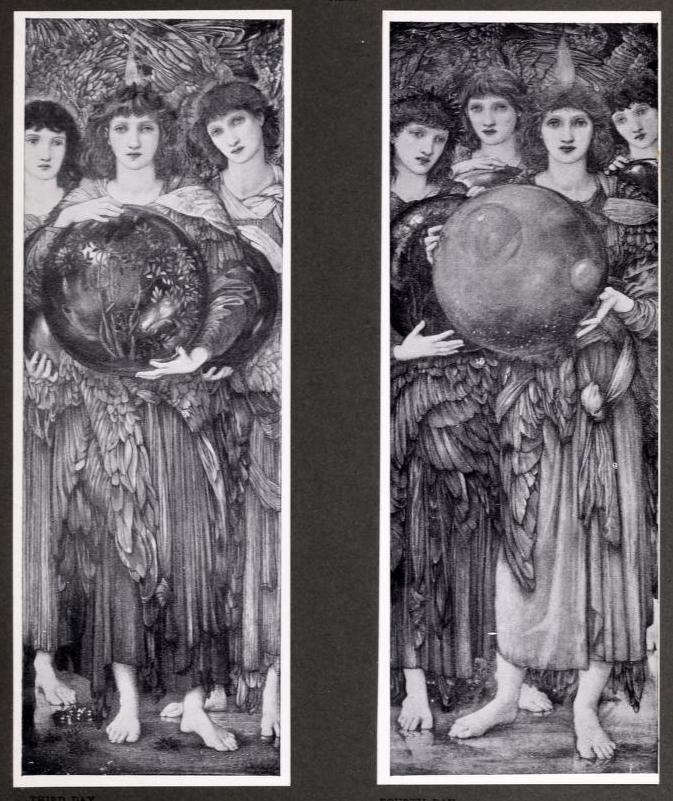

The Days of Creation by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt ARA (1833-1898). 1870-1876. Medium: watercolor, gouache, shell gold, and platinum paint on linen-covered panel prepared with zinc white ground. Dimensions: 102.2 x 35.5 cm (40 1/4 x 14 in.). Burne-Jones made it clear that each picture was only to be viewed in the context of the rest, and in its frame: on the back of the first "day," in black ink or paint, he wrote: "This picture is not complete by / itself, but is No 1 of a series of / six water color [sic] pictures representing / the Days of Creation, which are / placed in a frame designed by / the Painter, from which he / desires they may not be removed. / E BURNE-JONES / LONDON. 1876 / designed 1870 / painted 1875-6" (the materials, size, and inscription are all given on the Harvard Art Museums website). Above, we see the works photographed in three sets of two, unfortunately not in the frame, by Frederick Hollyer (Source: Bell, plates XX-XXII). Click on each set to enlarge it.

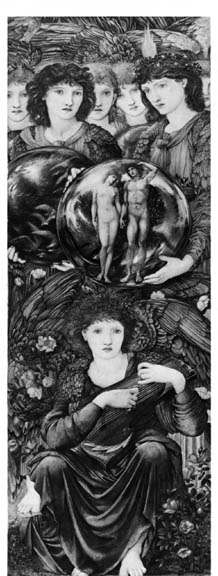

A closer view of the sixth day.

Although comprised of watercolours rather than oil-paintings, this set is one of Burne-Jones's sequences. His idea here was to present the greatest chronological sequence of all, as represented in the opening chapter of Genesis, by showing richly feathered feminine-looking angels, the foremost one of which, in all the canvases except the last, holds a globe indicating what took place on that day. In the last panel, showing the creation of Adam and Eve, one angel is seated in the foreground — an interesting reflection on the importance of Eve's arrival on the scene. Amid an abundance of flowers (instead of bare earth, or, as in the previous one, apparently on the shore), she is playing a stringed instrument, probably a psaltery. In this way she fills the traditional role of a musician angel giving praise to the Creator, an apt conclusion to the sequence. It has all been very carefully devised.

The writer Baronne Madeleine Deslandes, who herself holds a crystal ball in Burne-Jones's portrait of her, interpreted the globes as "symbols of the immeasurable distress of creation" (qtd. in Gere 166). But, if so, the dynamism is contained. Rather, there is an emphasis on calm, and a decorative effect: "For [Burne-Jones] the paramount good of a work of art lay in its beauty and in its broad, universal meaning — to which drama and emotion, beyond a dreamy melancholy, were inimical" (Warner 375). This would be especially important when he decided to prepare the design for an ecclesiastical purpose and setting.

The idea of utilising this kind of composition in a house of worship might already have been somewhere in the back of the artist's mind. Lionel Lambourne makes an interesting link between Burne-Jones's increasing involvement in stained glass design, and his longer and thinner paintings (454). These six narrow panels might either have been inspired by, or have inspired, his decorative work in churches.

Image acquisition, text and formatting by Jacqueline Banerjee. You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [In a much earlier version of this page, George Landow provided the last image, and thanked Chris White for alerting us to a problem with it.]

Related Material

- Ceramic version in Llandaff Cathedral

- The Creation Stories of Genesis

- Astrologia (drawing of another young woman with a crystal ball)

Bibliography

Bell, Malcolm. Sir Edward Burne-Jones. London: George Newnes, 1907. Internet Archive. Contributed by the Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. Web. 2 October 2019.

"The Days of Creation." Harvard Art Museums. Web. 2 October 2019.

Gere, Charlotte. "Portraits." Edward Burne-Jones. Ed. Alison Smith. London: Tate Publishing, 2018. 147-167. [Review]

Lambourne, Lionel. Victorian Painting. London and New York: Phaidon, 1999.

Newman, John. The Buildings of Wales: Glamorgan. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004.

Warner, Malcolm. "161-165. The Days of Creation." A Private Passion: 19th-Century Paintings and Drawings from the Grenville L. Winthrop Collection, Harvard University. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale University Press, 2003. 375-78.

Last modified 12 June 2020