In this essay I shall examine the evidence linking John Brett and Christina Rossetti and also a portrait of her by Brett included in the current Tate exhibition Pre-Raphaelites: Victorian Avante Garde. The evidence that Brett proposed to Christina Rossetti at some time in the late 1850s comes from two much later sources: Violet Hunt notes that he had told her he had proposed to Christina Rossetti but had been rejected (272). In addition we have William Michael Rossetti’s comment concerning her poem ‘No Thank you John’, published in her first collection Goblin Market and Other Poems (1862), in which she rejects the unwanted advances of an otherwise unidentified John.

I never said I loved you, John:

Why will you tease me day by day,

And wax a weariness to think upon

With always "do" and "pray"?

You Know I never loved you, John;

No fault of mine made me your toast:

Why will you haunt me with a face as wan

As shows an hour-old ghost?

I dare say Meg or Moll would take

Pity upon you, if you'd ask:

And pray don't remain single for my sake

Who can't perform the task.

The poem concludes:

Here's friendship for you if you like; but love, —

No, thank you, John.

In his Family Letters of Christina Rossetti (1908) William Michael writes ‘Yet John was not absolutely mythical for, in one of her volumes which I possess, Christina made a pencil jotting, ‘The original John was obnoxious because he never gave scope for ‘No, thank you’. This John was, I am sure the marine painter John Brett who (at a date long antecedent, say 1852) had appeared to be somewhat smitten with Christina…’ (54).

The date William Michael suggests is impossibly early since Brett’s very detailed diaries covering the period 1851-mid 1854 make no mention of the Rossettis. For much of this period he was a penniless struggling student at the Royal Academy Schools who would not have been in a position to propose marriage. The relationship is much more likely to date from the period 1856 to early 1858, by which time he had moved close to the Pre-Raphaelite Movement. Thus he contributed to the Russell Place Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition of July 1857. But William Michael’s identification of the subject together with the atypically caustic, very personal tone of the poem suggests it relates to a real incident. Indeed, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who must also have been aware of John’s identity, tried to dissuade her from including the Work in her Collected Poems on the grounds that it was ‘utterly foreign to your primary impulses’ (Letters III, 1380).

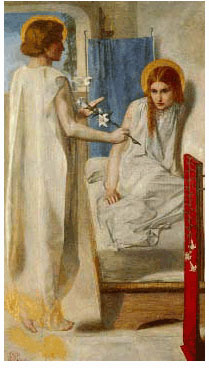

Christina Rossetti. [Click on image to enlarge it.]

One further piece of evidence is provided by a small, unfinished oil portrait of Christina Rossetti by Brett. Although it is not inscribed by Brett himself it carries an inscription on the reverse by his grand-daughter, Winifred Watson, ‘Christina Rossetti? Mickleham 1857. Christina Rosseti?’ It is a fascinating and mysterious work for a number of reasons. Although Brett was an accomplished portrait artist this stands out among his portraits with its strongly Pre-Raphaelite character, both in terms of its technique and its symbolism. This would also support the ‘Mickleham 1857’ dating given it was there that he painted his Pre-Raphaelite masterpiece The Stonebreaker.

It is painted with a minute and detailed precision on a white ground, a typically Pre-Raphaelite technique employed to create brilliant colour effects. (Payne, 2010). In his Oct 7 1857 letter to his sister Rosa Brett, also a Pre-Raphaelite artist, Brett stresses the importance of colour and advises her to ‘always paint things with colour in them’ (Hickox, 1995). The background is painted in an intense blue vermillion, a pigment employed by the medieval and early Renaissance artists favoured by the Pre-Raphaelites.

As regards the portrait’s symbolic meaning, much depends on an interpretation of the prominent feather, beautifully painted with a Ruskinian fidelity to nature (Charles Brett, 2005). Jan Marsh (1994) has suggested this may symbolise a quill representing Christina’s vocation as a writer. While this is possible, it ignores the fact that the work is unfinished and one must try to imagine the completed picture. Thus another feather seems to be clearly outlined behind Christina’s head and another object to her left. One can suppose that the finished portrait would have been highly decorative in much the same way as Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s portraits and watercolours of this period, which may have served as Brett’s model. Given that both Christiana and Brett, at least in this period, were deeply religious one it is likely that religious symbolism of some kind may have been intended. As she stares into space, Christiana has almost the appearance of a Botticelli angel. Could the feather(s) have been intended to symbolise angels’ wings?

The Girlhood of the Virgin Mary and The Annunciation

Earlier Dante Gabriel had used Christiana as a model for the Virgin Mary in both The Girlhood of the Virgin Mary and The Annunciation. Interestingly the feather appears to be a turkey’s tail feather displaying the bird’s very characteristic white fringe. The nearest, perhaps, Brett could get to Dante Gabriel’s exotic peacocks in a rural setting?

Whatever the feather’s symbolism, there can be no doubt that Brett was very alive to the issue of female genius in literature in this year and he would certainly have been aware of Christina’s literary aspirations, even if she remained still largely unpublished. In his letter to Rosa he notes that he is illustrating Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s poem Aurora Leigh: ‘I can’t tell you how much I admire it-it is far beyond admiration-a Divine book.’ It may be significant that of the three extant sketches one, dated Oct 22, illustrates the key moment in Book 2 where Aurora Leigh crowns herself in recognition of her own poetic genius: ‘I drew a wreath drenched blinding me with dew across my brow and fastening it behind’.

Could Brett have identified himself with Romney, the central male figure in the poem, with whom Aurora Leigh eventually falls in love? Unfortunately ‘No thank you John’ relates to the earlier episode in the poem, depicted by Arthur Hughes, in which Aurora Leigh rejects Romney. Indeed, one may wonder whether Christina had this episode in mind when she composed her poem.

Bibliography

Brett, Charles. 'John Brett and Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing.' The Burlington Magazine, September 2005.

The letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Eds. O Doughy and J.R. Wahl. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1967.

Hickox, Michael. 'John Brett's The Stonebreaker. The Review of The Pre-Raphaelite Society (Spring 1995).

Hunt, Violet. The Wife of Rossetti. London: 1932.

Marsh, Jan. Christina Rossetti. London: Jonathan Cape, 1994.

Payne, Christiana. Objects of Affection; The Pre-Raphaelite Portraits of John Brett. London: Sansom and Co, 2010.

Christiana Payne. John Brett, Pre-Raphaelite landscape painter. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2012.

Rossetti, William Michael. The family letters of Christina Georgina Rossetti. London: 1908.

Last modified 20 September 2012