figure tell as a whole, opaque, solid and darkly, instead of being bright, thin and transparent, as it is shown to be. A broader consideration of general effect would merit a higher applause than can be given to the elaboration and skilful treatment of individual parts, which is here observable throughout. [653]

The Builder found the work "exceedingly charming" and an effective piece of plein air painting: "So minute a piece (withal so effective), must surely have been painted on the spot" (289). The Illustrated London News found the work to be a curiosity of Pre-Raphaelite precision: "By a rapid descent from the sublime to the droll, we now alight upon Mr. Dyce's third contribution, "Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5, 1858' (141), the date having reference to the period of the comet, which is seen faintly glimmering overhead. This must be pronounced a very curiosity of minute handiwork; every part, from the broad sands, the sun-baked cliffs, and the flat, wide-spreading rocks, to the ladies' red-striped petticoats, and the little shells in their tiny baskets, being painted in the finest of fairylike lines, but with a completeness and exactness which render every microscopic detail palpable to the naked eye" (458).

W. M. Rossetti in The Spectator found it surprising that an artist best known for his figurative works could produce this amazing landscape: "The landscape, Pegwell Bay, by Mr. Dyce, is a far more successful effort, and in this he completely suggests the vague and silent beauty of nature in that glowing evening sky, fading each instant, and retiring to give place to the beauty of the night and the silvery blaze of the comet. We cannot help remarking of this work, so minutely painted, how strange it is to find an artist distinguished for his figure-drawing giving himself up to a work of imitation – a study ever the furthest from high art! (456). The critic of The Saturday Review preferred this work to Dyce's The Man of Sorrows, finding it "if not the better, at any rate the more taking at first sight. In this the landscape is little more than the setting of a most exquisitely-painted group of women and children hunting for curiosities on the shore at low water. The comet faintly marked in the clear evening sky comes in most happily to give individuality to the scene; and the composition is a striking example of how much a painter may gain who takes the trouble to select even the simplest real scene for a background, instead of resting satisfied with ordinary unmeaning kind of filling-up" (678).

Bibliography

Note: The original image on this page was downloaded by George P. Landow from The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002.

Barringer, Tim. The Pre-Raphaelites: Reading the Image. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1998, 79-81.

Dafforne, James. "British Artists: Their Style and Character. No. LI. - William Dyce." The Art Journal New Series VI (1860): 293-96.

"Fine Arts. The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Illustrated London News XXXVI (May 12, 1860): 458.

Melville, Jennifer. William Dyce and the Pre-Raphaelite Vision. Ed. Jennifer Melville. Aberdeen: Aberdeen City Council, 2006, cat. 45,166-67.

Payne, Christina. "The Painting," in "Pegwell Bay, Kent – a Recollection of October 5th 1858 ?1858–60 by William Dyce." Tate Research Publication, 2016. Web. 21 December 2024.

Pegwell Bay - a Recollection of October 5th 1858. Art UK. Web. 21 December 2024.

Pointon, Marcia. "The Representation of Time in Painting: A Study of William Dyce's Pegwell Bay: A Recollection of October 5, 1858" Art History I (March 1978): 99-103.

_____. William Dyce 1806-1864, A Critical Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979.

Rosenfeld, Jason. Pre-Raphaelites Victorian Avant-Garde. London: Tate Publishing, 2012, cat. 82, 110-11.

Rossetti, William Michael. "Fine Arts. The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Spectator XXXIII (May 12, 1860): 456.

"The Royal Academy." The Saturday Review IX (26 May 1860): 677-78.

"The Royal Academy of Arts." The Builder XVIII (12 May 1860): 289-90.

The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Art Journal New Series VI (1 June 1860): 161- 72.

Smith, Alison. Pre-Raphaelite Vision. Truth to Nature. Allen Staley and Christopher Newall Eds. London: Tate Publishing, 2004, cat. 107, 188-89.

Staley, Allen. The Pre-Raphaelite Landscape. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1973.

Stephens, Frederic George. "Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1698 (12 May 1860): 653-55.

Study for "Pegwell Bay - a Recollection of October 5th 1858." Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums. Web. 21 December 2024.

Warner, Malcolm. The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Tate Gallery/Penguin Books, 1984, cat. 106, 182-83.

Created 27 May 2007

Last modified (commentary added) 21 December 2024.