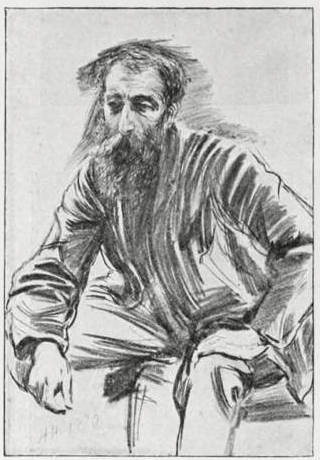

Hubert von Herkomer's portrait sketch of Calderon.

Forty-seven years ago I was making a drawing from an antique in the British Museum, when a young man, with a highly intelligent face, dark eyes, and a slight black moustache, looked over my shoulder for a minute or two and then addressed me in French. I had not long returned from Paris, which fact must have been perceived by that quick-witted youth of seventeen. We entered into conversation (in French) and found that we both had the desire to become artists, and also that we both lived in St. John's Wood — he, in Marlborough Road, and I, in Marlborough Place. What more natural than that we should walk home together, after our day's work was finished at the Museum? In a very short time we became fast friends; and although we were each respectively living under the paternal roof, we soon began to invite each other to tea, and spent pleasant evenings together, sometimes at his home and sometimes at mine. The young man's name was Philip Hermogenes Calderon.

He introduced me to his father, the Rev. Juan Calderon, Professor of Spanish Literature at King's College, an elderly gentleman of a strongly-marked Spanish type; and to his mother, a French lady, who was devoted to her only son. Like many other artists, Calderon did not deliberately choose bis career from the first: it came upon him with an imperious mandate. He studied engineering, and the opportunities afforded by the continual presence of drawing materials led him to devote more of his time to art than science.

Calderon went to Leigh's School of Art in Newman Street, where he met Henry Stacy Marks, Walter Thornbury — who afterwards became the well-known author — and several others who have since made their names. From Leigh's he went to Paris with his friend Marks, where he studied, for a year, under M. Picot. He then returned to London, having finished his schooling, but not his education in art. He and Marks were welcomed back by a little band of young artists, Fred Walker amongst them, who had formed themselves into a brotherhood called “The Clique,” and which somehow looked upon Calderon as their chief, for he had a personality that persuaded and even commanded. He was tall and good-looking — was, as it were, a Spanish gentleman translated into English; very witty, he had an uncompromising spirit and withal a most fascinating manner; in fact, he could be severe and unflinching, and yet as tender as a child.

His earlier pictures betrayed a good deal of this hardness in the painting, but the tenderness of his nature became evident when, having conquered the first difficulties of his craft, he produced such works as the Demande en Mariage — a delightful representation of an old sexton reading a letter, which his daughter has just brought him from her lover, whilst the latter is waiting for the verdict, outside, on the belfry stairs; and After the Battle, where a party of soldiers and a drummer-boy have entered a ruined cottage, in which everything seems to have been destroyed by cannon-shot except a solitary child, that sits there unharmed. The look of astonishment and gentleness on the faces of the veterans whose trade is to slay, is a masterpiece of expression, and an excellent rendering of the apt quotation, "Men ne'er spend their fury on a child.

Such pictures as these showed that Calderon could both conceive and paint beautiful things that were not only pleasing to the eye of the connoisseur but could reach to the hearts of all. However, I have no intention of criticising or praising, or overrating or underrating the works of Calderon; time will pronounce its verdict on them. I feel confident, however, that many of his pictures would make most popular engravings. A small one of After the Battle was published some yeare ago in The Art Journal, but I think a larger and stronger one would certainly be welcomed.

Calderon exhibited his first picture at the Academy in 1850. I remember it well, for we both made sketches of the same subject, which was, "By the waters of Babylon there we sat down; yea, we wept when we remembered Zion.

For several years he worked on without much success, sending only another picture to the Royal Academy in 1855, with also a religious quotation, namely, Thy will be done.

Broken Vows.

He was in a doubtful state of mind, and felt almost that he would have to go back to engineering drawing, in which he had had some little experience, or apply for some clerkship in the City. He said, however, that he would make one more effort, and would paint a picture that should decide his fate. The subject he chose was Broken Vows, probably suggested by Longfellow, a poet for whom, in those days, he had a great liking. And the young lady who sat for his principal figure was his future wife — even his wedding depended upon the success of this production. I remember with what interest his nearest friends watched the progress of the work, none having any doubt that the desired object would be attained by it, ami that P. H. Calderon would not have to go into the City to seek employment.

There was great excitement in those days among the young artists, for a change was coming over the school through the influence of Millais, Holman Hunt, and others of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The love of Nature was ousting the love of conventionalism, and this was shown in the careful delineation of the minutest detail of leaf and flower, rock and stone, and sunlight and sun-shadows. Broken Vows was not only a subject likely to be popular, since it represented a young lady who accidentally discovers her lover to be faithless, but was painted in the new spirit; and without doubt the heart of the painter was in his work, for he not only depicted the ivy leaves, the old wall, and the grey palings with loving care, but it may be supposed that he was still more interested in his fair sitter. The picture was finished, was well received by the Academy and the public, was sold, and was engraved. The battle was won! Henceforth the finances of a City firm, or the drawings in an engineer's office, would have to do without the assistance of Philip Hermogenes Calderon, the descendant of Don Pedro Calderon de la Barca, the great Spanish poet.

"Ce n'est que le premier pas qui coute, and after this first success in 1857 others soon followed. A great improvement in his art was evident, and he put more dramatic feeling — that is to say, more human nature — into his compositions, as shown by his Gaoler's Daughter — a scene from the French Revolution — Flora Macdonald's Farewell to Charles Edward, and French Peasants finding their Stolen Child at a Country Fair. This picture was painted in 1859.

He was elected A.R.A. in 1864 — the same year, and at the same time, as Frederick Leighton. Nor has the Royal Academy ever elected two men who have been more devoted to its service. Those student days in Paris with his friend Marco, when they had rather to rough it — those doleful days of doubt when he feared he would have to give up all thoughts of art — were all past; he was in a pleasant and lofty studio in Marlbrough Place, built at his own expense, and there were pictures on the easel that commanded four figures. His painting partook of the happy times, his touch was firm and confident, lhs colour joyous, and he showed that in dexterity at least he was not to be outdone. Among other things he painted, chiefly for amusement, or as a “fetch,” as we used to call it, a portrait of his wife, life-size, standing in a doorway with her hand on the door-handle and her foot on the step, looking back over her shoulder as though she were quitting the room. The picture was placed against the panelled wall of the studio, and was such a perfect illusion that it looked, not like a picture, but a reality — so much so that genial Tom Landseer, the engraver, who called one day, made a most profound bow to it, and, addressing the effigy, said, “Pray do not leave us, madam.”

There were frequent and merry gatherings in this studio. Sometimes of an evening the chests of costumes would be ransacked by The Clique in order to amuse the ladies in the drawing-room with impromptu acting charades, which were anything but dumb show, our old friend Marco occhsionally outdoing the deepest-dyed villain of a transpontine theatre: and each member of the party, having his special line of nonsense, would add to the variety of the performance, which was always rewarded with plenty of laughter. On other occasions they would sit round the card-table and play at Preference Whist, a very favourite game of Calderon's, or they would often meet there on a fine Sunday morning, and hence take their way through West End Line, then a winding and pretty country road, shaded by overhanging trees, with fields on either side, and walk sometimes as far as Hampstead Heath to breathe the air and at the same time to tell the last good story, or talk over the state of the arts.

A mere list of the titles of an artist's works is only suitable for the sale-room, for it conveys nothing to an ordinary reader. But if we can follow a painter's progress by recalling a few of his principal pictures, it may be interesting. I have referred to Demande en Mariage and After the Battle, which were original subjects — that is, the artist's own inventions. So also, to a certain extent, was Katharine of Aragon and her Women at Work, painted at Hampton Court. This was followed in 1861 by The British Embassy in Paris on the Day of the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, a remarkable picture, depicting a strong dramatic situation with great power and truth.

This was followed in 1864 by The Burial of John Hampden, June, 1643, or rather John Hampden, etc., for I remember the purchaser of the work objected to the word burial. This was a very poetical conception. In 1866 Calderon justified his election as Associate of the Royal Academy by his picture of a child-queen with a long train passing through a tapestried gallery, heralded by trumpeters and followed by stately and beautiful women in the rich costume of the fifteenth century. This he called Her Most High, Noble, and Puissant Grace. It was another of the artist's own inventions, and was not only a success at the Academy, but in the Paris International Exhibition the year following, where it obtained the only gold medal awarded to English art. This work is full of excellence, both of drawing and colour and presentment of character. Some of the female heads are extremely beautiful, for Calderon could paint a beautiful and distinguished face and a very lovable one.

In 1867 he exhibited Home after Victory, another stirring, semi-historical subject, the background of which was painted from the courtyard of Hever Castle, in Kent, where he, with Mr. W. F. Yeames (now R.A.), David Wynfield, and all their family belongings, passed the summer of 1861, not only forming a sort of large happy family in themselves, but inviting their friends and enterthining them right royally.

Here, too, Calderon painted his picture called Whither? which now hangs in the Diploma gallery at Burlington House, for he was elected a Royal Academician three years after he became an Associate, and some little time before Lord Leighton.

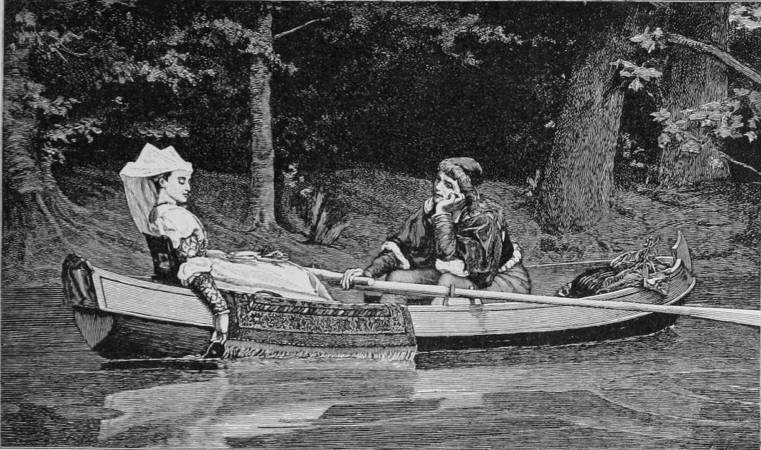

Sighing his Soul into his Lady's Face

Among this artist's sincere friends and admirers was Mr. Schwabe, who formed a collection of English pictures which he presented to his native town of Hamburg. Among them were several of Calderon's best works, such as Sighing his Soul into his Lady's Face (here reproduced), the sweet little head called Constance, and a portrait of a handsome Irish girl holding a basket of roses, which he called La Gloire de Dijon.

Another friend and admirer was Mr. John Aird, the present owner of a goodly series of Calderon's more decorative works, such as The Olive and The Vine, The Flowers of the Earth, and four or live others of a similar character which adorn the walls of this generous patron's dining-room.

These pictures show the painter to the greatest advantage. They fulfil one of the missions of art, which is to be decorative and enjoyable without insisting too much on raising our minds or teachiug us moral lessons, and are entirely devoid of allectation and eccentricity. They are frank, bold, strong, healthy pictures such as Paul Veronese might have delighted in, but without being in the least imitative or inspired by anything but the artist's own feeling and view of nature. They account to me for the immense enjoyment he took in the many fine works we saw during a trip we took to Italy some sixteen or seventeen years ago. They were painted in his house in Grove End Road, where there was not only a fine studio, but ample room in the grounds for lawn-tennis and such-like games, in which Calderon himself took the greatest pleasure. He moved from there to occupy the rooms in Burlington House, set apart for the keeper of the Academy, whith responsible office he undertook in 1887.

Left: St. Elizabeth of Hungary. Right: Ariadne. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

Devoting himself with energy to his new labour, he yet had time to produce some of his best pictures, such as Aphrodite, Andromeda, Ariadne, St. Elizabeth of Hungary, and some beautiful heads. But still his time was too much taken up for him to paint much, and lately ill-health, though it did not paralyse his hand, prevented him almost from working at all. To one of his pictures called Home he puts the quotation:

But things like this you know must be

After a famous victory.

Calderon had fought the battle of life and won, so far as mortal can. He had done his duty in that state of life to which he had been called. On all sides one hears from those who have had the best opportunity of judging him the most kindly expressions concerning him. He has improved the schools both in character and in the insinution given; he was exactly the man to hold such a position, strict in discipline yet gracious in manner. Indeed, only the day before his death I met one of the curators of the schools, who told me that he and his collaborators and the students were anxious to send him a note, signed by them all, testifying to their gratitude and kind feeling towards him with which he had inspired them during his keepership. They had only hesitated to send him such a document because it seemed like bidding him farewell, whereas they still looked forward to seeing him again. At all events, I promised to convey their message either personally or otherwise; but alas! it was too late, for when I called the next day Calderon had passed away, and had resigned his keepership for ever.

I feel that this short notice of so eminent a man as Philip H. Calderon is very inadequate. It has been written not without much pain to myself, as every word reminds me of the great loss we have sustained by his death.

Bibliography

Storey, G. A., A. R. A. “Philip Hermogenes Calderon, A. R. A. (1833-98).” Magazine of Art. 22 (November 1897-October 1898): 446-52. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of Toronto Library. Web. 28 October 2014.

Last modified 28 October 2014