Left: Marquis of Salisbury. Sir John Everett Millais Bt PRA (1829-96). 1883. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London NPG 3242 Right: Marquis of Salisbury. Photographer: Eliott & Fry. Click on images to enlarge them.

Robert Gascoyne-Cecil served three times as Prime Minister: from 23 June 1885 to 28 January 1886; from 25 July 1886 to 11 August 1892; and from 25 June 1895 to 11 July 1902 The third son and fifth child of six of James Brownlow William Gascoyne-Cecil and his first wife Frances Mary Gascoyne, he was born on 3 February 1830 at Hatfield House. However, their second son died at the age of two, leaving Salisbury effectively as the second son. The family was descended from the first Lord Salisbury, the son of Lord Burghley who was Elizabeth I's minister.

Salisbury was educated by a private tutor and briefly attended a boarding school near Hatfield; between 1840 and 1845 he was a student at Eton but he was removed because of constant bullying and again had a private tutor at Hatfield. In 1847 he was admitted to Christ Church, Oxford, and was awarded his Degree in 1850; in 1853 he obtained a fourth class Degree in maths and an MA in 1853.

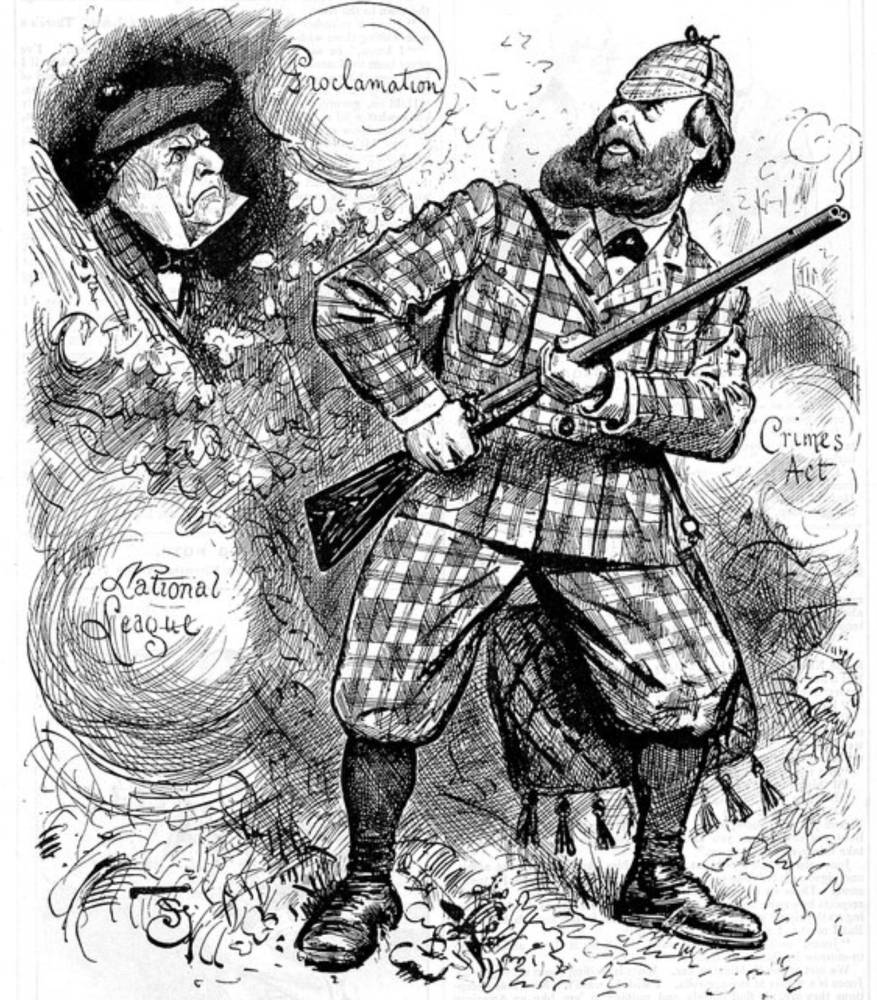

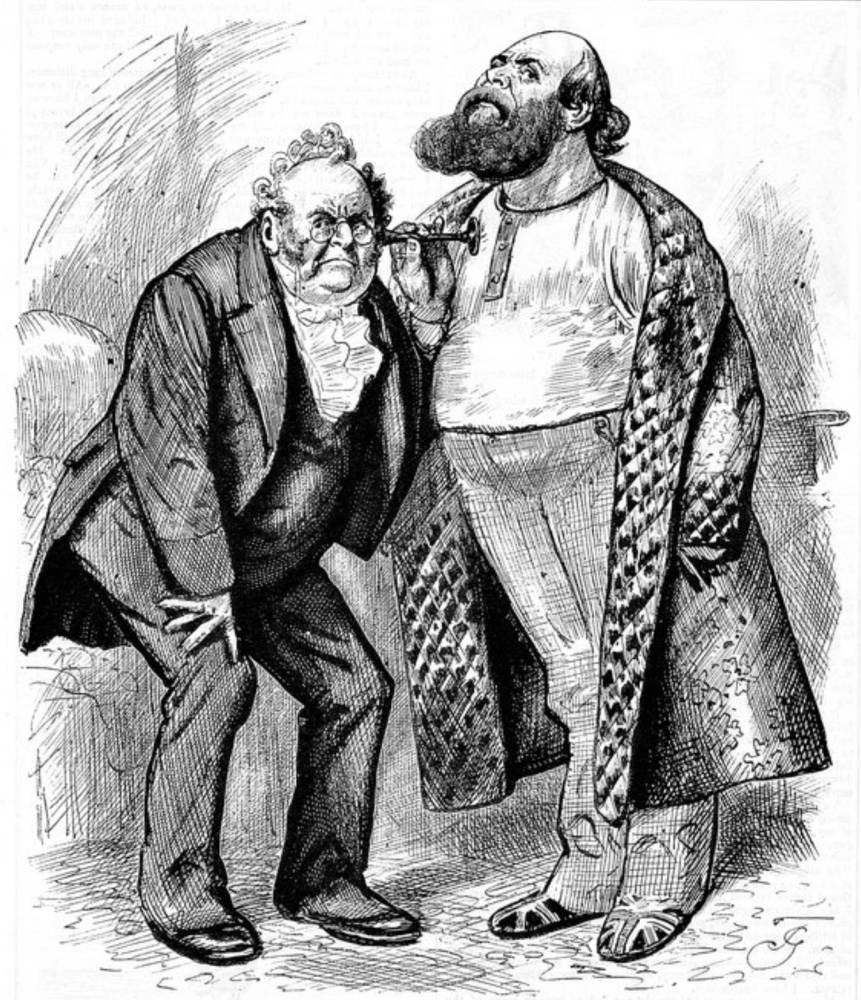

Four editorial cartoons featuring Salisbury from Fun by John Gordon Thomson (1841-1911). Left: Packing Up. Middle left: Caught in the Act. Middle right: In a bad way. Right: At Last.

Between July 1851 and May 1853 he visited South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand, and soon after his return was elected as MP for Stamford. He made his maiden speech in April 1854. On 11 July 1857 Salisbury married Georgina Alderson, the daughter of a judge, despite his father's opposition. Consequently, his father refused to increase his son's allowance and Salisbury was obliged to become a journalist to earn enough money to keep his family. He wrote articles on a regular basis for Bentley's Review and the Tory periodical the Quarterly Review. In April 1850 he entered Lincoln's Inn, but his financial situation did not become secure until the death of his elder brother in 1865 at which point Salisbury took the courtesy title of Viscount Cranbourne and became heir to the wealth and estates of his family.

Hatfield House in Hertfordshire: the home of the Cecil family.

In July 1866 he was appointed as Secretary of State for India in Lord Derby's third ministry and was also made a Privy Counsellor; however, he resigned from the government in March 1867 because he opposed the extension of the franchise proposed in Disraeli's second Reform Bill. In March 1868 he spoke against Gladstone's proposal for the disestablishment of the Irish Church; it proved to be his last speech in the Commons because his father died the next month and Salisbury succeeded to the title and a seat in the House of Lords.

In the general election of 1874 the Tories won a majority, and Disraeli became PM; Salisbury was appointed as Secretary of State for India once again although relations between the two men were not always easy. In December 1876 Salisbury was sent as Britain's representative to the Six Powers' conference on the Eastern Question in Constantinople [Istanbul]. Although the conference ended in the failure of the Powers to find a solution, it was clear that Salisbury had made a good impression on other European leaders. On the resignation of Lord Derby in April 1878, Salisbury was appointed as Britain's Foreign Secretary but before he took up his post formally, he issued the 'Salisbury Circular' to other European powers on why the treaty of San Stefano — agreed between the Ottoman Empire and Russia — should not be accepted by Europe. Consequently, the Congress of Berlin met between 13 June and 13 July 1878, hosted by Prussia under the auspices of Count Otto von Bismarck. Salisbury and Disraeli, who attended on behalf of Britain, claimed to have returned with 'peace with honour' for Britain following the signing of the treaty that supposedly settled the problems in the Balkans. For his efforts, Salisbury was created a Knight of the Garter.

On the death of Disraeli in 1880, Salisbury assumed leadership of the parliamentary opposition in the House of Lords to Gladstone's Liberal Government. The same role in the Commons was filled by Sir Stafford Northcote: the two men were deemed to be a dual leadership of the Conservative Party in the country. In October 1883 Salisbury published (anonymously but recognisably) an article in the Quarterly Review on the dangers of radicalism: this was during the process of framing the third Reform Bill. Gladstone's government was brought down on a vote over the Budget and Salisbury accepted office as PM on 23 June 1885. He then decided to take on the role of Foreign Secretary as well. In the December general election he failed to win a majority: the results were as follows:

Liberals — 335

Conservatives —249

Irish Nationalists —86

Shortly afterwards the government was defeated over the issue of the 'three acres and a cow' amendment to the Queen's Speech on 28 January 1886. The reality of the debate was not on whether every person should be entitled to the 'three acres and a cow' but on whether Ireland should be granted Home Rule. However, Salisbury returned to power within the year, following the defeat of Gladstone's bill for Irish Home Rule with his party reinforced by the addition of Joseph Chamberlain's "Liberal Unionists": Liberals who opposed Gladstone's attempts to give home rule to Ireland. Salisbury's Chancellor of the Exchequer was Lord Randolph Churchill — father of Winston Churchill — nother unpredictable ally. Salisbury was reported as saying, 'I have four departments —the Prime Minister's, the Foreign Office, the Queen and Randolph Churchill; the burden of them increases in that order'. In December 1886 Churchill resigned after a series of differences with Salisbury: it is thought that he did not expect his resignation to be accepted and was most surprised when it was. Salisbury's habit of appointing his family to positions of power is thought to have been the origin of the expression, "Bob's your uncle": in 1887 he appointed his nephew Arthur Balfour as Chief Secretary of Ireland.

In 1888 the government passed the Local Government Act, which created County Councils that were responsible for local administration. The following year the British South Africa Company was granted a Royal Charter to colonise an area in central east Africa that ultimately became Rhodesia with its capital at Salisbury [now Zimbabwe and Harare respectively]. Salisbury attempted to avoid alignments in European affairs, maintaining the policy of what was later called “splendid isolation.” Colonial affairs, however, brought difficulties with some of the European powers.

- an Anglo-German agreement in 1890 resolved conflicting claims in East Africa: by the agreement, Great Britain received Zanzibar and Uganda in exchange for Heligoland

- a treaty with Portugal in 1891 gave Britain further rights in East Africa.

- the Fashoda Incident of 1898 brought Britain and France to the verge of war but ended in a diplomatic victory for Britain.

- difficulties with the Boers-Dutch settlers in southern Africa who had attempted to escape from British rule-resulted in the Boer War of 1899--1902

- Salisbury conciliated the United States at the time of the

- Venezuela Boundary Dispute (1895)

- the Spanish-American War

- the Panama negotiations

In 1891 his government passed an Education Act that introduced free elementary education but the general election of 1892 resulted in a small majority for the Liberals; Salisbury resigned and Gladstone formed his fourth and last ministry, retiring finally in March 1894 to give way to Lord Rosebery. Rosebery's ministry was defeated in 1895 on a vote on the Army Estimates and Salisbury formed a coalition government with the Duke of Devonshire and Joseph Chamberlain until an election could be held. Chamberlain had taken a substantial number of Liberal MPs over to the ranks of the Conservatives because they disagreed with Gladstone's attempts to give Home Rule to Ireland. Having split the Liberal Party in the 1880s, Chamberlain went on to do the same to the Conservative and Unionist Party in 1903.

This ministry passed the Workmen's Compensation Act in 1897 and a Local Government Act for Ireland in 1898. In the reconstructed administration of 1900 there were so many of Salisbury's relations holding office that it was nicknamed the 'Hotel Cecil'. During this part of the ministry, relations with the Boers living in the South African Republic (the Transvaal and the Orange Free State) deteriorated over the rights of the "foreigners" to vote: Paul Kruger had no intention of allowing the Boers to be outnumbered by other settlers. In October 1899 the Boer War broke out, ending only in May 1902 with the Treaty of Vereenging.

As his health failed, Salisbury handed over the Foreign Office to Lord Lansdowne; in July 1902 he resigned as PM on the grounds of ill health and was succeeded by his nephew, Arthur Balfour. Salisbury died on 22 August 1903 at Hatfield House. He was 73 years old.

Recommended Reading

Cecil, D. The Cecils of Hatfield House. London, 1973.

Kennedy, AL. Salisbury 1830-1903: Portrait of a Statesman. London, 1953.

Roberts, Andrew. Salisbury, Victorian Titan. 1st ed. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1999. Now available in paperback from Faber, 2010. 984pp. [Reviewed by Joe Pilling]

Taylor, R. Lord Salisbury. London, 1975.

Created 20 March 2002; last modified 25 January 2015