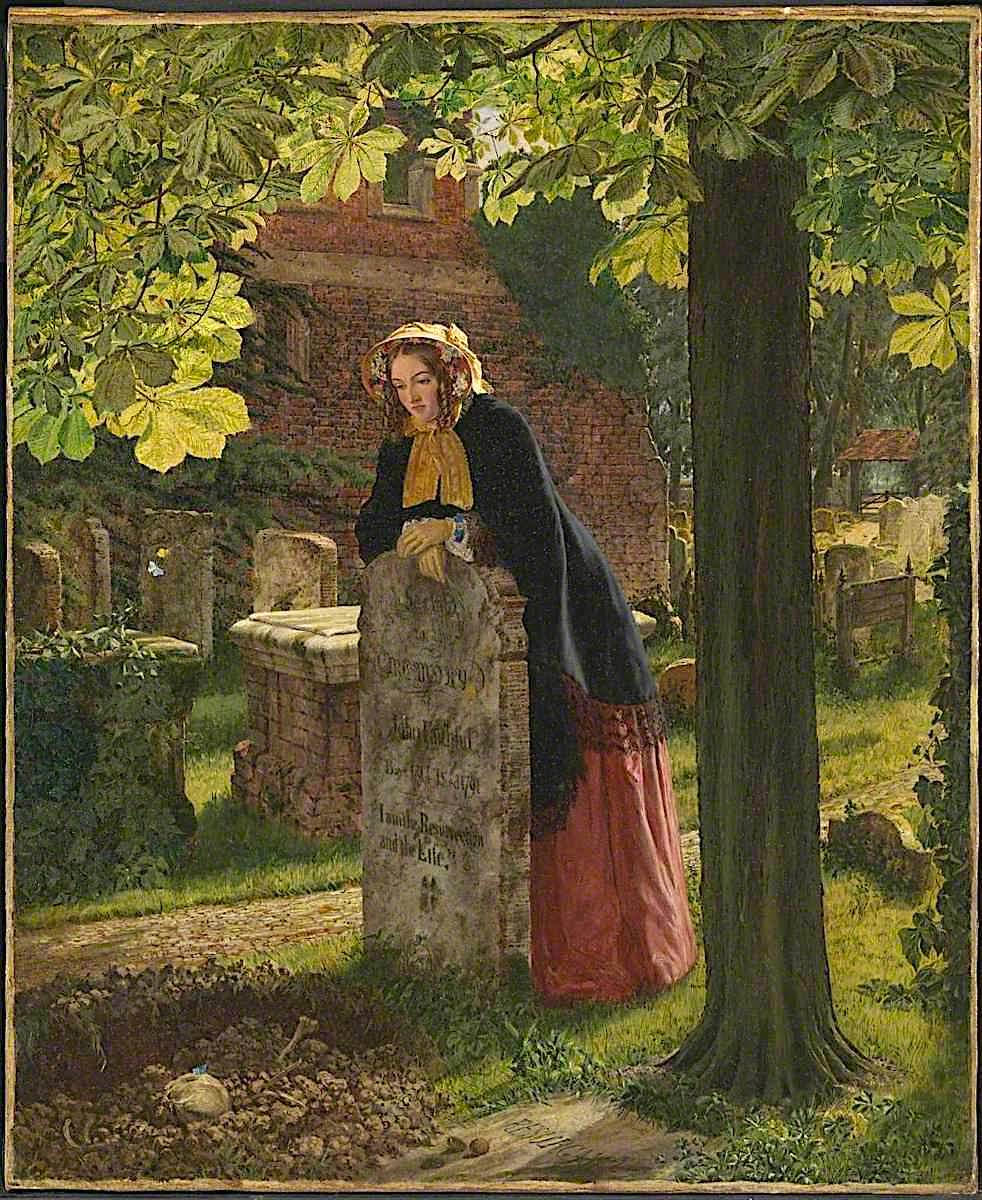

The Doubt: "Can These Dry Bones Live?" . Oil on canvas. 23 1/2 x 19 9/16 inches (59.7 x 49.7 cm). Collection of the Tate Britain, reference no. NO3592. Image via Art UK on the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (CC BY-NC-ND).

Bowler exhibited this painting at the Royal Academy in 1855, no. 644, and then later at the International Exhibition held at South Kensington in London in 1862. This is Bowler's best-known work, but despite its obvious quality, he was never able to sell it. His lack of financial success as an artist likely influenced his decision to become a teacher and art administrator. His son Henry Archer Bowler eventually donated this painting to the Tate Gallery in 1921.

The painting is dated 25 Aug. 1854 on the stretcher. It was obviously influenced by the first phase of Pre-Raphaelitism as seen in its brilliant colouration and lighting effects and the sharp realistic details of the foliage, tombstones, the brick walls of the church, and the young woman's costume.

The quotation in the title "can these dry bones live" is derived from Ezekiel Chapter 37 in which God shows Ezekiel the valley of dry bones: "He asked me, 'Son of man, can these bones live?' I said, 'O Sovereign Lord, you alone know.' Then he said to me, "Prophesy to these bones and say to them, 'Dry bones, hear the word of the LORD! This is what the Sovereign Lord says to these bones: I will make breath enter you, and you will come to life.'" In Bowler's painting the question of whether these dry bones can live is posed by a young woman who leans on a tombstone inscribed, "Sacred [to the memory of] John Faithful. I am the Resurrection and the Life." She looks at his exposed skull and bones, including the distal end of a femur and a couple of ribs, of the man who had died more than sixty years earlier in 1791. Based on the expression on her face the young woman appears to have some religious doubts as to the possibility of the resurrection, with the dead coming back to life on the Day of Judgment. The Victorian period was a time of religious uncertainty with geological discoveries and the writings of Charles Darwin regarding evolution challanging the traditional teachings of the Bible. Bowler, however, has balanced these doubts with two symbols of new life and resurrection – "The germinating chestnut on the flat stone, and the butterfly which sits on the skull" (Gilmartin 207). Leslie Parris had earlier pointed out the significance of these two symbols: "A butterfly, traditional symbol of Resurrection, perches on Faithful's skull. Whether the young lady's doubts are answered, we are not told, though her expressions suggests that they may not be. On the stone at the foot of the tree Bowler depicts a germinating chestnut: his own symbol, perhaps, of natural regeneration and an alternative to the supernatural resurrection proclaimed on the standing stone" (130).

The historian Thomas Laquer, in his book The Work of the Dead, discusses the shifts in the treatment of the dead in the Victorian period where there was often the relocation of the dead from intramural churchyards, as in Bowler's painting, to extramural cemeteries where the graves were better maintained:

Henry Alexander Bowler's The Doubt: "Can These Dry Bones Live?" was painted in 1855 as a meditation on Tennyson's In Memoriam. A young woman is standing amidst the genteel disrepair of what appears to be a substantial country churchyard (but actually is the churchyard of the London suburb of Stoke Newington). The box tomb on her right has lost its siding, exposing the brick vault beneath; this is the sort of shelter that sparked late eighteenth-century litigation, an effort that went against the nature of the place, that somehow tried to bring order to an individual grave by claiming for it a permanence that some opposed. The stone behind her has sunk almost out of sight; further back, an old-fashioned and short-lived grave board with elaborately carved posts running laterally along the body beneath is visible among a picturesque array of variously angled slabs. She rests her arms on the gravestone of John Faithful and looks onto the disturbed earth of the grave — there is no hint why it is in this condition, but it is almost a trope of churchyard representation. More specifically, she contemplates the skull that is lying there and the femur and bits of ribs that are poking out of the ground. This would have been unthinkable in the new regime of the cemetery. The red brick buttresses and a few windows of the church building itself stand out as if to make the point of a historical continuity of the Christian community of the living and the dead, represented by the field of markers in various stages of decay—its past, by the church that serves the living, and by the visit itself. John Faithful died in 1791, and the woman's costume makes clear that the scene we are witnessing occurred sixty years later, in the 1850s. The stark fact of death is counterpoised with the promise of everlasting life: I AM THE RESURRECTION AND THE LIFE, it says on Faithful's stone, which we, but not the young woman, see; RESURGAM (I shall rise again) is written on the slab nestled in the ground at the foot of a large, very much alive and growing chestnut tree. Although topologically specific, the painting's landscape, like that in Nicolas Poussin's Et in Arcadia ego or the imagined landscape where Ezekiel confronted "dry bones," is prototypical: the universal country churchyard. [138-39]

According to Laquer the church that he refers to as the site of the graveyard at Stoke Newington, which at the time was a village three miles North East of London, was Old St. Mary's. There is some controversy regarding this claim, however, because while Old St. Mary's was built of brick in the 1820s it had later been covered in cement to give it the appearance of stone.

Both Christopher Wood and Thomas Laquer felt the inspiration for the subject of this painting was Alfred Tennyson's poem In Memoriam, published in 1850 as an elegy for his Cambridge friend Arthur Henry Hallam who had died in 1833 at age twenty-two. Leslie Parris, however, felt the subject "can be related to an older pictorial tradition, inspired by Gray's Elegy, in which a figure is depicted meditating in a churchyard, often leaning on a gravestone. Bowler replaces the twilight of such scenes with sunlight and rational doubts" (130). Thomas Gray's well-known poem "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" had initially been published in 1751 and talks about the death of everyday people who have lived ordinary lives.

When Bowler's painting was shown at the Royal Academy in 1855 it received somewhat mixed reviews despite being praised for its Pre-Raphaelite "truth to nature" qualities. A critic for The Art Journal surprisingly wrote that for some reason the question of doubt should have been raised by a man:

"No. 644, The Doubt, H. A. Bowler, "Can these dry bones live?" This is a most powerful work in many of the most valuable qualities of art. The question is asked by a woman wearing a bonnet and every-day costume, – it should have been asked by a man. The scene is a churchyard, wherein is seen a female figure, leaning on a tombstone, and contemplating the bones which she is thus supposed to apostrophise. Every part of the surface of this canvas is elaborated into the most perfect imitation of natural or artificial objective. The bricks of the church, the overhanging leafy canopy, the tombstones, the grass – indeed, every minute object, is most perfectly represented. All that is wanted to make the picture perfect is the absence of the trunk of the horse-chestnut, which competes with the figure. [182]

W. M. Rossetti in The Spectator also gave a very misogynistic interpretation of the painting: "The Doubt – "Can these dry bones live?" by Mr. Bowler, is a church-yard scene, every detail of which is excellently painted, with a good effect of light transparent through the chestnut-leaves; but, unfortunately, the lady who leans upon the headstone is a poor unmeaning creature, who might as well be going on a morning-call as questioning Eternity about dry bones" (575).

Bibliography

Bingham, David. "The London Dead. Stories from our cemeteries, crypts and churchyards." 8 March 2016. http://thelondondead.blogspot.com/2016/03/secret-portuguesejews-floating-coffins.html

The Doubt: "Can These Dry Bones Live?". Art UK. Web. 17 July 2024.

Gilmartin, Sophie. Ancestry and Narrative in Nineteenth-Century British Literature: Blood Relations from Edgeworth to Hardy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Laquer, Thomas W. The Work of the Dead: A Cultural History of Mortal Remains. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015. 137-140.

Parris, Leslie. The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Tate Gallery Publications/Penguin Books, 1984. Cat. 65, 130-31.

Rossetti, William Michael. "The Royal Academy Exhibition: Domestic Pictures." The Spectator XXVIII (2 June 1855): 575.

"The Royal Academy." The Art Journal New series I (1 June 1855): 169-84.

Wood, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. Aventel, New Jersey: Crescent Books, 1981. 68-69.

Created 23 July 2024