Omnia Vanitas, by William Dyce, R.A. (1806-1864). 1848. Oil on canvas. 24 3/4 x 29 1/2 inches (62.7 x 75 cm). Collection of the Royal Academy of Arts, London, accession no. 03/851. Image reproduced here for the purpose of non-commercial research, courtesy of the Royal Academy of Arts via Art UK. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

The Picture as Social Commentary

Dyce exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1849, no. 43. It was his diploma work and had been accepted by the Royal Academy in 1848. The title comes from Ecclesiastes XII, 8: "Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher; all is vanity." As Jennifer Melville has explained, the intended subject is a moral one:

The beautiful woman who gazes sadly into the distance with her right hand resting on a human skull, is contemplating her own mortality but in so doing is also reflecting on her past life and her morality. She follows a traditional format for depictions of the Penitent Magdalene, who was often accompanied by a skull and portrayed with long flowing hair. She is seductively dressed, and is the closest Dyce ever came to an erotic image, one that is strongly reminiscent of the erotica produced a little earlier by William Etty. The magdalene theme was important for [Marcia] Pointon, who believed that this indicated an intentional contemporary element to the composition. The theme of prostitution was a popular one at the time and was tackled by several of the Pre-Raphaelite artists, most famously by Dyce's protégé, William Holman Hunt in The Awakening Conscience of 1853. [140]

Other Pre-Raphaelite artists with paintings dealing with prostitution included D. G. Rossetti's Found (c.1847-81) and J. R. Spencer Stanhope's Thoughts of the Past (1858-59).

The Royal Academy, which has this work in its collection, comments that Dyce's Omnia Vanitas was "[i]nspired by early Renaissance painting and the work of the 19th-century German Nazarene School. Dyce's composition is classically arranged with the shape of the figure forming a triangle against an uncluttered background. He uses a limited palette of tones but with cool clear colours."

It does seem clear that Dyce intended to portray a contemporary "fallen woman" in this painting: "Inscribed on the frame which is contemporary with the painting are the words 'A Magdalen.' In mid-Victorian, England prostitutes were known as magdalenes and there is evidence in this figure with long, shining hair, her dishevelled linen revealing a finely rounded shoulder, that Dyce was as much concerned with the image of the contemporary fallen woman as with the penitent Mary. If this piece of quasi-erotic biblical allegory, so remote from the precision and directness we have come to expect from Dyce, was created in a bid for recognition from the establishment, then William must have been well satisfied" (Pointon 106-07).

Tim Barringer has also put this work in its Victorian social context, seeing in it, as Pointon and others have done, as "a study of the Penitent Magdalen." He continues, "The luxurious dress of a Titian red and the soft flesh contrast with the coldness of the skull in a surprising memento mori.... Dyce regarded the painting as a demonstration of technical skill and, following custom, donated it to the Royal Academy when he became a member in 1848. The subject, however, was immediately understandable to Victorian society. At the time there was much discussion of so-called "lost women", especially in the High Church circles of which Dyce and the political reformer and future Prime Minister Gladstone were members" (496). It is worth remembering that Dyce was a good friend of Gladstone, who began his campaign to rescue and rehabilitate such women in the 1840s.

Contemporary Reviews of the Picture

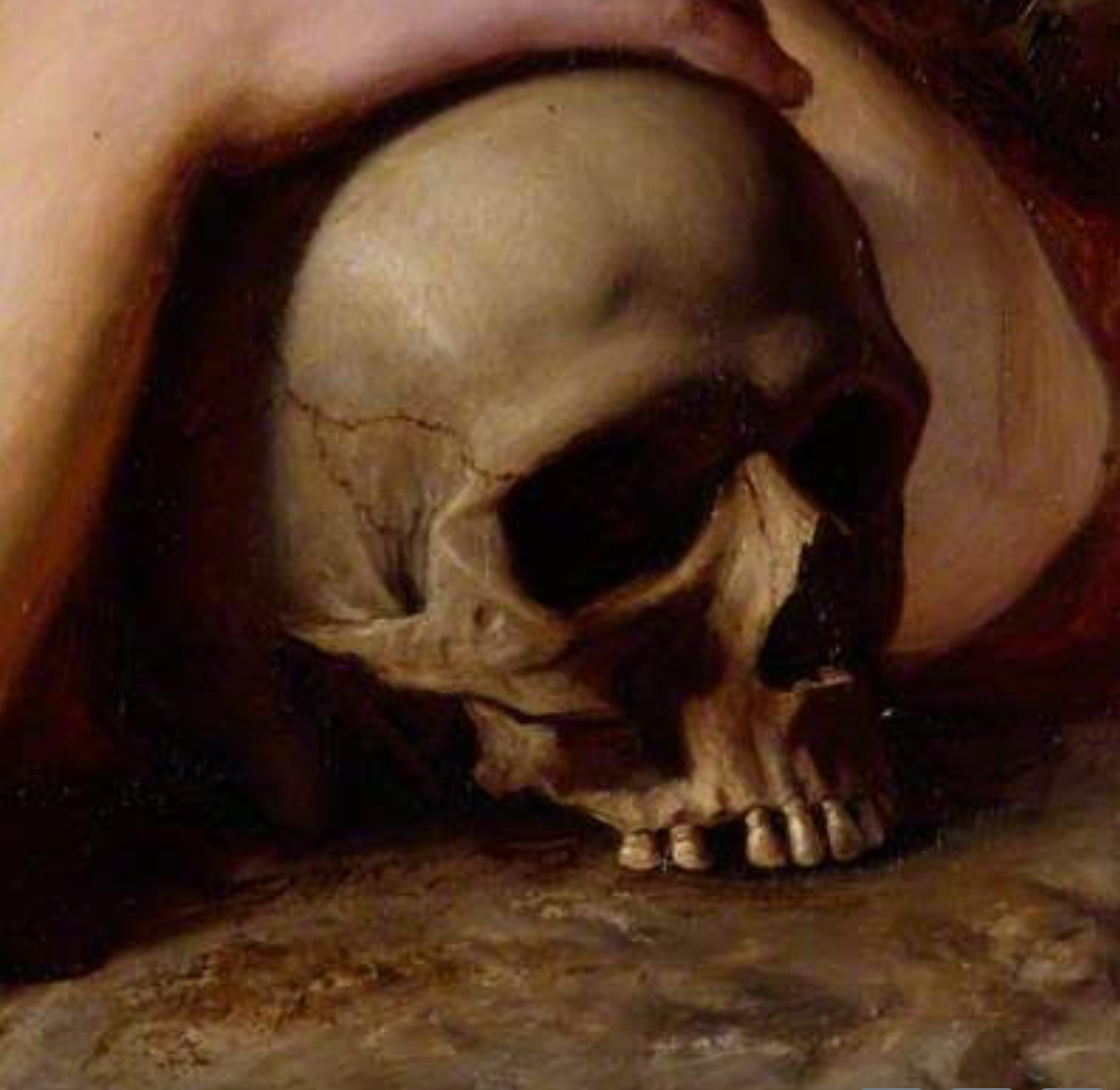

Detail: the skull.

When Omnia Vanitas was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1849, the Art Journal critic felt it was intended for an elevated purpose, describing it as: "A Magdalen, of whom only the head and bust are given; a skull is before her, and she looks upwards with much intensity of expression. The style of this picture is at once severe and elevated; it is a deduction from a pure source without the slightest indication of infirmity of purpose" (166). A reviewer for the Athenaeum felt the draughtsmanship displayed in this work fell below Dyce's usual standards, finding it "less demonstrative than as usual with his works of study at the highest sources. Omnia Vanitas (43) refers rather to the schools on this side of the Apennines, than to the Florentine or Umbrian masters. His Magdalen forms are less correct in their proportions than is customary with this erudite artist" (575).

The Builder admired the painting but also commented unfavourably on the draughtsmanship: "'Omnia Vanitas,' W. Dyce, R.A., represents a female in the zenith of her charms, with a skull on which her hand is resting. It is beautifully painted: the drawing of the arm seems questionable" (230). The Illustrated London News was dismissive too, questioning both its design and execution: "Not very well conceived or very well painted" (346). The Spectator reviwer agreed with the others that this work was not up to Dyce's usual standards, doing "scant justice to his faculties: the countenance is earnest, but the forms are common and the colouring is heavy" (447). For all its undoubted interest, then, this work was rather poorly received.

Bibliography

"The Arts. The Royal Academy." The Spectator XXII (12 May 1849): 447.

Barringer, Tim. Preraffaelliti Rinascimento Moderno [Pre-Raphaelites Modern Renaissance]. Milan: Dario Cimorelli Editore, 2024, cat. II.6, 496.

Dafforne, James. "British Artists: Their Style and Character. No. LI. - William Dyce." The Art Journal New Series VI (1860): 296.

"Exhibition of the Royal Academy of Art. The Illustrated London News XIV (26 May 1849): 345-51.

"Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1127 (2 June 1849): 575-77.

Melville, Jennifer. William Dyce and the Pre-Raphaelite Vision. Ed. Jennifer Melville. Aberdeen: Aberdeen City Council, 2006, cat. 34, 140-41.

Omnia Vanitas. Art UK. Web. 16 December 2024.

Omnia Vanitas. Royal Academy. Web. 16 December 2024.

Pointon, Marcia. William Dyce 1806-1864. A Critical Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979, 106-07.

"The Royal Academy." The Art Journal New Series XI (1 June 1849): 165-76.

"The Royal Academy Exhibition." The Builder VII (19 May 1849): 230-31.

Created 16 December 2024