These are two short excerpts from a section entitled "The Cult of Games" in Chapter IX of Derek Winterbottom's Thomas Hughes, Thomas Arnold, Tom Brown and the English Public Schools (2022). They appear here by kind permission of the author. The book itself is fully illustrated, but these illustrations come from our own website. Click on them for more details about them. — JB

ne of the unintended results of [Thomas Hughes's] Tom Brown's School Days was that its enthusiastic and constant references to rugby, cricket, cross-country runs and "fighting" gave the impression that games were an indispensable feature of a great public school. As we have seen, games had not been a part of Arnold’s scheme, while Stanley, (the ultimate non-games player) barely mentioned them in his biography. But after the appearance of Hughes’s book in 1857 the popular notion of the public schoolboy as a manly and courageous sportsman was strongly re-inforced, linked to a growing panic in the second half of the century about the "sin" of male masturbation and same-sex relationships. Constant physical activity, it was thought, would exhaust young men and reduce the likelihood of self-abuse while it also had the advantage of strengthening the physique and promoting manly virtues such as courage and "patriotism," first towards one's own boarding house, then the school and finally the nation....

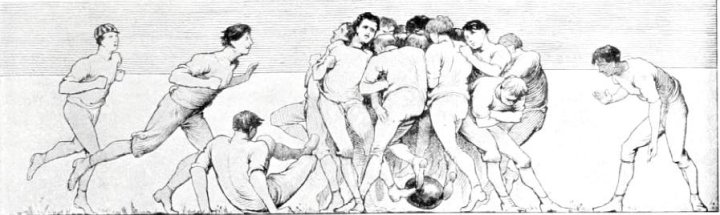

Rugby

Hence in the last three decades of the nineteenth century the public schools, while imagining, often through a misreading of Tom Brown, that they were following the example of Arnold, actually moved away from it by becoming places where athleticism came to be valued even more highly than academic success (see Mangan). "Playing the game" became the watchword of public school men, following the 1892 poem of Henry Newbolt, formerly a pupil at one of the new Victorian Rugby clones, Clifton College (see my Henry Newbolt..., 24,43, 86). Founded by the influential merchants of Bristol in 1862 its first headmaster was John Percival, a young man who had taught at Rugby for a few years under Frederick Temple and who was in many ways even more of a genius as a headmaster than Arnold. He started the school with 76 pupils and a "Close," a "Bigside" and "praepostors" and left it in 1879 with 680 boys and an outstanding record of scholarships at the universities. Percival was a genuine innovator: he set up a "modern side" as well as a classical side, he introduced science, opened a house for Jewish boys and welcomed day pupils and younger boys, but like Arnold he was a formidable personality who upheld the strictest standards of Christian morality.

Percival also helped to found Somerville College for women at Oxford as well as what became Bristol University, while continuing to support the education of working men from the inner cities. He was not a games fanatic but cricket became very important during his time at Clifton, as it did at other schools, and Newbolt wrote later that the only thing his contemporaries really cared about at school was a place on the first eleven. Rugby football was introduced to Clifton by a young Old Rugbeian master, Graham Dakyns, who arranged an away match with Marlborough in 1864 which is claimed to be the first inter-school rugby contest in England. The rules of the game had not yet been standardised, even to the point of how many players should take part, and the result was a battle rather than a match. The Marlborough captain asked Bradley whether he should abandon the contest, but the Master replied "Win the game first, and then talk about stopping if you like." Marlborough then dropped a winning goal and the match ended. Charles Tylecote, a notable Clifton sportsman, wrote later: "I was one of the football team that went to play against Marlborough. What a match it was! You could hardly call it football.... However, after we had changed and had a good supper all together, we were all on quite friendly terms." The fixture was not resumed until 1891, by which time the fifteen-a-side game had been standardised (Christie 272, 273).

Percival left Clifton in 1879 to become president of Trinity College at Oxford, then headmaster of Rugby. This was because the governors knew that the school had become slack under Hayman and Jex-Blake and had lost the pre-eminent position it had enjoyed under Arnold and Frederick Temple. Morale and standards had fallen and Percival, a renowned disciplinarian, was brought in to restore both. It was during his time there that he famously ordered that rugby shorts should not expose muscular thighs, which shows how much he (and other heads) had become fixated on the issue of sex (see Potter 192, 193). Rugby’s profile was helped by the fact that two of its former headmasters (Tait and Temple) became archbishops of Canterbury but after the Hayman affair it lost some of its appeal, to the advantage of Eton and also Harrow. Westminster had ceased to be popular because the industrial fogs of London were becoming a menace and the city’s sewage system was totally inadequate, leading to a stinking River Thames, especially when the tide went out.

Cricket Match at Winchester between Eton and Winchester Colleges (1864).

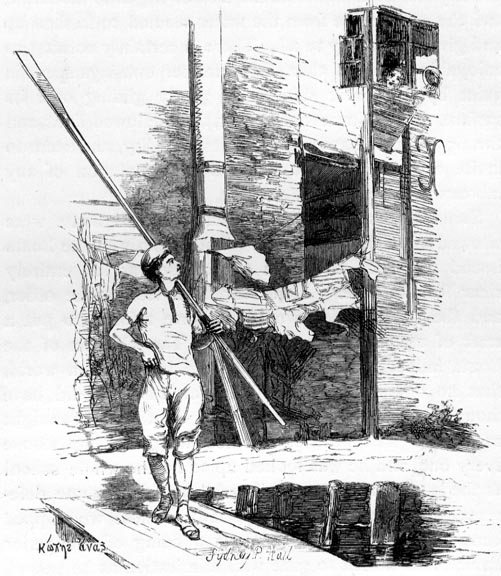

Cricket was the paramount game in the later Victorian public schools and the annual match between Eton and Harrow became a major social institution, attracting tens of thousands of spectators. The only challenge to cricket as a summer sport was rowing in the relatively few schools which were close to suitable water. Eton and Westminster boys had begun to go boating on the Thames towards the end of the eighteenth century and the first inter-college race at Oxford took place in 1815, the first Oxford v Cambridge Boat Race in 1829 and the first Henley Regatta ten years later. By the time Tom Brown at Oxford was published in 1859 rowing was already popular in the rowing public schools and the universities and it steadily became the dominant university sport as the century wore on.

James Hornby, while a fellow of Brasenose, rowed in his college eight, the Boat Race and at Henley. In 1868 he was appointed the first head master of the newly-reformed Eton and was naturally well-disposed to the efforts of his junior colleague Edmond Warre, who had been an outstanding rower as an Eton schoolboy and at Oxford. Warre returned to Eton in 1860 and became one of the first assistant masters to devote a great deal of time and energy to the coaching of their sport, as a result of which Eton crews came to dominate school rowing. Warre succeeded Hornby as headmaster in 1884 and remained in post for nineteen years, a physically impressive figure who came to personify what had by then become a national obsession with athleticism.

Left: "The Master of the Oars." Right: Ruby Levick's sculpture, Rugby Football.

In 1900 a Rugby master, J.H. Simpson, felt able to write that the popular impression in Britain was that the public schools were "primarily places where boys learn to play games" and that this was broadly true (Gathorne-Hardy 151). The increasingly worldwide British Empire was said by the wits to be the sphere where blacks were ruled by Blues and the latter took with them the British obsession for sports. The rules of association football were agreed in 1863 and the rules of rugby were standardised under the Rugby Football Union in 1871. Many schools which had begun to play association football switched to rugby towards the end of the century, though these tended to be the new foundations: Eton, Westminster, Winchester, Shrewsbury and Charterhouse all remained loyal to "soccer." More than a century later the historian Jonathan Gathorne-Hardy felt justified in claiming that "Britain’s most significant contribution to the world at the present is not parliamentary democracy but the football, cricket and athletics invented by her public schools" (166). If this is true, and if the Tom Brown book played an important part in this process, then the legacy of Thomas Hughes has been immense.

Links to Related Material

- Thomas Hughes on the value of team sports in secondary education

- "Let the remembrance of it take care of itself" — Thomas Hughes on the transience of athletic fame

Bibliography

Christie, O. F. A History of Clifton College, 1860-1934. Bristol: Arrowsmith, 1935.

Gathorne-Hardy, Jonathan. The Public School Phenomenon. 1977. London: Penguin, 1979.

Mangan, J. A. Athleticism in the Victorian Public School. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981. (A detailed study of six schools: Harrow, Lancing, Loretto, Marlborough, Stonyhurst and Uppingham.)

Potter, Jeremy. Headmaster, the Life of John Percival, Radical Autocrat. London: Constable, 1998.

Winterbottom, Derek. Henry Newbolt and the Spirit of Clifton. Bristol: Redcliffe Press, 1986.

_____. Thomas Hughes, Thomas Arnold, Tom Brown and the English Public Schools. Isle of Man: Alondra Books, 2022. Freely available for reading on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/winterbottom-thomas-hughes/mode/1up

Created 1 October 2023