Left: St Thomas’s Cathedral. Bombay (Mumbai). Right: Monument to the crew of the “Cleopatra”. J. Bovey. Detail: the inscription of the sculptor's name [Click on images to enlarge them.]

A memorial in St Thomas’s Cathedral Bombay (Mumbai) commemorates the loss of the East India Company’s steam frigate Cleopatra along with 9 officers and 142 crew. No mention is made of the one hundred Indian convicts who also died. They were all victims of the great hurricane of 15th April 1847.

The Asiatic Journal for 1839 records that

The East-India Company are fitting out three steam-vessels of war for the protection of trade in the East against pirates, and for any other emergencies. They are about 800 tons each. The Queen, intended for Bengal, was built at the same yard whence the British Queen was launched, and the President, her rival, is building the Cleopatra and Sesostris at Northfleet. The two former have round, and the latter a square stem and will be armed with very heavy metal.

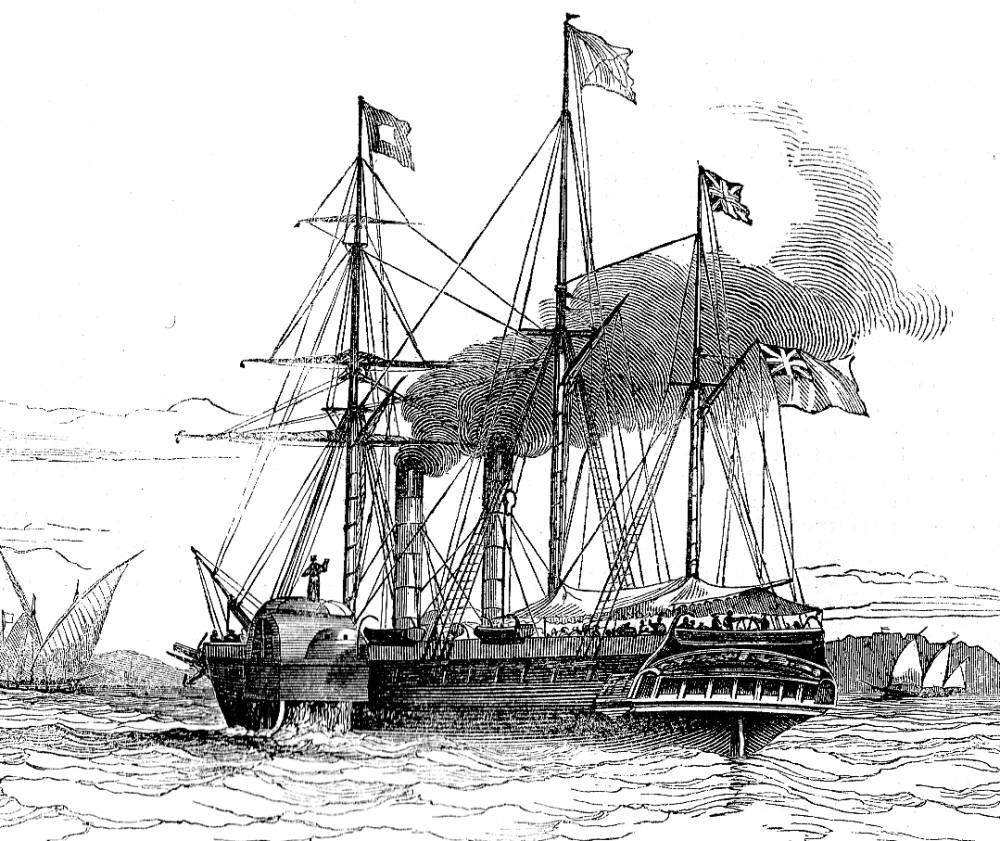

A similar vessel — a detail in a wood-engraving in The Illustrated London News (6 July 1844): 8. Click on the image for the full caption and complete image.

The Cleopatra was a wooden paddle sloop built by Pitcher of Northfleet, launched in 1839. She was 178ft 5in long, 31ft wide and 760 tons. Her steam powered engine was rated at 220nhp. The Asiatic Journal of 1840 records that “The Cleopatra, steamer, [commanded by Lieut] Saunders, from London to Bombay put into Lisbon 9th December, having lost her foremast, sails, &c, four days previous. She had experienced very bad weather after sailing from Portsmouth, and was expected to remain at Lisbon three weeks”. She finally reached Bombay in April 1840.

In spite of the East India Company’s original intentions, Cleopatra was mainly employed in ferrying mail between Bombay, Karachi, Aden and Suez; part of the system which was gradually improving communications between London and India via Marseilles or Malta and Alexandria followed the overland route to Suez (the Suez Canal would not be completed until 1869) and thence via Aden to Bombay. An article in the Illustrated London News of 6th July 1844 waxes lyrical about the wonders of the new mail system. “We have described in former numbers the course of the Indian Mail from Bombay to Marseilles ... since that period the subject has grown to be one of greater importance; the States of Hindustan have become more essential to the welfare of the home country: China has been added to our commercial empire; and the course of trading adventure on the coasts of Burmah, Japan and many wondrous places of the Orient seas have combined to give all Post Office arrangements with these immense territories a degree of surpassing interest. The flight of the Indian Mail is in truth a wonder of the day.”

For the tragic demise of the Cleopatra I must turn to Charles Rathbone Low’s authoritative History of the Indian Navy:

In April, 1847, the Cleopatra was placed under orders to convey one hundred convicts to Singapore, although, when making the passage from Bombay to Aden in the voyage immediately preceding her last, she had worked together to such an extent that Commander Young had actually to secure her paddle-boxes by chains thrown across the decks and fastened on either side.

This he officially reported on his return. The condition of the ship being so unsatisfactory, Commander Young proceeded to the office of the Superintendent and remonstrated with him against sending a ship to battle against the approaching south-west monsoon in a notoriously unfit condition. Sir Robert Oliver, who was at no time remarkable for the possession of an amiable temper, was furious at a subordinate officer attempting to remonstrate, no matter how respectfully, against his orders, and he turned upon the noble seaman before him, whose whole life had been characterized by unselfish devotion to duty, with a bitter taunt that he was deficient in nerve. Commander Young made no reply, but went on board his ship, which sailed from Bombay on the 14th of April, and from that day no word was ever heard more of the Cleopatra .

The ill-fated ship had scarcely cleared the coast than one of the most terrible cyclones on record, swept over the Indian Ocean, and, it is supposed, engulfed the Cleopatra and the gallant hearts on board her. We would not say that the loss of the Cleopatra and the valuable lives on board her, is to be laid at Sir Robert Oliver's door, for it is probable that the stoutest ship would have succumbed to the cyclone had she been caught in its vortex; but, equally, we cannot acquit the Superintendent of serious wrong in disregarding the remonstrances of the Captain of the Cleopatra which might have battled through that terrible ordeal had she been made perfectly seaworthy.

No special search was at this time made for the Cleopatra, and the Coote returned to Bombay; but, as time wore on, and no news was received of her arrival at Singapore, anxious fears began to be whispered about, and, at length, on the 28th of August, Lieutenant John Wellington Young [the brother of Captain Young] was despatched to the Laccadive Islands [off the coast of modern-day Kerala] in the Auckland. It was all to no purpose, and the sickening dread of the worst was soon confirmed in the breast of the gallant commander of the Auckland.

The ship's company of the Cleopatra numbered one hundred and fifty-one souls, and, in addition, there were on board, for passage to Singapore, one hundred convicts, with a strong marine guard, under charge of Mr. Anderson, Chief Constable of the port; so that probably there were nearly three hundred souls on board the Cleopatra when she foundered in mid ocean. A monument, executed in white marble, by Mr. Bovey, of Plymouth, was erected, in Bombay Cathedral, to the memory of the officers and crew of the ill-fated ship. The design is simple and appropriate. ”

Indian convicts in Singapore

No mention is made on the memorial of the convicts on board. Vernon Cornelius-Takahama, an historian of Indian convicts in Singapore, explained that many Indian convicts ended up there because it had a “labour shortage” aggravated by the rapid growth of this trans-shipment port. The British first began to transport convicts to Australia in 1787, and the following year the authorities in India began to send their convicted felons to Sumatra. A year later (1790) the first convicts were sent from India to Penang, in what is now Malaysia. “From 1825, Malacca and Singapore also became convict stations. By 1841, the Straits Settlements became the "the Sydney convict settlements of British India", and there were between 1,100 and 1,200 of these convicts in Singapore alone. In 1845, the numbers had risen to 1,500. A Free Press newspaper report on 22 July 1847 confirmed the numbers of 1,500 Indian convicts in Singapore. . . . Laying many of Singapore's early public roads, erecting monumental buildings and bridges, these convicts literally built early Singapore.”

Unfortunately, the 100 convicts on the Cleopatra never made it to Singapore.

Further reading.

Asiatic Journal for 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. London. W.H. Allen.

Illustrated London News. 6th July 1844 Page 8.

Cornelius-Takahama, Vernon. Indian convicts' contributions to early Singapore. National Library Board, Singapore. 2001.

Low, Charles Rathbone. History of the Indian Navy. 1613-1863. London: Richard Bentley, 1877.

Last modified 13 October 2016