In transcribing the following paragraphs from the Internet Archive online version of The Imperial Gazetteer’s entry on Egypt I have divided the long entry into separate documents, expanded abbreviations for easier reading, and added paragraphing and links to material in the Victorian Web. Unless otherwise noted, charts and illustrations come from the original Gazetteer. — George P. Landow

he general rocks of Egypt are limestone, sandstone overlying the former, and granite, which breaks through and overspreads both. The granite region lies at the South extremity of Egypt. In Lower Nubia, the summits of the granitic rocks rise 1000 feet above the level of the river. This rude and wild scenery continues down to Assouan, where the cataracts are formed by the cliffs and broken masses of granite which lie in the bed of the river. Granite of many varieties may be found here; but the rock at Assouan or Syene is not the syenite of modern geologists. Blackened by the sun’s rays, and often highly polished, these rocks have been frequently mistaken for basalt; and, indeed, it is not cer tain that truly volcanic rocks may not be found mingled with the granite.

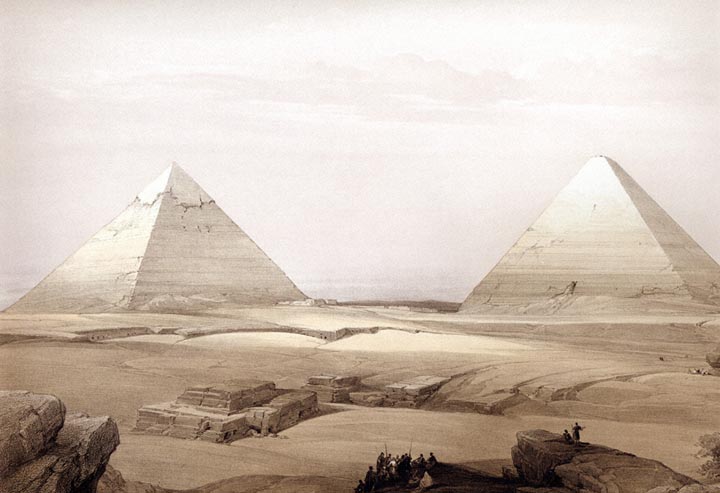

The cliffs near Assouan have supplied the materials for all the colossal and monolithic monuments of Egypt. From Assouan to Esne" (latitude 25˚ 19" North) extends the sandstone formation, which is very durable, and easily worked. The quarries at Jebel Silsilis (chain mountain), and a few other points in this region, furnished the materials for the superb structures of Thebes, and, indeed, for most of the temples of ancient Egypt. Below Esne the limestone predominates, though sandstone hills still occasionally interrupt the cal careous range. The limestone region is more tame and monotonous in outline than those of the sandstone and granite, and more frequently affects the form of table lands. Thus the pyramids of Gizeh, built altogether of limestone, stand on an elevated plain of the same material.

Pyramids of Geezeh by David Roberts, R.A. Signed with the name of the artist and lithographer, Louis Haghe. From Eygpt and Nubia, 1842. Click on images to enlarge them.

The Egyptian lime stone is generally grey, containing fish, shells, and corals; but in the East desert, specimens have been found of handsome marble; and in the parallel of Minyeh, latitude 28˚ 4' North, and about 100 miles East of the Nile, were discovered, a few years ago, the splendid ruins of the ancient Alabastropolis, which once derived wealth from its quarries of alabaster. Farther South in the desert, towards the limits of the granite, we come upon the ancient mines or quarries of jasper, porphyry, and very antique.

The emerald mines of Zebarah lay near the Red Sea, in the parallel of Syene. To complete this brief geological sketch, it may be mentioned that in the calcareous region, diluvial heaps of oyster and other shells frequently occur at considerable elevations, and that a few miles East of Cairo, in the Jebel Mokattem, an extensive tract is strewed over with the silicified trunks of trees. This phenomenon of a petrified forest presents itself again in the desert of the Natron Lakes, West of the Nile, and also far to the South in Nubia.

Alluviumiles

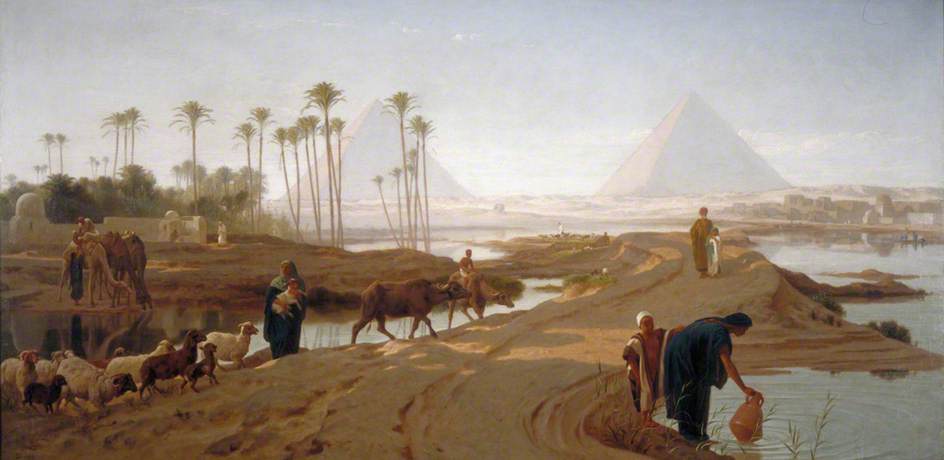

he alluvial soil of Egypt is a no less interest ing object of study than the rocky foundation on which it rests. The Nile, during the floods, deposits in the valley of Egypt the earthy particles with which it becomes loaded in the early and impetuous part of its course, and it is easy to recognize, in the dark brown mould of Egypt, the disintegrated trachytes of Abyssinia. Wherever the velocity of the stream is checked, the earthy sediment is deposited, and a thin, slimy film spreads over the ground. The accumulation of this fine sediment becomes very perceptible in the course of ages, the inundated land of Egypt, with the bed of the river, being gradually raised by means of it. The increase of the soil is said to proceed, in Upper Egypt, at the rate of 4 or 5 inches in the century; in the Delta it goes on more slowly.

The Subsiding of the Nile, Egypt. 1873. by Frederick Goodall. Reproduced by kind permission of the Guildhall Gallery, London, and the City of London Corporation.

The banks of the Nile, as they first check the current, receive the largest share of the deposited soil, and hence they are higher than the adjacent fields, which also generally decline a little from the river. The lower part of the nilometer at Elephantine, or standard for measuring the rise of the waters, described by Strabo, still remains entire; but the highest graven Hue on it is now covered to a height of 8 feet by the flood.

Statues of Memnon at Thebes, during the Inundation b by David Roberts, R.A. Signed with the name of the artist and lithographer, Louis Haghe. From Eygpt and Nubia, 1842.

From the depth of the sedimentary soil covering causeways or heaped round monuments at Thebes, which doubtless stood originally above the reach of the inundation, it has been calculated that the age of that city must reach back at least to the year 2960 B.C., a conclusion which can be reconciled with the chronology of Scripture only by adopting the Septuagint or Samaritan text in preference to the Hebrew. Thus it appears that the Greeks were, in some measure, justified in saying that Egypt is the gift of the Nile; but they alluded more particularly to the Delta, and yet it is evident that the Delta has advanced but partially, between the two main branches, and only a distance of 3 or 4 miles within the period of history. Its coast on the West side, including Alexandria, and as far East as Abukir, is formed by a ledge of limestone, and cannot be supposed to have undergone any change. On the East Tineh, one of the most ancient of Egyptian cities, still occupies the site of Pelusium (the Sin of Ezekiel); and still on the sea-shore, it fully merits its ancient names, which all had but one meaning mud. It is, however, conceivable that before the industry of man insisted on controlling and regulating, by means of dykes and canals, the effects of the inundation of the Nile, the deposition of alluvium at its mouth gained rapidly on the sea. [2.908-09]

Bibliography

Blackie, Walker Graham. The Imperial Gazetteer: A General Dictionary of Geography, Physical, Political, Statistical and Descriptive. 4 vols. London: Blackie & Son, 1856. Internet Archive. Inline version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 31 July 2020.

Last modified 1 August 2020