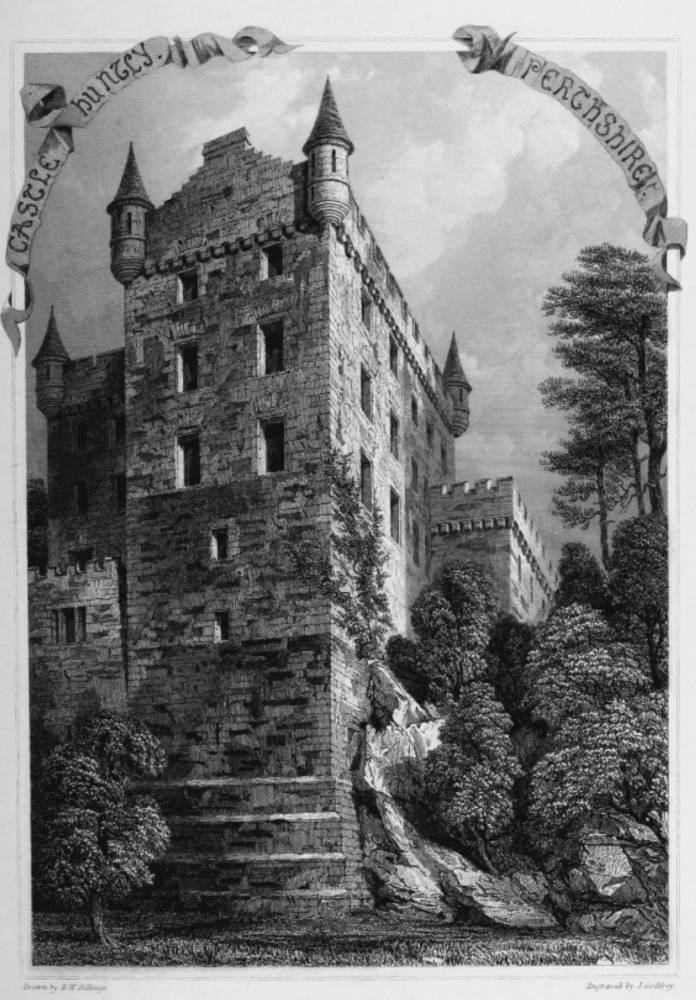

Castle Huntly. Perthsire drawn by Robert William Billings (1814-1874) and engraved by J. Godfrey. Source: The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland (1852). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Commentary by the Artist

From a line a short distance heyond Dundee, the Carse of Gowrie stretches for many miles westward — the Firth of Tay edging it on the south, a line of hills on the north — until it narrows in to a mere valley among the rocky eminences surrounding Perth. It is not quite a dead level, for some slight elevations here and there slope upwards from the flat clay surface, generally receiving the name of inches or islands — a circumstance supposed to show that, even within the age when they obtained their names, a portion of the water which at one time must have made the carse a wide sea lake still remained. But far above all other elevations, almost in the very centre of the district, rises an abrupt rock, formerly washed by the surroundmg waters, on which stands the strong square tower of Huntly or Castle Lyon. From all parts of the surrounding level it has a fine effect. Viewed near at hand, the abrupt rock, and the masonry starting flush with its rugged edge, present one great, gloomy, impending mass, where the boundaries between the natural and artificial portion of the surface are scarcely perceptible; — from a distance, the miniature turrets and embrasures may be seen rising out of the plain, and standing clear, though minute, agaiust the sky. From the roof is seen the firth, with its vessels, and the varied surface of the carse: here, narrow stripes of sand-edged land, stretching into the water, clothed with trees; there, long stretches of cultivated ground, on which, for miles on end, stand curious old orchards of apple-trees, broad, ancient, and moss-grown, like forests of dwarf oak. Such is the scene beneath the eye; but on the boundary of the horizon, especially towards the north and west, rise ranges of mountains, one above another, capped by the distant Grampians.

The perpendicular part of the rock is towards the south-west; it slopes gradually towards the east, where the more modern parts of the mansion are approached by an elevation, formerly bisected by a moat. In the surrounding grounds there are some venerable trees, and a few remains of old walls and decorations. The most ancient part of the castle is the simple Scottish square tower, so frequently erected from the beginning of the fourteenth to the middle of the sixteenth century. In the present instance it is conspicuous in its great proportions and massive strength — the walls ranging from ten to fifteen feet in thickness. The vaults towards the west are partly hollowed out of the living rock. The author of the Old Statistical Account of the parish, describing the edifice before it was partly modernised, says —

Opposite to the southernmost vault, the rock projects a little farther to the westward, and is lower than the rest, upon which the pit or prison was built, also fourteen feet thick walls, and a narrow slit of a window; no passage to the pit but by a trap-door, and over it a square apartment of twenty feet high, arched at top, with a window of four feet square, and thirty-eight feet from the ground, which is supposed to have been the guard-room, the only door of which is arched; and there was not the least vestige of any other way to get access to the castle, even for one man at a time, but over the shelving rock on the south-west, and close by the two windows in the other two arched apartments, one of which is exactly ripon the door, calculated, as it would appear, for the use of spears or other offensive weapons to prevent the entrance of an enemy. [XIX, 476]

This east front of the castle now presents a pile of modem buildings, not in any early Scottish style of architecture, but in that pseudo-baronial, fashionable about fifty years ago.

The castle and its territory anciently belonged to the family of Gray, who still hold considerable possessions on the border of the Tay westwards. We are told of Andrew, second Lord Gray, who was one of the hostages in England for King James I., that "he was appointed master of the household to King James II., from whom he obtained a license to build a castle on any of his lands he thought proper, dated 26th August 1452; and he, in consequence, erected the beautiful castle of Huntly, long the principal residence of his family" (Douglas's Peerage, I, 667). The writer of the Old Statistical Account says — "It is said that, having married a daughter of the Earl of Huntly, he named his castle in honour of his lady but this tradition is disproved by the circumstance that a marriage-contract shows him to have been, on 31st August 1418, married to Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Sir John Wemyss of Rivers, who survived him. When subsequently it became one of the strongholds of the powerful family of Lyon, Earls of Strathmore, the owners also of the more famous castle of Glammis, it received the name of Castle Lyon. In the New Statistical Account — where, though no authority is quoted, the history of the change of name and ownership has an appearance of accuracy — it is said that "the castle, with the fine estate belonging to it, was sold to the Earl of Strathmore in 1615; but it did not become Castle Lyon till 1672, when, in virtue of a charter obtained from Charles II., the barony of Longforgan was erected into a lordship, to be called the lordship of Lyon, a name which it retained till 1777, when it was purchased by Mr Paterson, who, having married a daughter of John Lord Gray, the descendant of the founder, revived its original name of Castle Huntly. It is now the property of his grandson George Paterson, Esq." There are few historical events connected with this fortalice. It was visited by the unfortunate son of James II of Britain, when he showed himself for a short time to the rebel army of 1715 — a circumstance which would hardly have been preserved and so often mentioned, by the historians of that outbreak, but for the scanty train ot events connected with the personal history of the individual on whose account it was undertaken.

R. W. B.

[These images may be used without permission for any scholarly or educational purpose without prior permission as long as you credit the Hathitrust Digital Archive and the University of California library and link to the the Victorian Web in a web document or cite it in a print one — George P. Landow ]

Bibliography

The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland illustrated by Robert William Billings, architect, in four volumes.. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Son, 1852. Hathitrust Digital Archive version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 10 October 2018.

Last modified 15 October 2018