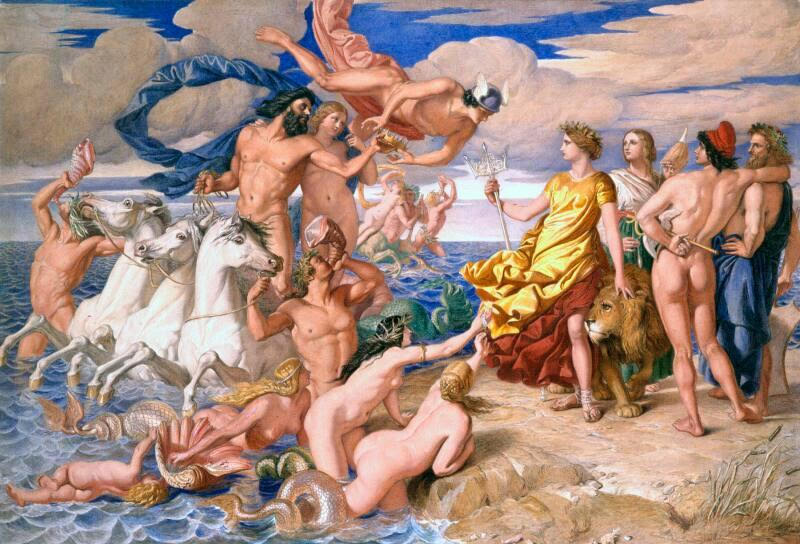

Study for Neptune Resigning to Britannia the Empire of the Sea, by William Dyce, R.A. (1806-1864). 1846-47. Oil on paper laid on board; 12 ½ x 19 ¼ inches (31.7 x 48.7 cm). Private collection. Image courtesy of Sotheby's, London. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

This scheme for a fresco at Osborne House was originally presented to Queen Victoria by Prince Albert in 1847 (details from Sotheby's entry). Photograph courtesy of Sotheby's, originally downloaded by George Landow. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

According to Sotheby's, from Christopher Newall's catalogue entry for the work, "The Italianate villa style of Osborne had initially inspired Dyce to choose a theme from Boccaccio for his fresco but his patrons preferred a subject depicting Neptune and his retinue presenting his crown and other wealthy gifts to the allegorical figure of Britannia, due to the proximity of the sea. Dyce remained inspired by Italian art and borrowed elements from the work of Raphael in his design, specifically from the decorations at the Villa Farnesina in Rome. The tritons blowing conch-bugles and leading the Hippocampi that draw Neptune’s chariot, are very similar to figures in the Rome ceiling."

As far as the general effect goes, nothing could better illustrate the British pride in the Royal Navy in these years, despite the difficulties in funding it. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert took a particular interest in the navy. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Commentary by Dennis T. Lanigan

The oil sketch was Dyce's only exhibit at the Royal Academy in 1847, no. 42. It was purchased at the exhibition by Lord Lansdowne. Prince Albert had always been highly supportive of Dyce's work, both privately and publicly. The fresco, a maritime subject celebrating Britain’s command of the oceans, is still present at Osborne House and can be seen on the wall above the stairwell. An oil sketch for the subject, once in the Forbes Collection, sold at Sotheby’s, London, in 2018 and a watercolour and gouache study is in the collection of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums.While the sketch entered the Forbes Collection, and was sold at Sotheby's in 2018, a watercolour and gouache study is in the collection of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums.

Study for Neptune Resigning the Empire of the Sea to Britannia. 1846-47. Watercolour and gouache on paper. 16 3/8 x 24 inches (41.6 x 61 cm). Collection of the Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums, object no. ABDAG010741. Image courtesy of Aberdeen Art Gallery and Museums under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial licence (CC BY-NC). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

When the oil sketch came up for auction at Sotheby's, Christopher Newall described it as probably having been executed

to show the Royal couple how the fresco for the staircase at their Isle of Wight residence would look when complete. The finished wall painting, completed in the same year, measures seventeen feet wide by ten feet high and differs only in small details from the present work. On 13 January 1847, following a lunch with the Queen and Prince, Dyce told his fellow artist Charles West Cope that his design had been well-received; "Prince thought it rather nude; the Queen, however, said not at all." This remark demonstrates Queen Victoria's lack of coyness in her artistic tastes. The dozen towering nudes, including the God of the Oceans Neptune and his cohort Amphitrite, accompanied by tritons and sea-nymphs, a putto and centaur, delighted the Queen but Dyce reported that "The nursery maids and French governesses have been sadly scandalised by the nudities." The Prince took a very active interest in the painting of the fresco and in another letter to Cope, Dyce wrote of his frustration; "… when you are about to paint a sky seventeen feet long by some five feet broad, I don't advise you to have a Prince looking in upon you every ten minutes or so – or when you are going to trace an outline to obtain the assistance of the said Prince and an Archduke Constantine to hold up your tracing to the wall, as I have had. It is very polite, condescending, and so forth, very amusing to Princes and Archdukes, but rather embarrassing to the artist." [50]

Emily Thomson, in discussing the more finished watercolour study at Aberdeen, points out that the watercolour sketch follows the initial oil sketch that Dyce had shown to Prince Albert and Queen Victoria for their approval: "Dyce must have been happy with it, for calibrations down the side of the paper indicate that it was squared up for transferral to the cartoon. The cartoon would have subsequently been transferred directly to the wall, for Dyce, unlike other artists, rarely deviated from his cartoon when completing a fresco. The scene illustrates the imminent coronation of Britannia by Mercury, who bridges the gap between land and sea, and Neptune and Britannia. In comparison to the Forbes Collection sketch the triumphant stance of Britannia exudes a greater majesty. This majesty is reinforced by the figures surrounding her, their attributes signifying the glory of Britannia. The figures represent British industry. The female figure holds a distaff, relating to textile production, and the male figure to the extreme right of the composition leans on a rudder symbolizing navigation. The figure with his back to the spectator carries Mercury's caduceus, a symbol of peace, eloquence and reason, again in reference to Britannia virtues" (120).

Contemporary Reviews of the Picture

When the oil sketch was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1847 a reviewer for The Athenaeum praised the fact that Dyce was not always painting under the influence of early Renaissance art and was showing an increased versatility: "Mr. Dyce's design for the fresco at Osborne House, Neptune assigning to Britannia the Empire of the Sea (42), is a declaration that this artist will not always be satisfied to practice under the influence of early art. An improved originality here perceptible augurs that when the picture itself shall be completed, he will have vindicated himself from the charge of a disposition to entertain narrow and isolated views. There is much refinement and beauty in this carefully studied sketch" (495). The Illustrated London News did not like Dyce's representation of either Britannia or the British Lion: "Neptune Assigning to Britannia the Empire of the Sea . W. Dyce. This is Mr. Dyce's sketch for a picture to be painted in fresco at Osborne House. The general composition is extremely careful, and some of the colouring – the flesh particularly, of the female attendants upon Neptune – warm and truthful. The figure of Britannia is a failure – she is a silly country lass...Her lion, too, is a sorry representation of the monarch of the forest" (297; one wonders if Dyce had read ths review, as the two figures most markedly altered from the oil sketch in the final fresco were those of Britannia and the lion).

The critic of The Art-Union praised the colour and style of the composition and explained it as

a small oil sketch for a fresco which is to be painted at Osborne House for her Majesty. Upon the proper right of the composition Neptune has approached the shore, accompanied by Amphitrite, and ministered onto by the usual company of marine attendants. Britannia, as yet young, is represented by a figure of much sweetness and simplicity, fitly representing the political infancy of Britain. She is attired in red and yellow drapery, – already holds the trident, and is about to receive from the hands of Mercury the crown of Empire. By her side is the British lion, and near her a figure representing liberty as wearing the Phrygian cap, and another more aged man whose attribute is the helm. This sketch is brilliant in colour, and original in style; the narrative is so perspicuous as to require no descriptive title; and yet it is most probable that, on a larger scale, the composition will acquire yet higher qualities. [186]

The Spectator's critic reviewed the painting most extensively, although his review was somewhat mixed, particularly because he disliked allegory as an art form. Among the few works that drew upon poetry or mythology for their subjects, this critic felt that Dyce's was definitely the most striking, exhibiting, he declared, "more mastery of art than any picture in the collection"; still, he considered

allegory to be a detestable class of subjects for painting: allegory is a grave quibble, and a picture resting on such a basis is stamped by its very origin with unreality. it is a picture without a subject; because the subject is something to be constructed out of the semblance of one – that counterfeit to be set aside by the spectator as a triviality. It is attempting to depict what cannot be represented by visual objects. In this picture, Neptune in his watery chariot has driven close to the margin of the land, where he pulls up; he holds out a crown, which the flying Mercury, as the genius of Commerce, takes from his hand, and conveys to Britannia. Sea-Nymphs also lean over the margin of the land, and offer to Britannia the precious products of the deep. Behind Britannia are three figures, indicated by their attributes to be the geniuses of Manufacture, Trade, and Navigation. All this is very intelligible, on a conventional interpretation; but it supplies no proper action for the picture. There is life and action in the design: Neptune is excellent – grand, vigorous, and energetic; in Amphitrite, who looks on approving, and in Britannia, are indicated two female forms of much beauty and dignity. The Sea-Nymphs also are beautiful, but not unexceptionable in style. It is most usual, we think, with artists who paint ladies that terminate in fish, to make the junction of the of the several natures at the hips: Mr. Dyce, not without precedent, continues the human form to a lower point; but in extending the human part the monstrous is rendered more glaring: in fact, there is a considerable breach of verisimilitude in suggesting two modes of locomotion. The human aspect of the Nymphs in Mr. Dyce's sketch, who look like bathers come to show Britannia something which they have found at the bottom of the water, raises familiar ideas unfit for the abstract classism of the subject. The defects which we have pointed out might pass in a picture of less merit: they are apparent chiefly through the vigour and skill of the artist in giving so much life and reality to the figures: that sort of reality jars against the unreality of the dry abstraction in the allegory. As an assemblage of tints, the sketch is very pleasing: the colours are lively; although the canvas is full of figures, the scene is open – an airy space. Mr. Dyce has the faculty of imagination – of really conceiving the event and the scene before he paints them; and he has promise of powers more like those possessed by the great painters than any artist we have in this country. [521-22]

Allegory was not an issue for James Dafforne in The Art Journal. In 1860, when reviewing Dyce's career as a whole, he admired both the conception and the spirited execution of this sketch. He recognised that Prince Albert's choice of subject was unlikely to be have been to the artist's own taste, but desribed it in appreciative detail:

On the left of the composition, Neptune, accompanied by Amphitrite, is approaching the shore in a car driven by three horses; they are surrounded by marine attendants, male and female. Immediately above them Mercury is seen floating in the air, and holding forth his hands to receive the crown from the sea-god, and to place it on the brow of Britannia. The conception of this group is very fine, and it is most spirited in the execution. To the right, on the shore, which is slightly elevated above the level of the sea, is Britannia, clad in red and yellow draperies, flowing in the wind; her attendance are three personages of various ages, and a noble lion: one of the figures, a young female, holds a distaff in her hand, and represents Industry; another, a young man, wears the scarlet cap of Liberty, and represents Commerce; and the third, somewhat advanced in years, is leaning on a rudder, and symbolizes Navigation. [296].

Dafforne enjoyed the "rich and brilliant" clouring," but was dubious about one element of it: "the deep blue drapery behind the shoulders of Neptune is so intense as to almost overpower everything else; we should prefer seeing it less obtrusive" (296).

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Cope, Charles Henry. Reminiscences of Charles West Cope, RA, by His Son. London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1891, 167 & 171-73.

Dafforne, James. "British Artists: Their Style and Character. No. LI. - William Dyce." The Art Journal New Series VI (1860): 293-96.

"Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Illustrated London News X (8 May 1847): 296-98.

"The Exhibition of the Royal Academy." The Art-Union IX (1 June 1847): 185-200.

"Fine Art Gossip." The Athenaeum No. 1002 (9 January 1847): 50-51.

"Fine Arts. Royal Academy." The Athenaeum No. 1019 (8 May 1847): 494-96.

"Fine Arts. The Royal Academy: Historical Pictures." The Spectator XX (May 29, 1847): 521-22.

Neptune Resigning the Empire of the Sea to Britannia . Aberdeen Archives, Gallery & Museums. Web. 15 December 2024.

Neptune Resigning to Britannia the Empire of the Sea. Sotheby's. Web. 15 December 2024.

Newall, Christopher. Victorian, Pre-Raphaelite & British Impressionist Art. London: Sotheby's (July 12, 2018): lot 37, 50-51.

Pointon, Marcia. William Dyce 1806-1864. A Critical Biography. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979, 93-95.

Thomson, Emily Hope. William Dyce and the Pre-Raphaelite Vision. Ed. Jennifer Melville. Aberdeen: Aberdeen City Council, 2006, cat. 24, 120-121.

Created 25 October 2018

Last modified (commentary added) 15 December 2024