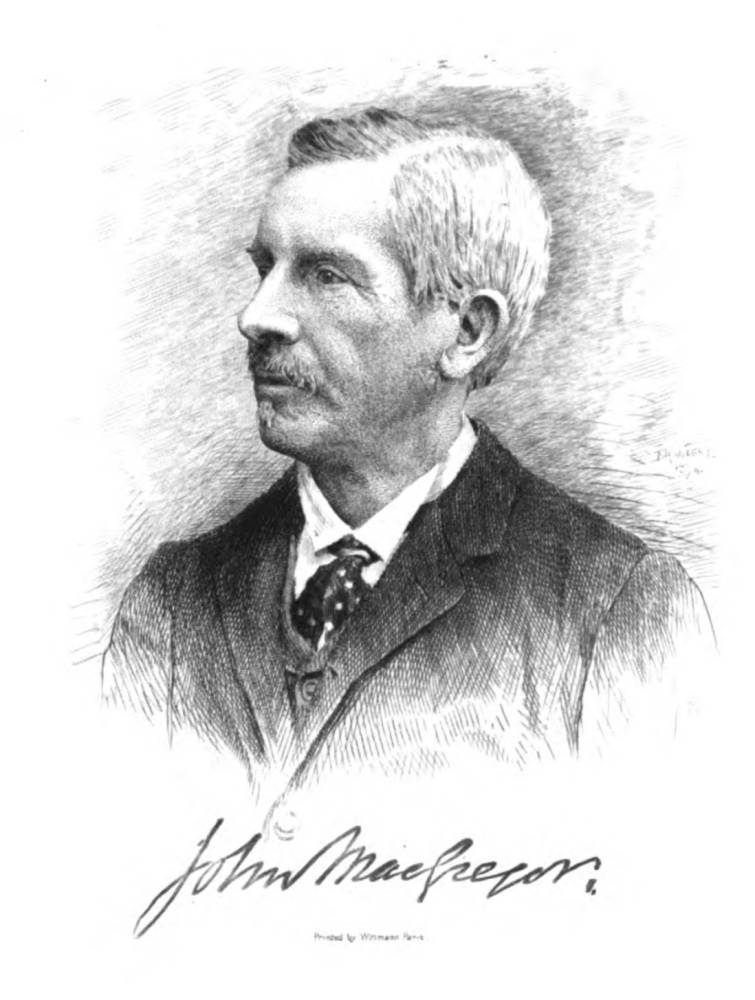

John Macgregor by H. Manesse from Stodder’s biography. Click on image to enlarge it.

hroughout the ages there have been pioneering individuals who have been prepared to risk life and limb to reach uncharted parts of the globe. Although only a small number of these explorers achieved worldwide fame, there were many others who were once household names, but have now largely been forgotten with time. One such figure from the Victorian period was the remarkable adventurer and philanthropist, John MacGregor. He may not have been a trailblazer who reached undiscovered parts, but perhaps what was most striking – not to mention unusual – about his exploits was that, unlike the vast majority of those we consider to be ‘intrepid’ pathfinders, he did much of his travel completely alone with only his small canoe, Rob Roy, for company.< This article seeks to remind people about this once famous explorer, who, as well as inspiring many Victorians and shaping their leisure tastes, committed much of his life to trying to improve the life of others.

John MacGregor (‘Rob Roy’) was born in Gravesend on 24 January 1825 to Major Duncan MacGregor, a Scottish soldier from a clan renowned for fighting, and Elizabeth, the daughter of a Baronet. As you might expect from his background, he not only received a good education but he grew up to be a ‘manly boy’ who enjoyed physical activity and travelling. He also shared his parents’ strong Christian faith, which was the driving force for much of his life’s work. Indeed, one reason he is such an interesting historical figure is that he epitomised two prominent traits that we often associate with the Victorians: Muscular Christianity and evangelical philanthropy.

Early drama afloat: Shipwrecked and Shipwrecked Again

It is perhaps surprising what Rob Roy later became famous for, given that he had a fraught relationship with boats from a very young age. Although he may not have been that aware of it, when MacGregor was only two weeks old, he experienced incredible danger and drama on board the ship Kent. The vessel had set out to take his family to India, where his father had been posted, but upon entering the Bay of Biscay a fire broke out that eventually breached the hull. As the fire and water overcame the vessel, which carried munitions on board, MacGregor Senior played an important role in trying to orchestrate an orderly evacuation in these desperate and chaotic scenes. Indeed, he later described the experience as the closest a human being could get to death without tasting it, since it looked completely hopeless on a number of occasions, which is why he preached Christ crucified to those on board. During the dangerous and protracted evacuation three of the six heavy-laden lifeboats sank, and ninety people lost their lives Incredibly, the majority of passengers did manage to escape to the safety of another vessel. Some of the younger survivors died in cramped conditions during the 400-mile journey back to Falmouth, but the exhausted MacGregors made it back safely with only a small amount of sugar used to feed Rob Roy.

The Burning of the “Kent’ East Indiaman. Thomas M. Henry/ From Hodder.

That terrible voyage would not be their last brush with danger at sea. Some months later, Elizabeth and her baby were almost lost again, this time travelling from Edinburgh to London during a storm. In the aftermath of that experience, Mrs MacGregor was greatly comforted by a visit from the celebrated poet, Hannah More, who wrote the following lines for ‘little Rob Roy’:

Sweet babe twice rescued from the yawning grave,

The flames tremendous and the furious wave,

May a third better Life thy spirit meet,—

E’en Life Eternal at thy Saviour’s feet.

MacGregor’s life at sea was indeed better, although, at the age of fifteen, he had one close shave when he had to be rescued from his sinking yacht – his ‘second shipwreck’, as he called it, outside the harbour of Kingstown near Dublin.

Cambridge and his early career

Rob Roy was not exceptional academically, but he was a hard worker able to get into Cambridge University, where one of the many activities he enjoyed was rowing. Furthermore, from 1845 onwards, he began to commit more time to writing as a regular contributor to both Punch (with the proceeds given to the Ragged School movement) and Mechanic’s Magazine.

His peers knew him for his strong Christian principles, but although he had aspired to become a missionary and had also considered civil engineering, his scientific interests led him to London to study for the bar, specialising in patent law. It was during his time in the capital that he became heavily involved in philanthropy, whilst also being able to embark on some lengthy trips abroad, including an eight-month tour of Europe and the Middle East in 1849.

He became heavily involved with the early Ragged School movement and he not only helped to train the teachers, but was also instrumental in launching their Shoeblack Brigade, which provided an important source of income for many destitute children. It was during a trip to a school in 1853 that he encountered an open air mission, which inspired him to take up street preaching. Indeed, he wrote a pamphlet that offered advice on the matter, entitled ‘Go Out Quickly’, which sold over 100,000 copies.

He was not someone to shy away from confrontation, as he often engaged with those who took different viewpoints from him, included some prominent secularists. He developed a sophisticated apologetic for his Christian faith, which was informed by his keen interest in science and literature.

MacGregor was a ‘man of marvellous energy’, who was much sought after, because of his gifts. He was a quick worker and methodical planner with a strong sense of honour, duty, and obligation, which led him to throw himself wholeheartedly into his many activities, no matter what he did. As his biographer pointed out, ‘he would not offer to the Lord that which cost him nothing’. His diary entry of 31 December 1855 captures some of the business-like fashion by which he conducted his work, as well as the breadth of the activities he was already involved with:

The time finds me at work on the Protestant Alliance, Church of England Young Men’s Society, Open air Mission, Lawyers’ Prayer Union, C. T. Mission, Scripture Readers’ Society, Ragged School Union, Shoeblack Society, Pure Literature Society, Boys’ Refuge, Reformatory Committees, Protestant Defence Society, Field Lane School, Scripture Museum, &c.

In the aftermath of the Crimean War, he also helped to support the military through the London Scottish [Rifle] Volunteers. He believed such activity was good for young people, as it helped them overcome the deadly enemies of idleness, dissipation and vice.

Through his work, he became closely acquainted with many others who shared his interests, including Lord Shaftesbury, Lord Kinnaird, and Alexander Haldane. Bishop Wilberforce, who met with him, described him as ‘a curious specimen of earnest, evangelical, Protestant men, very narrow and earnest, ready to burn a Tractarian or spend himself in preaching the Gospel to the poor.’ Indeed, one of his achievements was helping to get a permanent memorial for William Tyndale erected by Victoria Embankment.

As a keen traveller, he was also concerned about overseas mission. He provided illustrations for one of the books on the topic written by the famous explorer Dr David Livingstone, whom he had met in Dublin. MacGregor also went on a preaching tour of North America in 1859 during which he spent a lot of time speaking with black Christians. He even made the astute remark that ‘There will one day be a Civil War here about these slaves’.

In 1862, MacGregor reflected on his life and the question of why he had experienced so few trials, if he was a child of God. He noted that he had enjoyed everything in life and that, amongst other things, he had been blessed with health, strength, financial security, and the opportunity to enjoy no fewer than twelve foreign tours. He acknowledged that he could have become rich by working harder, or more learned by greater study, or even more holy by praying more often, but he pointed out that he had overcome his previous desire for distinction by focusing on an ‘unobtrusive, gentle, humble piety’. Nevertheless, he also acknowledged that his life had reached a kind of plateau, which is an interesting backdrop for the change of direction that he was about to embark on.

The Rob Roy canoe: the first voyage

MacGregor in Rob Roy. From Hodder.

In 1865, MacGregor decided to go on a solo canoeing trip on a boat he had commissioned from Searle’s of London. The design, which the canoes of North America and Kamschatka inspired, was about 15ft long by 2ft 6inches (at its widest part) and had a four-foot elliptical hole, where he could be seated (and where a bag could be stowed). The craft, which now resides in the River and Rowing Museum in Henley, was built from oak with cedar decking. It had a two-bladed Indian paddle and weighed about 90lbs (with mast and sails). He flew the Union Jack from it and had ‘Rob Roy’ written on the stern. He later explained that the idea of a voyage in such a boat had been germinating since 1848, when Archibald Smith showed him an India-rubber boat that could be a tent, boat. and bed.

His journey started on 9 July 1865, when he paddled down the Thames to Sheerness. His trip of almost a thousand miles lasted nearly three months and took him over the Meuse, Rhine, Danube and Moselle rivers, as well as some of the lakes of Switzerland. He paddled for much of the journey, although he had to rely on other forms of transport for certain parts of the trip, such as trains and carts. In some of the places, crowds turned up to watch him depart and in one location in the Black Forest, a group of locals even protested about his plan to cross a lake, because Pontius Pilate was said to be at the bottom of the water and would drag the boat down! His week-by-week accounts were published in the Record and by the time he arrived back at Westminster Bridge on 7 September he had become the ‘hero of the hour, and all the world talked of him and his exploits’.

Although he had written about some of his earlier travels, the interest in this particular trip ensured that there was a ready market for a book on the topic. A Thousand Miles in the Rob Roy Canoe on Twenty Rivers and Lakes of Europe, which featured twenty of his own illustrations, was released in January with any profit being donated to the Shipwrecked Mariners’ Society and the National Lifeboat Institution. This turned out to be a considerable amount, since the book was sold out by the following month and a month after the second edition was released, which sold 2,000 copies within five days, a third print run was required.

MacGregor probably did more to popularise canoeing than any other individual at a time when pleasure boating and camping were becoming very popular. The Spectator noted that he had elevated the pastime to ‘to the rank of a national institution, so that it reflects the most genuine sides of the English character’. Indeed, the type of boat he used became known as a ‘Rob Roy canoe’ – what we would now call a kayak – and it could be ordered from most boat-builders. Moreover, he didn’t just encourage the activity through his literary output, but he also formed the Canoe Club (now the Royal Canoe Club) in 1866, which in turn led to the formation of other organisations around the country. Nor was impact only national, for the French Emperor, Napolean III, was inspired by his work to organise an exposition of pleasure boats, as well as a regatta.

Despite his burgeoning fame, MacGregor kept himself grounded not only by remembering the hospitals of London and ‘the squalid poor in fetid alleys’ but also by remaining focused on the battle he was fighting against ‘vice, sadness, pain and poverty’. He concluded that it was not right for a ‘true Christian soldier’ to enjoy such comfort, scenery and health, ‘unless to get vigour of thought and hand, and renewed energy of mind, and larger thankfulness, and wider love, and so, with all the powers recruited, to enter the field again more eager and able to be useful’.

Rob Roy: the second trip

Whilst many people were starting to read about MacGregor’s exploits from the previous year, he already planned his next summer’s voyage – this one to Scandanavia in a slightly smaller canoe. The 14 foot craft (with a beam of 2 feet 3 inches) weighed only 60 pounds and was again commissioned from Searle. It would survive a serious cart accident, a close encounter with a whirlpool at Trolhatta, and even being pursued down the Elbe by natives armed by bludgeons and axes, who had been told that MacGregor was a ‘wild Chinaman being chased’. His journey was, once again, roughly one thousand miles, but this time the journey took just under two months. The excursion, which involved trips on twenty-five steamers and six railways, cost him £45 and by December the book describing his adventure had been released.

Although many people eagerly read about MacGregor’s exploits, his mode of transport polarised opinion. Some suggested that it was a mistake to use a canoe when a steamboat could carry you whereas others pointed out that the boat was only supposed to be used on waterways that were inaccessible for other craft. There was even concern that an ‘upstart’ vessel designed by savages was usurping the rightful place of other traditional craft, such as the trusty British gig. Others noted that the canoe was uncomfortable for the legs and only ‘confirmed the suspicions of many Europeans about the constitutional eccentricity, not to say madness of Britons’. Indeed, MacGregor was even depicted as having gradually become a sort of aquatic centaur with the lower part of his body being the boat!

MacGregor was well-aware of some of the criticism, but as a former rower, he felt that he was in a good position to judge the merits of different craft. He ‘infinitely preferred the canoe’, as he believed the sitting position to be more comfortable, and the boat was not only more straightforward to control (aided by facing forwards), but you could haul it easily, it was safer to travel in, and you could sleep in it. When asked if it would have been preferable to travel with someone else, he responded by saying, ‘Not for me, if he was to be in the boat, and not for him, if he had to run on the bank’. On another occasion, he was amused to be asked whether his trips had been a waste of time by someone who admitted that he had spent his entire vacation in one spot: Brighton.

Rob Roy Yawl & Rob Roy in the Middle East

In 1867, for the third consecutive summer, MacGregor undertook another journey, although this was unlike the others, as it was not in a canoe. Instead, he took to the potentially more dangerous waters around the coast of France aboard a 21-foot sailing yawl, which involved some stormy conditions and sleepless nights.

MacGregor’s final excursion on board Rob Roy occurred in the autumn of 1868, which his biographer described as ‘without doubt the greatest tour that John MacGregor ever made’ used canoe a very similar to that of his Baltic trip, although it was an inch narrower and the top-mast was made from the second joint of a fishing rod. His journey, which began in Egypt and travelled around the Holy Land, proved to be a much more perilous proposition than Europe, since he not only encountered more dangerous animals, including crocodiles, wild dogs, and boar but also a number of attempts made to capture him. He was pursued by the Arabs of Hooleh for some time, and although he managed to repel a number of them with his paddle, he was shot at and his canoe was finally apprehended and carried (with MacGregor still in it) to the local sheik. After an amusing incident in which he thumped the leader on the back, having offered him salt to eat, which he mistook for sugar, he was able to secure his release with only a small bribe. His book was unsurprisingly a runaway success with 2,000 copies ordered before the publication date and 5,000 of them sold within a fortnight.

MacGregor was unique, and his biographer noted three features that were particularly unusual. First, he was described as a ‘tourist Evangelo-tractual’, since he would constantly give out Christian tracts on his travels. Indeed, when he travelled on his yawl, for example, the boat’s cargo consisted of tracts, periodicals, books, Bibles and Testaments, which he gave out to the sailors of all nations. Secondly, he would not travel on a Sunday, which often surprised his on-lookers, and he would even sometimes disembark from a steamboat, in order to observe the day of rest. Thirdly, he was always speaking and writing about religion, which drew criticism from some. Nevertheless, the English and foreign press were all unanimous in agreeing that his writings were always full of interest, amusement and information.

MacGregor received so many requests to speak, that he decided he to use the opportunities to raise the considerable sum of £10,000 for charity. In 1870 alone, he lectured or presided at public meetings 128 times, which included giving his Rob Roy lecture fifty-six times, thereby raising £4,160. Although, unsurprisingly, he had to subsequently reduce his output, he finally reached his target on 8 March 1878, having only once cancelled an event because of ill-health. His biographer summed up the immense effort by saying

Surely, when the philanthropic history of this country is written, this fact should stand out as a lasting memorial to MacGregor. Many have written cheques for thousands of pounds to be distributed among the poor; few have given up time, strength, and convenience and endured the exhausting fatigue, the personal exposure and the wear and tear of life to accomplish so earnest a purpose.

It is perhaps misleading to describe MacGregor’s talks as ‘lectures’, since he delivered them in a highly unusual and entertaining way. Accompanied by a full-sized model of Rob Roy on stage, he would give his introductory speech before retiring and then re-appearing in his canoeing outfit, consisting of a red serge Norfolk jacket (or grey, if in enemy country), a light helmet and a flowing puggaree to protect his head and neck from the heat. When describing his camel rides in the Middle East, he would not only don a scarlet tunic and turban, but he would also straddle a chair (whilst holding an umbrella) to depict the movements of the rider, whilst making noises to express the emotions of his trusty stead, such as anger at being loaded, pleasure at drinking water, etc. It was not only the sights and sounds that the audience got to experience, but also some of the smells, as, on stage, he might smoke a chibouk pipe or burn a small portion of mummy dust to demonstrate how much creosote was used in the embalming material. When discussing eastern music, he would say that he was going to fetch a petulant Arab boy from behind the screen, only to re-emerge himself in costume in order to perform. According to his biographer,

He was wont to conclude his lecture on the Jordon with his famous ‘crocodile story’; then tying his bed on his back, putting on a Greek cap, and arranging his mosquito screen and oil cloth, he would light his lamp and lie down comfortably in the canoe, reading a copy of the Times. Suddenly the howl of a jackal would ring across the room, and MacGregor would spring up, tell in an excited way of a dreadful dream about an encounter with a crocodile, when forthwith the animal would appear on canvas at the back of the platform, with MacGregor riding triumphantly on its back, and ‘God save the Queen’ and ‘’Success to the Institute’ inscribed above and below the head and tail!

The Explorer Marries

Although he was a person who delighted in surprising his audiences, a decision he made in 1873 caught even some of his closest friends unawares. Whilst en route to the Azores, he cut short his journey to return home, after he had come to the conclusion that he wanted to marry Annie Caffin, whom he claimed to have ‘loved eight years in silence’. Many people were taken aback by the news, as they had assumed MacGregor, who was in his late forties, would be a lifelong bachelor. On their wedding day at St John’s in Blackheath around a thousand people attended with many more congregating outside. He halted his lectures for two years and the couple were delighted when the first of their two daughters, Annie, was born in 1875.

One can gain an indication of how high Rob Roy’s star had risen by the sheer number of notable individuals with whom he had contact. He not only met in person many influential figures, including the Prince of Wales and Lord Kinnaird, but he corresponded with many more, including the author Samuel Smiles and the Pre-Raphaelite artist John Everett Millais. He influenced a Tennyson poem and his work was also the inspiration for a Charles Dickens character. He met members of the Cambridge Seven before they set out to China and he even assisted the celebrated explorer, Henry Stanley, by giving him a short letter of introduction to Dr Livingstone. When he was mistakenly sent a letter from Charles Spurgeon that was supposed to go to another MacGregor, the well-known preacher pointed out that it had been his fault ‘for being so famous’!

Yet despite all of this, his biographer claimed that perhaps the most influential part of his work was the ‘unpretentious, quiet, helpful aid he gave to obscure boys in obscure places, and at all times’, when no applause or recognition was to be gained. It was ‘quiet, continuous, self-sacrificing work, having for its sole reward the opportunity of saying a word that should bring perchance new hope and aspiration to a weary life drifting away with the strong current of evil’. Indeed, he was a strong advocate for what became the Industrial School’s Act of 1866 and he continued to be a tireless supporter of organisations that were close to his heart, from the London School Board and the Pure Literature Society to the Fund to the Royal Humane Society and National Lifeboat Society.

MacGregor’s health remained relatively strong until he reached his sixties. After enduring four years of illness, he finally passed away on 16 July 1891. His friend, Lord Shaftsbury, was a pall-bearer at his funeral and he was buried in Bournemouth cemetery, alongside Canon Carus and Earl Cairns.

It is hard to summarise the legacy of John MacGregor, since he was someone who impacted many people’s lives in the Victorian period, particularly ‘young men of all classes’. His biographer noted that ‘He believed in pressing everything into the highest service’, whether it was a musical voice, a volunteer’s uniform, a canoe paddle, the power of entertaining or one’s professional calling – no matter what the gift might be, he believed ‘it came from God, and was ready for His using’. Indeed, nothing was said to have pained him more ‘than to see young men with splendid qualifications squandering them upon selfish indulgences and meaningless pleasures’.

Despite his considerable accomplishments, he remained a humble man who ‘was ever ready to recognise and appreciate the good that existed in others’ and who was keenly aware of his own short-comings. At times, he could be a little abrupt and self-asserting, but this came from his acute awareness of ‘power and purpose’. In an age when people often seek fame for its own sake, it is perhaps fitting to remember someone who committed so much of his life to helping others with ‘splendid courage, a dash of audacity now and then, a touch of recklessness here and there, admirable discretion, indomitable pluck, readiness of resource, and persistent determination’. Quite simply, he ‘was a man of no ordinary type, but a unique and remarkable personality, a brave, honest, and gifted man, who lived a life of patient well-doing and left the world better than he found it’.

Bibliography

Hodder, Edwin. John MacGregor (‘Rob Roy’). 3rd. ed. London: Hodder Brothers, 1894. Hathi Trust Digital Library copy of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 12 May 2020.

Last modified 12 May 2020