The Nemesis Steamer Destroying Chinese War Junks, in Canton River (1842). [Click on thumbnail for larger image and article from The Illustrated London News.]

uperior British military technology played an important role in the Chinese Opium Wars, enabling a mere commercial firm owned by stockholders to defeat the naval forces of a nation that described itself as the Middle Kingdom — a country, that is, of such superiority to all others that it served, or so its rulers proclaimed, as the mediator between heaven and earth. Characteristically, at the core of this British military superiority lay iron and steam, the key components of that Industrial Revolution that, for a time, made Great Britain both the world's leading naval and economic power. The embodiment of British capitalism, enterpreneurship, technology, and the ability of its merchants to force their will on what had once been the world's greatest empire was the Nemesis, a long, narrow flat-bottomed steamboat that proved not particularly seaworthy but perfectly suited to what later become known as gunboat diplomacy. Adding to the ability of this this ship to serve as a particularly apt symbol of the industrial north's contribution to the British empire, the Nemesis was built in Liverpool shipyards and "launched on the Mersey late in 1839 by John Laird for the Secret Committee of the East India Company."

The technological novelty of this warship, Peter Ward Fay explains, lay in its use of iron:

Except for deck, spars, and sundries, she was built entirely of iron. If that were not novelty enough, her dimensions and some of her fittings were unusual too. She was long in proportion to her beam, 184 feet against 29 if you forgot the paddle boxes, and her bottom was almost perfectly flat. This, though it held her draught to a maximum of six feet (much less if she was lightly loaded), guaranteed that she would slip dreadfully beating to windward, so she was equipped forward and aft with centreboards in open cases, each capable of being lowered by a hand winch to a depth of five feet. Her rudder was equipped with an equivalent movable extension. She was two-masted and rigged fore-and-after. Just behind the paddle boxes, which were connected by a raised platform that served as a bridge, rose a single tall funnel. Two pivot-mounted thirty-two-pounders, several six-pounders and swivels, and a rocket launcher made up her armament. And though she carried only half the crew of an 18-gun corvette like the Larne or the Modeste, she was almost their equal in tonnage — and in appearance, being half again as long, seemed actually larger.

As important as was the ship's combination of steam, windpower, iron, and a purpose built hull design was its captain and first second officers, all three from the Royal Navy:

Her commander was William Hall, a Royal Navy man past forty years of age who had received his master's warrant more than fifteen years before and had risen no higher. Hall had studied steam at Glasgow; he had made steamer passages across the Irish Sea and on the Hudson and Delaware rivers; as a very young man had accompanied the Amherst embassy to China. With him now went two other Royal Navy men as first and second officers. The rest of the officers and crew were civilian. The Nemesis was not commissioned under the articles of war. She was not listed with the ships of the East India Company's navy. She was to all appearances a private armed steamer. Hall was to take her around to the Indian Ocean and there receive his instructions, but even this much (oddly) was supposed to be secret. When the Nemesis sailed from Liverpool early in 1840, it was publicly intimated that she was bound for Odessa. . . . . "It is said," reported the Hampshire Telegraph, "that this vessel is provided with an Admiralty letter of license or letter of marque. If so, it can only be against the Chinese; and for the purpose of smuggling opium she is admirably adapted." [The Times, 30 March 1840] That was not far from the mark.

* To move the paddle wheels, 18 feet in diameter with floats 7 feet long, the Nemesis was equipped with 2 engines (one for each wheel) with 44-inch cylinders and a 4-foot stroke. Their estimated combined horsepower was a mere 120, by Hall's own confession not nearly enough.

Although carrying far fewer cannon than a frigate or even a corvette of the Royal Navy, Nemesis proved admirably suited to navigating the river mouths of China, which in those days were rendered impassable to ships of the line by virtue of mud flats and sand bars that accommodated only shallow draft vessels. She first saw action on 7 January 1841 when, having landed a force of 600 Sepoys of the 37th Regiment near the Chuenpi forts, Nemesis bombarded the city's watchtower while three seventy-fours remained on station off Boat Island. Whereas the Chinese gunnery proved inaccurate, every round from Nemesis found its mark, and the fortress fell shortly afterward. After serving as Britain's secret weapon in the first Opium War, Nemesis was last noted in Burmese waters in the early 1850s.

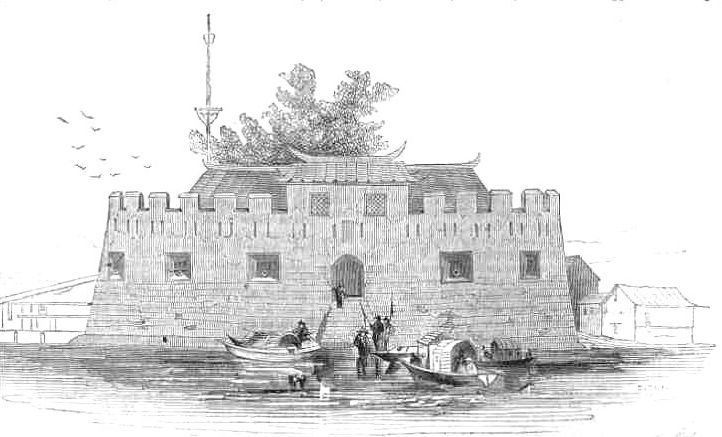

Left: Portrait of Sir Hugh Gough. Right: Chinese Fort. Click on images to enlarge them.

Her finest hour was undoubtedly in late May 1841 in the top of the Macao Passage when her maneuverability, steam power, and pivot-guns made her invincible against Chinese fire-boats and shore batteries. Her master's scouting a safe landing shortly thereafter enabled the British commander, Gough, to put his men where they needed to be to take Canton, upriver from the city. Thus, the British force had the remarkable luck of combining a redoubtable and highly adaptable vessel with a remarkably resourceful captain.

Bibliography

Fay, Peter Ward. The Opium War 1840-1842. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1975, pp. 260-63.

The Illustrated London News I (12 November 1842): 420.

Last modified 23 June 2006