[All images other than the first one are from the sources specified, rather than the book under review. They can be used without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, provided you cite the photographer/source, and link your document to the Victorian Web or cite it in a print one. Click on the thumbnails for larger images.]

The front cover of Michael Nelson's book shows the right-hand side of Edward Lear's romantic View of Villefranche (pen and ink, and watercolour, 1865); it is particularly appropriate because Lear had given the Queen some drawing lessons in 1846 (Nelson 29).

"On our way down to Villefranche we met Leopold II of Belgium walking. He had arrived in Villefranche harbour on his yacht this morning," wrote Queen Victoria in her journal of 4 April 1898 (qtd. in Nelson 127). That the Queen should just happen to have bumped into a royal relation (Leopold was her first cousin) somewhere between Nice and Monaco seems an amazing coincidence. But it was not. During the late Victorian period, anybody who was anybody might be staying on the Riviera. In fact, Leopold had a house on Cap Ferrat there, not to mention another house for his mistress, one for his father-confessor, and a private zoo. As for the Queen herself, by now she was in her seventy-eighth year and on her eighth visit to the area, staying in Cimiez, just above Nice. For all her dislike of republicanism, she had a great affection for the French Riviera, and had been coming there on and off for sixteen years. Queen Victoria's "French connections" are not often discussed, but they were an important aspect of her life, and indeed of the political and cultural life of her country. Bringing them to the fore now is all part of the twenty-first century revaluation of the queen herself, and of Victorianism in general.

"Her Majesty's Gracious Smile," a visiting card with a photograph by Charles Knight dating from 1887 (Library of Congress Digital Gallery, reproduction no. LC-USZ62-93417), the year of her Golden Jubilee. She had visited Cannes earlier in the year.

Michael Nelson's monograph, introduced by Lord Asa Briggs as President of the Victorian Society, is everything one might expect from a former Reuters head. As well researched as it is readable, it draws on a wide range of primary and secondary sources — from municipal and church archives on the Riviera, to the Royal Archives at Windsor; and from Victorian publications in French and English to recent biographies such as Peter Levi's Edward Lear (1995). After a general introduction, chapters deal with each of the successive visits, with an epilogue discussing the cancelled visit of 1900, along the way yielding fresh entries into the events of these years both in the Queen's own life, and in the political context of the times. Tucked away at the back are twenty-five pages of notes in smaller print, a chronology and an equally useful list of selected dramatis personae. What emerges most powerfully is the queen's unquenched appetite for life, nowhere expressed more vibrantly than in her own journal entries from the Riviera.

First, Nelson's introduction explains the role of the English in popularising the area. The opening up of the coast by the railways, and the royal visits, resulted in a huge influx of new visitors. At the beginning of the 1860s, when Swinburne came out to nearby Menton to recover his health, about 4000 visitors stayed in Nice; by 1879, about three years before the Queen's first visit, it was already between 12,000 and 15,000; by the end of the century, the number was about 100,000 (Nelson 9). The Queen's choice set the seal on the Riviera as an up-market holiday resort rather than simply as a place for a cure or convalescence, and it has never looked back since.

Early Visits

Left to right: (a) The Queen's visit to the Chateau d'Eu in 1843, painted by Eugene-Louis Lami (from the Yorck Project on Wikimedia Commons). (b) The new casino at Monte Carlo, designed by Charles Garnier and opened in 1879 — a favourite haunt of the Prince of Wales. The Queen was not alone in her distaste for it; British doctors too considered it a threat to health. (Photomechanical print, Library of Congress Digital Gallery, reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsc-05953.) (c) A shepherd in an olive grove, answering well to the Queen's description; she noted that the shepherds had no sheepdogs (photomechanical print, Library of Congress Digital Gallery, reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsc-05940).

As Nelson explains in his first chapter, Queen Victoria had already visited France twice before coming to the Riviera, both times with Prince Albert. In 1843 the royal couple had stayed with King Louis-Philippe ay Chateau d'Eu in Normandy, and in 1855 they had visited Paris at the invitation of the Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugenie. Like these previous trips, her first visit to the Riviera was a great success. Chapter II recounts how, in the spring of 1882, the royal party undertook the thirty-hour journey from a foggy Windsor by carriage, train, the Victoria and Albert yacht (for the channel crossing), and by train and carriage again to Menton, where the railway magnate Charles Henfrey had offered her the use of his villa. The Queen, widowed and in her early sixties by now, was accompanied by her youngest daughter, Princess Beatrice. Despite the mosquitoes and the grumpiness of her ailing Scottish servant, John Brown, she had a wonderful time. The fine weather, scenery, gardens and views all delighted her. To Lear's disappointment, she failed to visit his new house (Villa Tennyson) and garden in San Remo, over the border in Italy, but she did visit Monte Carlo, despite her intense disapproval of this far-famed den of iniquity (Nelson tells us that a society was formed in London for its abolition). On her trips into the surrounding countryside, she was much taken with the local shepherds, accurately describing them as "very picturesque looking, wearing knee breeches, sort of white stockings and leggings, and a large black felt hat," adding, "Some are very handsome boys" (qtd. in Nelson 35). She was sad to leave what she called "beloved and beautiful Mentone!" (qtd. in Nelson 36).

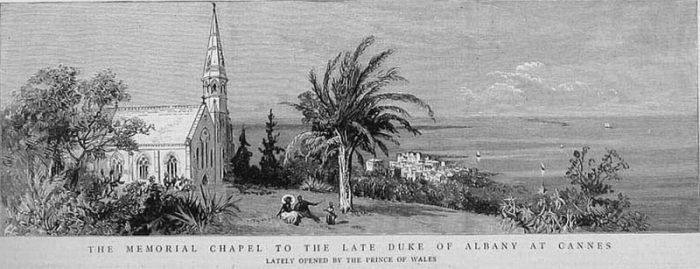

Left: the old harbour at Cannes taken by the present author in 2011, but not so very different from the way it would have looked at the end of the Victorian period. The Queen's youngest son Leopold had been sent to Cannes as a boy, for health reasons, and would die there. Right: picture in The Graphic of St George's Church, Cannes, raised as a memorial to him (26 Feb. 1887, p. 213).

At Menton, the Queen had been joined by her youngest son, Prince Leopold, a haemophiliac who from boyhood had been expected to benefit from the healthy climate on the Riviera. But two years later he died in Cannes, after slipping at the yacht club. The Queen's next visit to France, recorded in Chapter III, was in 1885. She came to see the villa where he died, and the church built in his memory. It was a brief and inevitably unhappy visit. Even the service in the new church, without any uplifting music, left much to be desired. After only a few days the royal party left for Aix-les-Bains in Savoy. But three-quarters of the Queen's time in France, the country which accounted for half her foreign travel, was spent on the Riviera, and in 1891 she was back, staying at medieval Grasse, high in the foothills of the French Alps, overlooking the Bay of Cannes. She had come to see Alice de Rothschild's gardens at the Villa Victoria, but her visit put the whole town on the map: the town council published a commemorative book about it in 1991. Chapter IV deals with various visitors during this stay, including Duleep Singh, the Maharajah of the Punjab, forgiven now for having plotted to get his kingdom back; and with the incidents that punctuated it, like the death by blood-poisoning of the Queen's personal maid. Inevitably, the Queen was much upset by the latter, and threw herself into the funeral arrangements. She never did anything half-heartedly or without that "irresistible sincerity" which Lytton Strachey noted in her long ago (265). Despite some problems, a maid of honour reported in a letter to her mother, after a drive to the village of Pont du Loup in Provence, "she enjoys everything as if she were 17 instead of 72" (qtd. in Nelson 68).

The following spring she was back on the Riviera again, this time staying at Hyères on the southern end of the Riviera. This was already well-known as a resort of French royalty, and Robert Louis Stevenson had lived there for a while — indeed, he said he wished he had died there. But the Queen was in deep mourning for the Prince of Wales's elder son, Prince Albert. Her second daughter Alice's husband, the Grand Duke of Hesse and the Rhine, had just died too. So this was a low-key visit, on which various constitutional affairs impinged. Nevertheless, Nelson makes even this fifth chapter interesting by including more anecdotal material, for example, about the occasion on which the Queen, having had a "slightly risqué" story repeated to her, said famously, "We are not amused" (78). He also supplies two lists, one of the places she went to visit, and the other of the people who came to visit her. As for the former, she clearly had remarkable stamina, and seems to have been fascinated by everything she saw, from the cork trees to the salt pans. In fact, she must have enjoyed her stay, because she stayed on longer than originally intended.

Visits to Nice

Left to right: (a) Hôtel Excelsior, Regina Palace, now in residential use (photomechanical print, Library of Congress Digital Gallery, reproduction number LC-DIG-ppmsc-05002). (b) "The Queen's Indian attendants," from Sarah A. Southall Tooley's The Personal Life of Queen Victoria (3rd ed. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1901, in the Internet Archive, p. 263). (c) The monument to Queen Victoria at Cimiez, by Louis Maubert, unveiled in 1912, a delightful reminder of the Queen's special love of the "flowery south" (cropped, with thanks, from Mwanasimba's photograph at Wikimedia Commons).

Queen Victoria's subsequent visits to the Riviera, from 1895-99, were all spent in Nice. She received a rapturous welcome on her first arrival there in March 1895, and felt very comfortable at the Grand Hôtel, and then (for her last three visits) in the new Hôtel Excelsior, Regina Palace, built with her needs in mind. Both hotels were a little away from the centre, in Cimiez, but she was as intensely engaged as ever in every aspect of her crowded life. Chapters VI through IX detail the many family, household and diplomatic incidents that marked these visits, as well as her usual round of outings and often colourful visitors. As always, Nelson is good on the wider background. These were the difficult years leading up to the second Boer War, and relations with Germany, France and Russia were all strained. The Queen was up in arms, for instance, when her grandson, Kaiser Wilhelm II, congratulated President Kruger on his successful resistance to the British-led Jameson Raid in the Transvaal. Lord Salisbury came to Cimiez three times during the 1886 visit that followed on from that affair. On those occasions they spoke also of what she called "the incredible behaviour of Russia, who was urging and encouraging France against us with regard to Egypt" (qtd. in Nelson 99). But she participated no less eagerly in the annual Battle of the Flowers on the Promenade des Anglais, and continued to entertain even those crowned heads whose policies bothered her. One such was her cousin Leopold, whom she had met once in her carriage on the road to Villefranche. This notoriously dissolute monarch, who earned the nickname "the Butcher of the Congo," would shake hands gingerly in order to protect his long fingernails. There is enough material here for ten historical novels.

One seam that has recently been developed elsewhere (see "Related Material" below) runs all through this part of the book. At Grasse, Queen Victoria had already been studying Hindustani. Since 1892, to her household's consternation, her Indian Munshi had actually been accompanying her on her Riviera trips. So instead of John Brown in his kilt and topee, the locals were treated to sightings of the tall, turbaned, domineering Abdul Karim and other "inferior" Indian attendants. Even the Aga Khan, on a visit to Nice, could not help commenting on the Queen's choice of retinue: "It seemed highly odd, and frankly it still does," he wrote in his diary (qtd. in Nelson 124).

A horse trough and drinking fountain on the way from Nice (uphill) towards Villefranche, donated by Queen Victoria, and naming also the local branch of the "Societé Protectrice des Animaux."

Nelson points out that the Queen's stays were getting longer and longer, and that in the end she spent almost a year of her life on the French Riviera. There is no way of quantifying the effect of her patronage on the area, but it was obviously an enormous one, and in the Epilogue we learn that in Nice, at least, people were dismayed when the crisis in South Africa, and French attitudes towards it, caused her to cancel her last proposed trip there. That was in 1900. Well might she grieve, too, for what she called the "sunny, flowery south" (qtd. in Nelson 149), for she would never return. It was the end of an era, marked by only a handful of tangible reminders, such as St George's Church in Cannes, with its replica of Prince Leopold's recumbent effigy at Windsor; the Prince Leopold Fountain, also in Cannes; and monuments to the Queen herself at both Menton and Cimiez, the latter an especially attractive group by Louis Maubert in white marble. But the most poignant reminder perhaps, and the one that tells most about the Queen, is an uncelebrated drinking trough at the top of the hill from Nice to Villefranche, which has the Queen's name on it as donor, along with that of the Society for the Protection of Animals at Nice. It is dated 1896, and one can easily imagine the animal-loving Queen feeling that some respite and refreshment should be available for her horses after pulling her up the steep slope. Perhaps there are other such troughs scattered around.

This enjoyable and knowledgeable book explores many aspects of the later Victorian period from a new angle, and in a new context. It is particularly illuminating on the relations between Britain and France at this time, an area to which not enough attention is paid — despite the Queen's own strong links with the last French royals (both Louis-Philippe and Napoleon III ended up seeking refuge in England), and the fact that the two countries fought as allies in the Crimea. Even French criticism over South Africa, referred to here by Nelson, did not stand in the way of the Entente Cordiale of 1904. Perhaps Queen Victoria's evident affection for France, and especially for the Riviera, was more important in the two countries' long love-hate relationship than is generally realised.

Related Material

- Review of Shrabani Basu's Victoria & Abdul: The True Story of Queen's Closest Confidant

- A Brief Notice of The French Riviera: A Literary Guide for Travellers

Bibliography

Nelson, Michael. Queen Victoria and the Discovery of the Riviera. New York: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, 2007. 204 + xiv pp. £11.99. ISBN 978-1-84511-345-2.

Strachey, Lytton. Queen Victoria. London: Chatto & Windus (Phoenix Library), 1928.

Last modified 24 June 2012