In my personal copy from which I have scanned the following essay on Reynolds, the earliest of numerous copyright dates is 1886, but Van Dyke’s preface is dated 1901. In transcribing the following essay on Hogarth, I left the author’s placing titles of books and paintings between quotation marks and added the books’s original engravings. — George P. Landow .

F family anecdote is to pass current for history, it would seem that all the famous painters were infant prodigies with the pencil. They were all of them idle school-boys who spoiled text-books with marginal drawings, charcoaled newly whitewashed walls, and outlined various animals on stone, wood, or any smooth surface that came to hand. Reynolds was no exception to the rule. He, too, defaced wall and book, and once, having backed up a Latin exercise with graphic delineation, his unsympathetic father recorded his opinion of it thus: “This was drawn by Joshua in school out of pure idleness.” Of course after Joshua became famous his father was pleased to remember these supposed signs of incipient genius; and had he tried hard he might have remembered signs of the same sort shown by his ten other children, who did not become famous. All children use the pencil, make rhymes, and fight mimic battles “ out of pure idleness,” but these commonplace facts of child life are afterward remembered only of the great painters, poets, and generals. Reynolds’s figures, like Giotto’s sheep, would seem to prove the boy in the artist rather than the artist in the boy.

There was nothing remarkable about Sir Joshua’s childhood. He was born at Plympton, July 16, 1723, and probably received a better education at the hands of his clerical rather than most boys of his time. There was some talk at first of his studying medicine, but matters shaped themselves otherwise. The youth wished to be a painter, and at eighteen he was sent up to London to study painting under Hudson, with whom he remained for two years, learning something about the way the old masters drew, and painting some portraits on his own account Then he suddenly left London, returning to Devonshire, where he passed some time, to no profit, as he afterward seemed to think. Later he, with two sisters, took a house at Plymouth, and in 1746 he was again in London, painting portraits for a living, and trying to get on in the world.

He was possessed of social qualities and soon made friends. Fortunately enough for him, he won the good opinion of Captain Keppel, who invited the young painter to go with him tee the Mediterranean on his ship the Centurion. Reynolds accepted, voyaging to Gibraltar and Algiers, and painting portraits whenever the opportunity was afforded. In 1749 he found himself in Leghorn, and soon after in Rome, where for two years he gave himself up to a study of the Italians, chiefly Michelangelo and Raphael. It was while studying in the Vatican that he caught cold, became deaf, and was compelled to use an ear-trumpet for the rest of his life. He spent some months in the year 1752 studying the pictures at Florence, Parma, and Venice, shortly afterward returning by Paris to London, where he at once set up a studio in St. Martin’s Lane and began portrait-painting as a profession.

At first his style was not applauded by the painters, and Ellis told him he did not paint in the least like Sir Godfrey Kneller. His method was somewhat novel, but he saw to it that the innovation should not be too startling for public approval. He met with encouragement almost from the start. The Duke of Devonshire and his friend Keppel gave him commissions; others followed, and the painter was soon able to move to Great Newport Street and to raise his prices. Something of a courtier, and always a gentleman, Reynolds had little trouble in making his way with the great people of the day, noble and otherwise. It was not long before he knew almost every one of note. Johnson, Burke, Goldsmith, Garrick, Wilkes, became his dining companions at “The Club" and elsewhere; and their table-talk was for many years the town talk. In this brilliant circle Reynolds himself cut no inconsiderable figure, for at thirty he had achieved a fame that never left him.

The larger his acquaintance, the greater seemed his success as a portrait-painter. He had so many orders that assistants had to be called in. Again he moved to more spacious quarters in Leicester Square, and again he raised his prices. He was growing rich, and advertised the fact by setting up a coach. In 1768 came the founding of the Royal Academy. Reynolds was made its first president, and the king knighted him. Five years later Oxford gave him the degree of D.C.L., and he was appointed painter to the king. Honors were falling fast upon him, but his head was not turned by them, and for all that he was the first portrait-painter of his time, he never relaxed his industry. He believed firmly in the efficacy of labor, and was never idle. At his apogee he was painting a hundred and fifty portraits a year. In 1781, and again in 1783, he made short trips in Belgium and Holland, studying and making notes of the pictures there; but as soon as he returned to London he took up the brush again like a young aspirant, trying with each new picture to rise above himself.

At sixty-six, in the full flush of his power, his labors were suddenly stopped. While painting, one day, the sight of his left eye grew blurred. He put down the brush, and never took it up again. In a few weeks he was blind in one eye and the other was affected. Some quarrel or misunderstanding arose in the Royal Academy, and Sir Joshua resigned its presidency, then resumed it again at the king’s request, but finally gave it up in 1790, after twenty-one years of rule. He never married, his family were dead or scattered, and with his occupation gone the painter failed rapidly. He died February 23, 1792; and, after a funeral which all London attended, he was buried beside Sir Christopher Wren in St. Paul’s Cathedral. He left behind him a great reputation, a vast number of pictures (chiefly portraits), his “ Academy Discourses” (so good in style that at one time Johnson was supposed to have written them), and sixty thousand pounds in money.

The manner in which Sir Joshua ordered his personal life is indicative of the spirit that influenced his art There was nothing erratic, venturesome, or impulsive about either. It is difficult to believe that the man at any time, either in life or in art, possessed much fire, passion, or romance. He was too calm for either love or hatred, too conservative for brilliancy, too philosophical for enthusiasm. In art he placed less reliance upon inspiration than upon intelligent knowledge, believed the gospel of genius to be work, and thought originality a new way of saying old truths. Stich ideas as these form the chief counts in his discourses to the students of the Royal Academy. “ Excellence is granted to no man but as the reward of labor.” And again: “ Have no dependence on your own genius; if you have great talents, industry will improve them; if you have but moderate abilities, industry will supply their deficiency.” His three stages of an art education were, first, learning the grammar of art; secondly, laying in a stock of ideas from the old masters; thirdly, independent action, but in moderation.

And Sir Joshua usually practised what he preached. He hugged conservatism, held fast to the traditions, and tried to keep his genius in abeyance to rule and method. That he had genius cannot be denied; but in his own mind he confounded it with energy, and thought himself successful through work. He had slaved over execution, he had studied the art of the past, and with much labor had made other people’s excellences his own. Naturally he thought work and education accounted for his success Undoubtedly they were a great aid to him. The stock of ideas from the old masters helped him; his borrowings from others and his powers of assimilation helped him; but many painters have possessed these qualities and yet never attained high rank. Success as the result of such accomplishments would explain genius out of existence. Sir Joshua’s fame does not rest upon them. There was nothing in his technical mastery, wherever or however he got it, upon which to base a great reputation. His technique was the weakest feature of his art.

Sir Joshua’s “borrowings” have been much talked about It is true he could absorb excellences in others as silently and as gracefully as Raphael, and leave less of a trail behind; but it should be borne in mind that the education of the painter in eighteenth-century England was largely a matter of “borrowings.” All the students of the time copied Raphael, Correggio, and Guido, and such a thing as a thorough academic training under a skilled master was not to be obtained. Indeed, it is not pushing the facts too hard to say that there was not a perfect craftsman in the school. Deficiency in training was made up for by taking hints from the old masters and by practising observation. Reynolds had greater chances than the others, and he improved them. " I know no man who has passed through life with more observation than Sir Joshua Reynolds," said Johnson.

What he observed as a pupil under Hudson we have slight means of knowing. Hudson was hard and dry in method, but, like all the painters of the time, he reverenced Van Dyck. And the Van Dyck doctrine of “painting noble men nobler still” Reynolds accepted in measure. He told his Academy students that it was the duty of the portrait-painter “to aim at discovering the perfections only of those whom he is to represent”—a maxim he himself did not always follow, though doubtless he believed in it And of course he believed in the Italians, for they were the fashion of the day. In Rome, like many another painter, he was at first disappointed in Raphael, but afterward grew very fond of his work, and in consequence declared that taste in art was not natural, but acquired; not on the surface, but underneath. Michelangelo impressed him instantly and lastingly. He talked about him all his life, held him up as a model to his students, but he himself did not follow him, except in the oft-cited case of the “Mrs. Siddons as the Tragic Muse.” He had nothing of Michelangelo’s line, form, or spirit, nothing of Raphael’s style or composition.

He talked less about Correggio and the Venetians, yet here he helped himself more freely. It is not difficult to put a hand on the supposed Correggio that furnished him with the model for his coy children. Certainly the sidelong glance, the wavy hair, the small chin, the arch bend of the head, came from Parma. In Venice he studied Titian’s light and shade, and copied it in parts, as he had copied Raphael’s figures at Rome. Paolo Veronese also had an influence on his color, though Sir Joshua talked little about him. Nor did he discourse much on Guido and Guercino, yet one feels that his nymphs and Venuses were drawn from those sources — affectation and all. Besides these painters, he had the contemporary admiration for the Carracci: the eclecticism of Bologna was in both his theory and his art, and he even recommended Lodovico Carracci as a model in painting.

Portrait of Lord Heathfield . Engraved by Tomothy Cole.

But notwithstanding Sir Joshua’s admiration for the Bolognese, he was a very good judge of painting. He had not studied the art of Europe without profit In the main he was right about Michelangelo, right in thinking Velasquez’s "Innocent X” one of the greatest portraits in the world, right in thinking that Jan Steen’s style "might become even the design of Raphael.” He knew very well how a thing should be done, but he did not always know how to do it. "Not having the advantage of an early academical education, I never had the facility of drawing the naked figure which an artist ought to have.” No, he had not. His drawing of the figure was tentative, hesitating, uncertain, hardly ever complete or wholly satisfactory. Hands he sometimes drew easily, and faces he understood better than anything else — not always drawing them truly, but painting them very cleverly with the brush, and giving the fleshy texture with much force. If one compares the “Lord Heathfield,” the “Dr. Johnson,” or any other portrait by Reynolds, with the “Cornelius van der Geest” portrait attributed to Van Dyck in the National Gallery, the difference between the tentative and the absolute will be immediately apparent The drawing of the mouth, nose, eyes, cheeks, and forehead in the “Van der Geest” is positive, done easily, surely, unostentatiously; that of the “Heathfield” is rambling, questioning, groping. Doubtless much of Sir Joshua’s unevenness was due to frequent emendation,— his wish to better each part,— but that in itself is proof of uncertainty. Still, though never having the positiveness of a Raphael, his drawing had a picturesque quality about it that rather helped than hurt his purpose. His art was not academic and therefore did not need severity or absolute accuracy.

Lady Cockburn and Family. Engraved by Tomothy Cole.

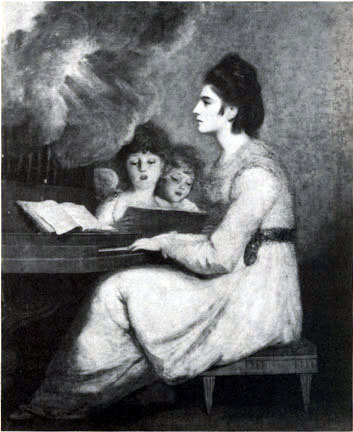

Sir Joshua’s success with composition was not greater than with drawing. He could pose a portrait-figure happily enough, but his so-called “historical” pictures were deficient in invention and imagination. He could not see nymphs and Venuses and classic groups except as some old master had seen them before him; and because he saw portrait-subjects, and did not see figure-subjects, is one reason why he succeeded with the former and virtually failed with the latter. At times, however, he was very clever in composing a family group, as the “Lady Cockburn and Children” will exemplify. The manner in which he has woven and intertwined the lines of the figures with the drapery, knit the whole group together in form and color, and made a complete ensemble, is worthy of all praise.

Color he experimented with all his life. He believed that the secret of it was known to the Venetians, but lost. “There is not a man on earth who has the least notion of coloring; we all have it equally to seek for and find out, as at present it is totally lost to the art.” Sir Joshua sought for it with all pigments, mediums, and methods, and with some unfortunate results. In his experimental canvases painted during his early and middle periods he at times used fugitive blues, lakes, carmines, orpiments, mixing them with oil, wax, varnish — almost anything that would produce a desired effect But the effect was often transient; the colors fled the canvas, the lights bleached, the shadows darkened, and as a result many of his otherwise fine portraits are to-day pallid and cold. In fact, Sir Joshua’s fading color was something of a town jest, and the girding Walpole suggested that his pictures should be paid for in annuities, to last as long as the pictures lasted.

The painter felt badly enough about his fleeing colors, and he so mended his manner that many of his later canvases gave no cause for criticism on that score. Some of them are to-day in excellent preservation. Moreover, they are fuller and richer than his earlier works. In color, as in light, he finally returned to Rubens. The “ Lady Cockburn and Children ” shows how ornate he could be and still keep within the bounds of good taste. Sir Joshua was not quite correct in saying no man living had any notion of color. He himself had a shrewd knowledge of it His dictum about the use of warm and cold colors argues nothing whatever. He produced fine pieces of color on more than one occasion, not by virtue of any law or rediscovered secret, but because he had the color-instinct. Were he as much of a draftsman as a colorist, no one would be able to find many holes in his armor. As a brushman he was not remarkable, though effective, and occasionally he struck off the ornaments of a dress or the flow and fall of hair with the positiveness of a Velasquez. But he was too careful, as a rule, to trust the quick stroke. More often he thumbed and kneaded, amending with “just another touch,” until finally the surface looked labored—“bready,” as they say in the studios. Freedom of handling, in the Frans Hals sense, was not known to any member of the school. Romney and Raeburn and Lawrence were dashing enough, to be sure; but sometimes they struck wide of the mark. They never had the certain brush of a Hals.

It might be thought from his art principles that Sir Joshua would have evolved a style, a manner somewhat like Raphael, the Carracci, or even the eclectic Mengs; but he never did. He talked much of things established, but took good care not to have them too firmly established with him. Every picture he painted was, in measure, different from its predecessor. He was changing and improving with each effort, always striving for some new excellence, always ready to adopt a new suggestion. He might lack in early training, but he missed no opportunity in later study. Painstaking, industrious, persevering in the acquisition of knowledge, it is not remarkable that he finally became a painter of unusual culture. He never was quite spontaneous, never quite original in the sense of inventing a method wholly his own, never quite perfect in craftsmanship. If examined closely, many of his works will be found wanting. Take, for instance, the portrait of “Lady Elizabeth Foster.” It is not drawn, modeled, or painted. The features want articulation, the figure lacks solidity and substance, the color is chilly, the whole picture, even regarded as a sketch, lacks force. It will not stand by its technique alone. Yet, in spite of its sins of omission and commission, the portrait is most engaging, full of charm, full of loveliness. What is it about the work — about all of Sir Joshua’s portraiture — that appeals to us so strongly ?

It has been said that a portrait-painter puts no more in a head than there is in his own, which is equivalent to saying that every artist paints his own point of view. This was true of Sir Joshua. With all his eclecticism and his absorptions from hither and yon, he never forsook his own individual way of seeing things. If there was any struggle between the portrait-model before him and the established Italian or Dutch method of doing a portrait, it generally resulted in his trusting his own eyes. In the canvas the painter outbalanced academic rule, and to this day every one of his portraits bears the individual stamp and seal of Sir Joshua Reynolds.

Now Sir Joshua’s view was peculiarly attractive. He was conversant with the best side of social England in the eighteenth century, and was, moreover, a man of good breeding, refinement, and sensitive perceptions. Naturally he was in sympathy with everything well-bred and refined in his sitter. He saw that phase of character acutely, and selected it as best suited for his purpose. If there was anything manly about a man, feminine about a woman, or childlike about a child, he noticed it at once. And these were the qualities upon which he concentrated his strength. He appealed frankly and boldly to the taste for dignity, charm, winsomeness, loveliness, in the personal presence, and the appeal was not in vain — is not in vain to-day. The world has never been so deeply in love with the beauty of the ugly that it could not enjoy the beauty of the comely and the noble. Nor is there anything of idealism or flattery in this view. Pleasing qualities are just as real as repulsive ones. The painter always selects what he shall emphasize. Some there be who select the greasy qualities of Joan keeling the pot; but Sir Joshua preferred painting the most elevated and agreeable qualities of his sitters.

Left: Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Right: The Honorable Mrs. Graham (1704-1782). Both engraved by Tomothy Cole. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

This was particularly true of his women. The eternal womanly he saw in every woman — saw it in Kitty Fisher and Nelly O’Brien as well as in the Duchess of Devonshire and Lady Powis. Besides this, he saw in some haughtiness, loftiness, distinction; in others mildness, maternal feeling, sadness; in others again, gaiety, coquetry, gracefulness. How shrewd he was in his observation of the look, the pose, the smile that make women captivating! How sensitive he was to the young girl’s modest glance, the coquette’s sly roguery, the lady’s frank demeanor! The witchery of women, the fascination of the sex, the nameless something that leads on to love, he knew by heart, though no wife taught him. And he knew with just what happy incident to portray them, though no old master gave him the hint. What, for instance, could be more winning than the “Viscountess Crosbie” coming out from behind a tree, a smile upon her face, and her hand outstretched in greeting! One’s first exclamation is: “You charming creature! What a pity you are dead!” The graceful step and expectant look of "Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire,” as she comes down the terrace steps, the woman still in the duchess; the loveliness of “Mrs. Bradyll" and the “Ladies Waldegrave”; the coy impishness of “Mrs. Abington”; the questioning glance of “ Perdita Robinson”; the demureness of “Kitty Fisher” — how very attractive they all are!

Mrs. Sheridan as Saint Cecilia. 1790. Engraved by Timothy Cole. Oil on canvas. Waddeson Manor, Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire.

And how interested we become in the subject! You cannot be so enthusiastic over the women of Velasquez, Rubens, or Holbein. Even the Venetian women of Titian, perfect types of beauty as they are, provoke only a mild curiosity as to their personality. We rather overlook the painted in the painter. But Sir Joshua’s people attract us, and the subject — the much-despised subject of modern art — has weight in this English portraiture. The painter intended that it should have weight — intended that people should know and feel the charm of the sitter. It is matter of history that he had the most noble and beautiful women of England for sitters. They look it An air of distinction and refinement hangs about them as easily as a cloak. Women of less beauty and less nobility sat to him, but their pictures were never his great successes. He preferred the handsome woman, and it was a part of his selective sense that led him to paint her so often. He did not and could not entirely sympathize with the plain or the homely. Sir Joshua was fortunate, then, in having attractive subjects for his art. He was fortunate again in having an attractive point of view. With such winning cards, it is easy to see that he had two points out of three in the game of portraiture. Had he been as successful in the third point, technique, as in the other two, he would have ranked as a portrait-painter with Van Dyck.

Duchess of Devonshire and Child. Engraved by Tomothy Cole.

His children, when done directly from life, were almost as successful as his women. There is some mannerism about the majority of them,— a reminiscence of the way Correggio painted children, — but they are no less childlike and graceful. The fancy for round eyes, a wide smile, and a sharp-pointed chin with a consequent mouselike expression of face prevails. We see it in the charming piece of the “Lady Gertrude Fitzpatrick ” standing on a hilltop, ip the “ Muscipula,” the “ Robinetta,” the “ Strawberry Girl," the “ Cupid as a Link-boy.” Presumably Sir Joshua employed this peculiar type to give the shy, frightened, or nervous character of children, and if so he certainly succeeded; but he is more pleasing when he gives the unconscious, self-absorbed character, as in the richly hued “Little Fortune-teller,” the “ Dead Bird," the " Master Bunbury,” the “Age of Innocence,” or the little “Miss Bowles” with the dog.

He was very successful, too, with portrait-groups of women with children, two of which Mr. Cole has engraved. The children in the group with Lady Cockburn are arranged, composed — posed, in fact; but how well this is done, and how firm is his grasp of the salient truths of childhood! Then, again, what could be more natural, unconscious, vivacious, than the Duchess of Devonshire,— the “Beautiful Duchess,” as she was called,— playing at “hot cockles” with her infant daughter! Both pictures were painted in the painter’s mature period, when he had arrived at the height of his power, and both are excellent. They seize upon the incidental, the momentary, which was discoursed against by Sir Joshua in favor of the general and the permanent; but he himself proved more than once that his rules for the “grand style” were subject to many exceptions. He certainly never produced richer, fuller, nobler, more complete works of art than these two portrait-pieces.

His success with portraits of men was perhaps not so great. Occasionally he did a scholar or a general with great truth and power, but he seemed to have more sympathy with women and children. Every Englishman considers the “Lord Heathfield” a masterpiece, and in its original state it was undoubtedly a strong portrait Unfortunately, one of its owners saw fit to cut it down to match another Reynolds on an opposite panel in his house, thus destroying the placing of the figure on the canvas; and after that it was repainted somewhat. It is still a noble canvas, in spite of bad treatment and shows to-day something of the sturdy manhood of the English officer. The “ Dr. Johnson ” is heavy in touch and drawing, but portrays with much effect the unwieldy frame and the massive features of the irrepressible doctor. Sir Joshua’s portraits of himself, of Gibbon, of Goldsmith, are also good pieces of characterization, beside which the flamboyant “Marquis of Rockingham,” the too heroic “Keppel,” the over-dramatic “Lord Ligonier” will not stand for a moment Whenever Sir Joshua tried to practise his “old master” theory of generalization he left something to be desired. He had not enough imagination to see the abstract like a Titian or a Paolo Veronese; he needed the concrete before his eyes. When the model was on the platform he did not fail to see truly, and even at times powerfully; but whenever he wandered off to do the heroic or the grand he ran to the superficial.

This is peculiarly true of his efforts in historical painting. The figure-piece was his lifelong aspiration, but never his success. The “Death of Dido,” the “Cleopatra,” the “Ugolino”—all the figure-pieces he ever did—would not save a name from the dust of oblivion. He painted half a dozen landscapes, but he never pretended to be a landscape-painter. He used trees, hills, and skies well enough as a background, just as he occasionally painted animals after Van Dyck ; but they were mere accessory objects. We may dismiss them all, for Sir Joshua was a portrait-painter pure and simple. The limitation is not to his discredit. He could not have chosen a loftier field to work in. In the whole realm of painting there is nothing so difficult to produce as a thoroughly satisfactory portrait And Sir Joshua produced more than one of them.

Taking him for all and all, Reynolds must be ranked at the head of the English school. He had not Hogarth’s originality, nor Gainsborough’s delicacy, nor Romney’s spirit nor Lawrence’s skill; but in point of view, taste, intelligence, and breadth of accomplishment he excelled any one of them. Perhaps he had more opportunities than the others, but the manner in which he seized the opportunities showed his ability. Not alone did peer and duchess rank him as a great painter: his brothers of the craft acknowledged his position, and all through the works of his contemporaries and followers we shall find traces of his influence. He was virtually the founder of the school of English portrait-painters. He led the procession, and public opinion for a hundred years has kept him in the lead.

Bibliography

Van Dyke, John C. “Sir Joshua Reynolds.” Old English masters engraved by Timothy Cole. London: Macmillan, 1902.

Last modified 23 April 2021