n 1849, a clothing list for emigrants to New Zealand included "1 Horse-hair Petticoat"; and in 1852, settlers, when fairly well established, might hope to procure "Homebrewed Farmhouse Ale" or ale yeast in exchange for other "produce or firewood" (qtd. in Dawson 15 and 23). Ranging far more widely than the title suggests, Bee Dawson's Lady Painters is full of such surprises. It looks at seven women among New Zealand's early settlers, who, having come through the days of horsehair petticoats, and no longer directly dependent on the land for sustenance or refreshment, made names for themselves by depicting the islands' exotic flora.

While presenting examples of these artists' work, Dawson naturally explores the inspiration behind them — the exotic flora of the country in which the artists found themselves. She also looks at their training (if any), their materials and their reception. But her emphasis is on the women's individual experiences and circumstances, in what was still an entirely new and often very challenging world. Penelope Hobhouse is right to prepare us in her foreword for an art-book that is also, or even primarily, "an illuminating social history which teaches us about commonplace living in raw New Zealand" (ix).

Dawson's first example, Martha King (c.1803-1897), was an Irish immigrant from the family of a Protestant clergyman, who took ship for New Zealand in 1840 along with her older brother Samuel and sister Maria, probably in order to escape the harsh conditions of early Victorian Ireland — maybe also, since she and her sister were now in her later thirties, to improve her chance of marriage. The three siblings bought land in Wanganui, farther north from Wellington on the west coast of the North Island, and later moved to New Plymouth, higher up the coast. There were struggles and setbacks, including land disputes, factions among the settlers themselves, and the loss of their possessions, which were following them, in a shipwreck. But they were well-educated, cultured people, and before too long became pillars of the local community. Schoolteaching alongside her sister, and already recognised for her skill as an artist, Martha supplemented the Kings' income with commissioned work, and the family (which now included Samuel's younger wife Mary, who taught music) were able to live in some style, holding balls in their schoolroom and generally enjoying a high status in New Plymouth society.

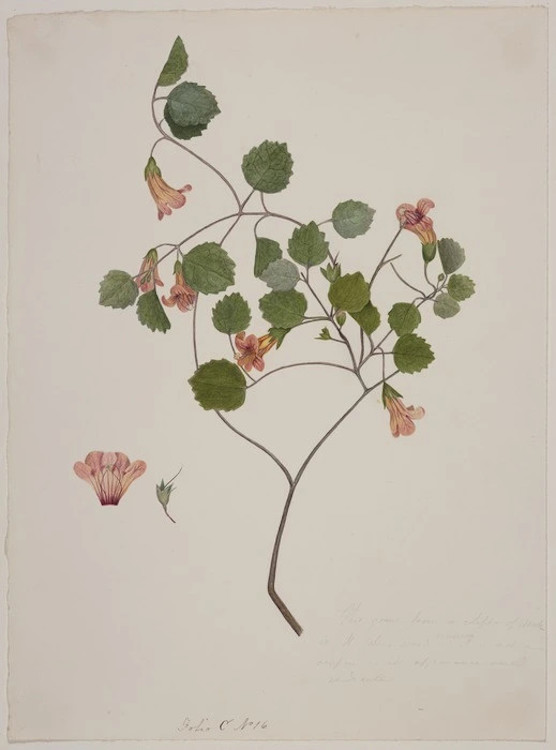

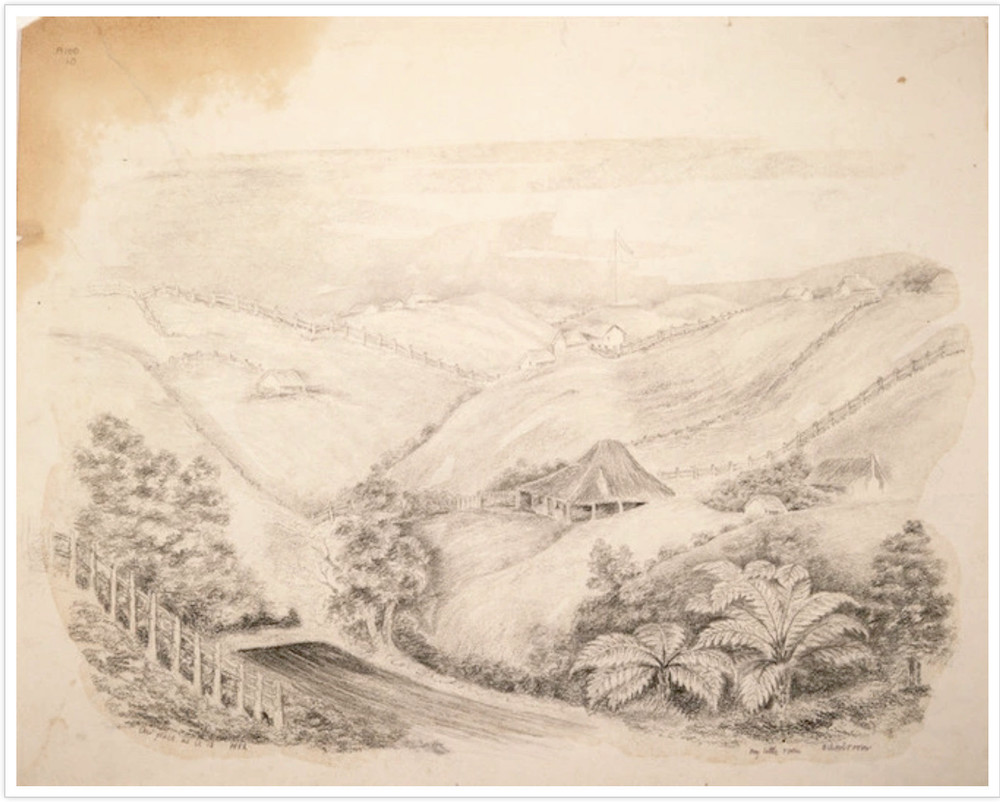

Two images of King's work in the collection of the Alexander Turnbull Library, with comments from the Library's notes. Left: her watercolour on paper of New Zealand's native gloxinia, found in a "cleft of rock" and "[p]repared for the New Zealand Company in 1842," 375 x 276 mm. Ref. A-005-016. Right: Pencil drawing of "Our place as it is 1852": "Behind the King house, is a small shed marked as 'my little room' and a larger cottage marked as 'school room'." 237 x 294 mm. Ref. A-100-010.

Not that everything was plain sailing. In 1860, during the New Zealand wars, the family had to evacuate to Auckland for a while. But they were soon re-installed, and by the end of 1862 Martha was in a position to give up her teaching. Now, "as much a keen plantswoman as an artist" (27) she could spend more time on her gardening, and before she died in 1897, at the ripe old age of 94, directed that her estate should be used for a public garden for the enjoyment of the whole community in New Plymouth. Her art, featuring exotic flowers seen with fresh eyes, and depicted with loving care as well as scientific accuracy, would be her other legacy.

Another story of success wrung out of difficulties was that of Dawson's next "lady flower painter," Emily Cumming Harris (c.1837-1925). Emily was probably too young to remember pitching tent in the new land, as the Kings had once done. She was brought out with her family towards the end of 1840, swapping her toddler years in Plymouth on the south coast of England for childhood in the same area as Martha, New Plymouth. Yet she too would soon become aware of the precariousness of settler life. The Harrises' first home burned down a few weeks after they became established there, and, like Martha and her siblings, they suffered during the fighting of 1860. Indeed, Emily lost her older brother to the hostilities. Still, there were useful developments by now, especially for a would-be artist: before resettling with her remaining family in Nelson, in the South Island, she had the chance of a formal education in art in Hobart and then Melbourne. Subsequently, she was able to arrange some local exhibitions and to show her work twice in Melbourne, and also in London at the 1886 Indian and Colonial Exhibition. She published three books of lithographs as well. These were then collected into one large volume, and, in a separate and quite different project, but still one that evoked a sense of wonder in artist and viewer alike, she illustrated a book of fairytales.

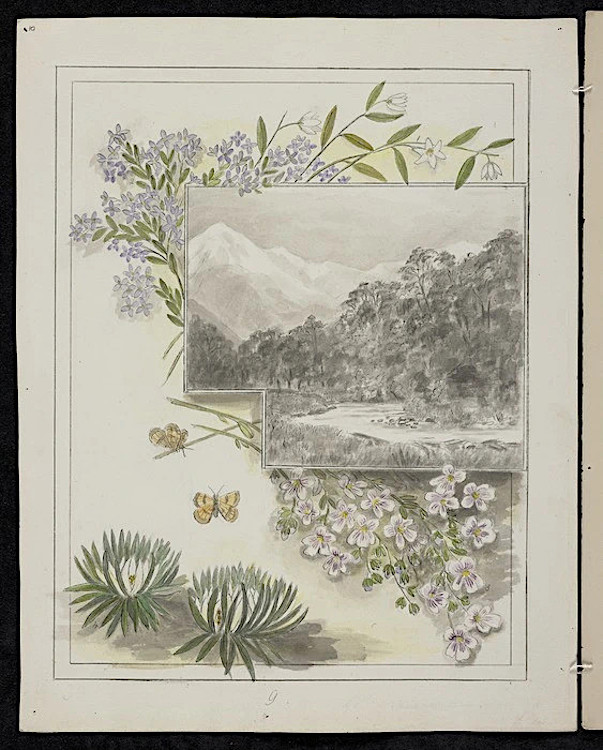

Emily Harris's arrangement of several species in their landscape, ink and watercolour, 265 x 205 mm, from New Zealand Mountain Flora, in the Alexander Turnbull Library collection, ref. E-001-q-010.

Even if Emily often lamented the little time she had to devote to her painting, and the little financial reward it brought her, she certainly became "a successful artist in colonial terms" (40), and won some gratifying and surely well deserved critical acclaim, particularly for an unpublished collection showing alpine plants in their context.

By choice, the parents of another "lady painter," Fanny Osborne (1852-1933), lived much more remotely than either the Kings or the Harrises. Disappointed after losing much of his inheritance, and sharing his fellow-immigrants' hope for better luck with a fresh start, her Scottish father had come out with his wife Emilie, and the couple had raised their large family on the Great Barrier Island off the east coast of the North Island. Somehow, but as with others among these energetic and determined settlers, they maintained their standards, providing a good level of (in this case) home-schooling, and fostering the little ones' abilities. But Fanny had none of Emily's advantages. Her "only tutors were her mother and nature itself," says Dawson (50). Rather than going to any art school, and against her parents' will, Fanny married one of the later immigrants there — seen almost as invaders at the time — and produced her own brood of thirteen childen. Inevitably, it was years before she could find time for her easel, so Fanny won a reputation for herself only later in life. Here Dawson includes a useful discussion of her materials, whether painstakingly mixed at home or sourced from Auckland, as well as the preservation of her work, some of it understandably faded and foxed. It is heartening to read that she passed on her skills to several of her children.

Fanny Osborne's Native berries of New Zealand, printed by the Brett Printing Company [1913], in the Alexander Turnbull Library collection, ref. C-066-007.

However, Dawson tells, the "first fully-coloured art book to be printed in New Zealand" was not Fanny Osborne's, but Sarah Featon's (74). The Art Album of New Zealand Flora, being a systematic and popular description of the flowering plants of New Zealand and the adjacent islands, was published in three parts, 1887-88, and as one volume in the following year. Such was its cachet that a copy of the sumptuous book was sent to England in a beautifully handcrafted casket, and presented to Queen Victoria on the occasion of her Diamond Jubilee in 1897. Not all of Dawson's subjects left much of a paper trail behind them, and there is more speculation here, in the chapter on the "frustratingly elusive" Sarah Featon (1848-1927), than in other chapters. Consequently there is a wealth of general information here about about hairstyles, costume and so on, and the kind of life Sarah and her husband would have lived in Gisborne, on the east coast of the North Island — a recent settlement with, at first, a population of a mere 500 hardy souls. "Frontier territory" (64) when they arrived, it was subject to volcanic eruption, and had no mail service until the late 1870s, depending even then on a fortnightly mail-steamer to Auckland. Yet out of these circumstances came Sarah's delicate and responsive artwork. Her husband Edward, a military man in receipt of the New Zealand war medal for service in Tauranga, had a special fondness for literature and art, and wrote the text for this celebrated work.

Sarah Featon's Yellow kowhai, Sophora Tetreptera, from the celebrated Art Album, Bock & Cousins Lithographers. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, reference: PUBL-0025-28.

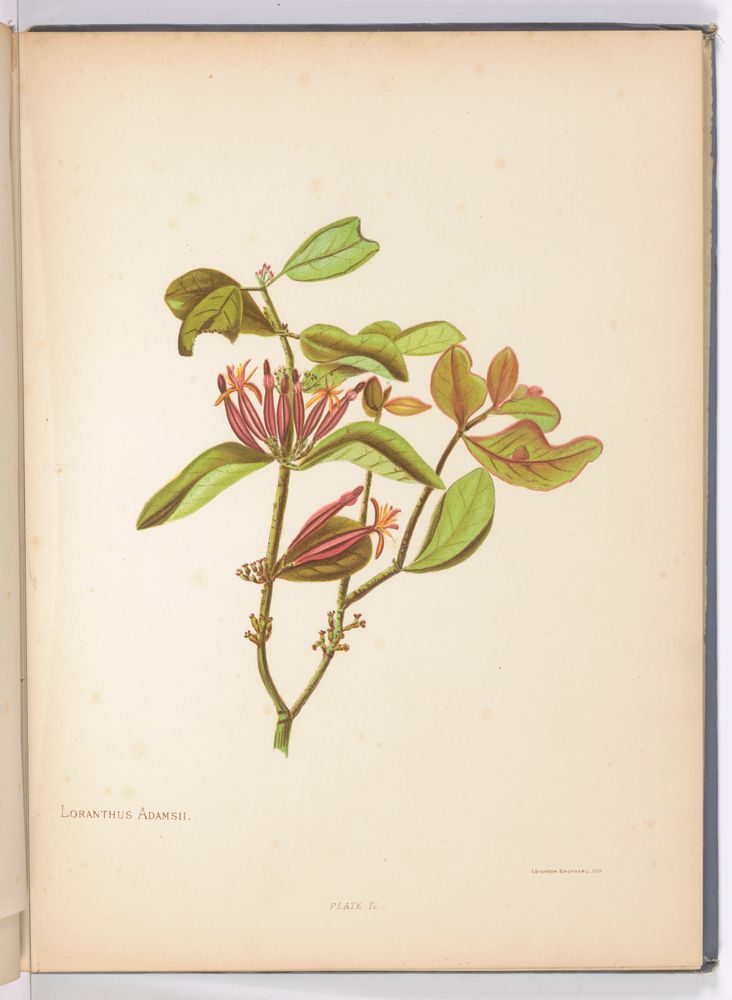

Of the other resident artists featured by Dawson, probably the most important was Georgina Hetley (1832-1898), who knew Sarah, and whose own book on New Zealand's native flowers came out almost at the same time as hers, but was published in England. This was actually dedicated to Queen Victoria, but Dawson suggests that its publication abroad somehow takes away from its status as a "landmark" work for her home country (79). This seems unfair: like Martha King and Emily Harris, Georgina had lived through the land wars in the New Plymouth area, and in the early 1880s joined the New Zealand Art Students' Association, the aim of which was to develop art distinctive of the country. She subsequently went on tour with the New Zealand botanist, Thomas Cheeseman (1845-1923), enduring various risks and hardships, and often bewailing the burning of forests for land clearance, as she captured the unique plant life around her. In one case at least, she was able to depict a species (the native mistletoe) before it became extinct. Her book's publication in England came out of her special trip there to seek a publisher. She was able to visit the Colonial and Indian Exhibition, as well as (by invitation) do some work at Kew. Her recognition in the "old country" was a landmark of a different kind from Sarah's.

Left: Georgina Hetley's The Native flowers of New Zealand: illustrated in colours in the best style of modern chromo-litho art, from drawings coloured to nature, lithographed by the Leighton Brothers (John and Henry), and published in London by Sampson Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington Ltd., 1888). Gift of New Zealand Parliamentary Library, 2024. Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa (RB001577). Right: Loranthus Adamsii, the native mistletoe which became extinct. Plate 12 from the book. Images described as having no known copyright restrictions.

But the age of botanical discovery was gradually passing, the sense of wonder at an exotic new land was fading, and imported English flowers were becoming not only readily available in New Zealand, but in much demand. In short, the pioneer days were over. Next, Dawson looks at the fashionable Isabel Hodgkins, later Field (1857-1950), whose father had worked at the National Portrait Gallery before emigrating, and who became a major figure in Dunedin's art world on the South Island. Her sister Frances was the more truly committed artist; painting was largely a hobby for Isabel. She worked in different genres, but is represented here by (among others) a study of a vase with a floral design, and another one of a vase of pink flowers. For Margaret Stoddart (1865-1934) too, the last of Dawson's resident artists, beautiful flowers were still-life subjects rather than objects of scientific interest. Coming from Christchurch on the south-eastern coast of the South Island, she and her sisters were enrolled at the region's newly opened Canterbury College School of Art, and Margaret went on to become highly regarded abroad as well as in New Zealand, spending over nine years in England and Europe, living in St Ives for a while among the artists there, and exhibiting several times at the Royal Academy and elsewhere. Still, it was on her return to New Zealand, after about nine years abroad, that she achieved her greatest success and influence, with views of the landscape around her in the Canterbury area again. Keeping up with modern trends, her flower-painting too had become increasingly impressionistic, a far cry from the precise correctness of her predecessors.

Roses, c.1930, Christchurch, by Margaret Stoddart. Gift of the New Zealand Academy of Fine Arts, 1936. Museum of New Zealand/Te Papa Tongarewa (1936-0012-255). Image described as having no known copyright restrictions.

Margaret's involvement in the Canterbury art community of her time indicates that there was a whole other book to be written here, about the institutions that had now grown up in New Zealand to foster and display artistic talent. An index and a bibliography would have helped readers to draw all the strands together to make their own picture of this evolving culture. However, Dawson stays true to her own aims, to shed light on each artist's own personal growth. She ends by examining a couple of visiting artists, one of them the best-known name in the book — Marianne North, who came to New Zealand in early 1881 when she was really too poorly to enjoy her stay, but took pleasure in such striking botanical curiosities as flax-bushes, with "black shiny seeds most exquisitely packed in grooves in the pods" (140). There were still many such wonders, even if those who had grown up amongst them were now less struck by them. Another visitor, this time from Australia, was Ellis Rowan (1848-1922), who had already won an impressive number of medals at various international exhibitions, and who lived in New Zealand for a while with her army officer husband, Captain Frederic Rowan. She seems to have found botanical painting trips a welcome escape from domestic life. An admirer of Marianne's work, she too painted less strictly as a botanist: indeed, her husband himself urged her to "get the detail right" (qtd. p. 127). But the time flower art was no longer so directly representational. Like Marianne North, she achieved success without absolute fidelity, on her own terms.

This is a most enjoyable book, giving many insights into New Zealand's early settlement. In a way, the new arrivals were bringing in their own culture, some of the artistically inclined women painting wildflowers just as many of their counterparts were doing in the countryside they had left behind them. But these more adventurous women were responding to different species, and opening the eyes of their new communities to new wonders. As the years went by, botanical description was subsumed or, rather, blossomed into memorable artwork, which won acclaim far beyond their Pacific shores. To their credit, too, the passage of time brought new concerns, like Georgina Hetley's, for the preservation of species; and a new appreciation, like Sarah Featon's, of the indigenous culture.

Further Reading

Many thanks to Pamela Gerrish Nunn for these suggestions:

Blackley, Roger. Galleries of Maoriland: Arists, Collectors and the Maori World, 1880-1910. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2019 (about the formation of museum collections in New Zealand).

Porter, Frances. Born to New Zealand: A Biography of Jane Maria Atkinson. Wellington, N.Z.: Allen & Unwin: Port Nicholson Press, 1989 (about one of the most fascinating settler families who made their mark in a variety of ways).

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Dawson, Bee. Lady Painters: The Flower Painters of Early New Zealand. Auckland, NZ: Viking, 1999. 144 + xi pp. ISBN 0 670 88651 3

Created 16 August 2025