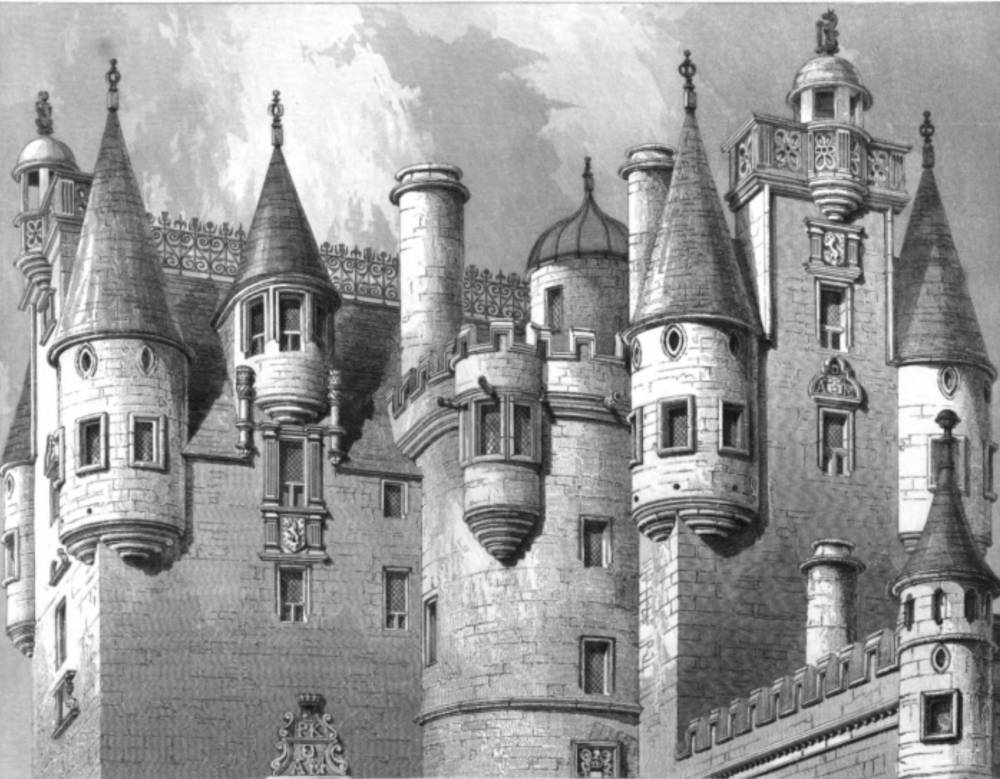

Glammis Castle drawn by Robert William Billings (1814-1874) and engraved by J. H. Le Keux. Source: Edinburgh (1852). [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Commentary by the Artist

Surrounded by dusky woods, and approached by long avenues passing through their shade, this vast pile rears its tall gaunt form, crested with multitudinous cone-topped turrets, abrupt roofs, stacks of chimneys, and railed platforms. Though it has been shorn of many of its ancient glories, and the buildings which crouch beneath the great tower are manifestly modern, no other castle in Scotland probably stands in this day so characteristic a type of feudal pomp and power. It by no means detracts from the solemn grandeur of this edifice and its overawing induence,that it conveys no distinct impression of any particular age, but appears to have grown, as it were, through the various periods of Scottish baronial architecture. The dark, low, round-roofed vaults below-the prodigioust thick masonry of the walls, and the narrow orifices-speak of the earliest age of castellated masonry, and indeed exhibit manifest indications of the Norman period. The upper apartments appear to belong to the fifteenth or sixteenth century; and the rich clusters of turrets, with the round tower staircase; are evidently the productions of that French architectural school, which first appeared in Scotland early in the seventeenth century.

The edifice is in fine preservation, down to its most minute details; and though in a great measure dismantled, a few relics of the possessions of its lordly owners retain considerable interest. In the great hall-the beautiful pargeted roof of which is depicted in the accompanying plate-there are several pictures-some of them of no small value. They have lately been restored, and their frames have been gilt, so that their glossy exhibition-room-like freshness is in contrast with the grim antiquity of the surrounding objects. Some specimens of old armour-chiefly Oriental, and not of much interest or value-are shown to visitors. More worthy of observation is a clothes-chest containing some court-dresses of the seventeenth century, still glittering in not entirely obliterated finery, among which is preserved the motley raiment of the family fool, whose licensed jests had lightened the heavy pressure of unoccupied time in the long evenings, before Charles I. was beheaded or Cromwell had become great. Not the least interesting among the interior features is an old painted and pannelled chapel, in pristine preservation, which, though forming one apartment of a great building of many storeys, curiously reminds one of travelling in Catholic countries abroad, and of “the chapel far removed that lurks by lonely ways.” But not the least source of enjoyment to the visitor of Glammis will be, if the day be fine, to look around him from the railed platform, on the top of the tower, to the wide valley of Strathmorc, full of luxuriant woods and rich cultivated domains.

Drawn by Robert William Billings and engraved by J. H. Le Keux. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

This castle claims traditionally a high antiquity. Fordun and the other chroniclers tell us, that in its neighbourhood Malcolm II. was attacked and mortally wounded in 1034, and that his assassins perished in attempting to cross the neighbouring loch of Forfar, then imperfectly frozen over. Pinkerton, who was never content with doubting the truth of any historical statement, but who had always some directly opposite narrative to prove, tells us that “Malcolm II. died a natural death at Glammis,” and that “the fables of Fordun and his followers, concerning Maleohn’s dying in a conspiracy, have not a shadow of foundation” (Inquiry into the History of Scotland, ii. 192). On the other hand, tradition has so far realised and domesticated the assassination, as to show the chamber of the castle in which it occurred; while, to put all scepticism to shame, it points out the indubitable four-posted bed in which the deed was perpetrated. This form of the legend is evidently an adaptation of the dramatic version of the murder of Duncan by Macbeth; and indeed the chamber has been not unfrequently shown as the scene of this great tragedy, for which its adjuncts make certainly a very appropriate stage. The earliest authentic proprietary notices of Glammis show it to have been a thanedom, and its lands regal domains. On the 8th of March 1372, King Robert II.,by charter, granted to Sir John Lyon “our lands of the Thainage of Glammis” (Terras nostras Thanagii de Glamuyss. Reg. Mag. Sig, page 90). The family of Lyon was ennobled as Lord Glammis in 1445, as Earl of Kinghom in 1606, as Earl of Strathmore in 1672.1' The reader of Scottish history will have made himself familiar with many events in which the lords of this fortalice took part. It is noticed for the last time in history in connexion with the rebellion of 1715, when the Chevalier lodged for some time in the castle, and there received his principal followers. luxuriant woods and rich cultivated domains.

It is traditionally stated, that the later portion of the edifice is the work of Inigo Jones; but there is no evidence of the truth of the statement. Considerable additions were undoubtedly made to the buildings by Earl Patrick, who died on 15th May 1695 (Douglas, II, 566).

During the eighteenth century, and before its approaches were modernised, Glammis frequently 'elicited expressions of strong admiration from tourists. “It is,” says the author of the tour attributed to De Foe, “one of the finest old built palaces in Scotland, and by far the largest. When you see it at a distance, it is a pile of turrets and lofty buildings, spires and towers — some plain, others shining with gilded tops, that it looks not like a town, but a city” (Tour through Great Britain, iv. 196.). Gray the poet, in a letter to Wharton in the autumn of 1765, concludes a minute description of the castle and the grounds, with the general remark that “the house, from the height of it, the greatness of its mass, the many towers a-top, the spread of its wings, has really a very singular and striking appearance like nothing I ever saw” (Works, IV, 53-54). Scott bitterly lamented the subsequent landscape-gardening operations, which, sweeping down all the exterior defences, left the clustered tower standing alone, in the middle of a park, unprotected, like a modern peaceful mansion. “The huge old tower of Glammis, ‘whose birth tradition notes not,’ once showed its lordly head above seven circles (if I remember aright) of defensive boundaries, through which the friendly guest was admitted, and at each of which a suspicious person was unquestionably put to his answer. A disciple of Kent had the cruelty to render this splendid old mansion (the more modern part of which was the work of Inigo Jones) more parkish, as he was pleased to call it: to raze all those exterior defences, and to bring his mean and paltry gravel-walk up to the very door from which, deluded by the name, we might have imagined Lady Macbeth (with the form and features of Siddons) issuing forth to receive King Duncan” (“Essay on Landscape Gardening,” Life, I, 294). Scott spent a night in Glammis castle in 1793, and he concludes a curious account of his sensations on the occasion, by saying — “In spite of the truth of history, the whole night-scene in Macbeth’s castle rushed at once upon me, and struck my mind more forcibly than even when I have seen its terrors represented by John Kemble and his inimitable sister” (Letters on Demonology and Witchcraft, 398. Life, i. 296.).

R. W. B.

[These images may be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose without prior permission as long as you credit the Hathitrust Digital Archive and the University of California library and link to the the Victorian Web in a web document or cite it in a print one — George P. Landow ]

Bibliography

The Baronial and Ecclesiastical Antiquities of Scotland illustrated by Robert William Billings, architect, in four volumes.. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Son, 1852. Hathitrust Digital Archive version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 10 October 2018.

Last modified 11 October 2018