This document has been shared, most graciously, with the Victorian Web by David Stewart of Hillsdale College, Michigan; it has been taken from the College's website. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr. Stewart.-- Marjie Bloy Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, National University of Singapore.

Bivouac, River Alma, 21 September 1854

I hasten to write a few lines to tell you I am safe and sound, knowing how anxious you will be, after hearing that we have had an action with the Russians.

Accounts of the battle you will see in the papers, much better describing it than any I could give, as I could see nothing beyond what was going on in my own brigade. That you will see was in the thickest of it, as the returns of our casualties will prove, our loss being very severe. The march from Kamischli to Baljanik, where we bivouacked on the night of the 19th, and again from Baljanik to Alma, was the grandest spectacle I ever saw. The whole Army, French, English, and Turkish, advanced in battle array for that distance over a plain as smooth almost as a lawn, and with just sufficient undulation to shew one at times the whole force at a coup d'oeil. My division was on the left, and we were about three miles from the sea; the fleet, coasting along abreast of us, completed the picture.

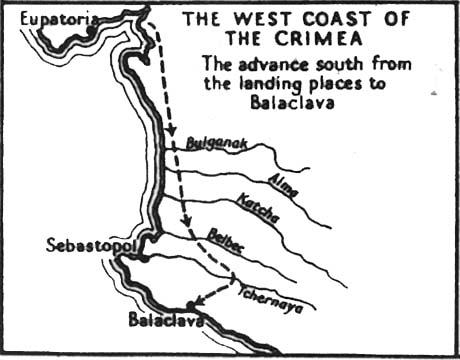

Left to right: (a) The allied route to Sevastopol This map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's The Destruction of Lord Raglan (Longmans, 1961), p. 10, with the author's kind permission. Copyright, of course, remains with Dr Hibbert. (b) Victory of the Alma from Punch. (c) The Late Marshall St. Arnaud, Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Armies. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

At about 12 o'clock on the 20th, on crowning a ridge, we came all at once in sight of the Russian army, in an entrenched camp beyond the Alma, distant about three miles. Immediately we appeared they set fire to a village between us and them so as to mask their force by the smoke.

We continued advancing steadily, halting occasionally to rest the men, till half-past one, when the first shot was fired, and soon after the rattle of musketry told us that our rifle skirmishers were engaged. Our division then deployed into line, and we stood so for about twenty minutes, an occasional round shot rolling up to us, but so spent that one was able to step aside from it. Wounded men from the front soon began to be carried through our lines to the rear, and loose and wounded horses began to gallop about.

At last we were ordered to advance, which we did for about 300 yards nearer the batteries, and halted, and the men lay down. We were now well within range, and the round shot fell tolerably thick, an occasional shell bursting over our heads.

After standing steady for about twenty minutes, the light division (who were in line in front of us) advanced again, and we followed.

The Russians had put posts to mark the ranges, which they had got with great accuracy. We now advanced to within 200 yards of the river and 700 from the batteries, and halted under a low wall for five minutes, till we saw the light division over the river, when we continued our advance in support of them. On crossing the wall we came into vineyards, and here the cannonade was most terrific, the grape and canister falling around us like hail — the flash of each gun being instantly followed by the splash of grape among the tilled ground like a handful of gravel thrown into a pool.

On reaching the river, the fire from a large body of riflemen was added, but the men dashed through, up to their middle in water, and halted on the opposite side to re-form their ranks, under shelter of a high bank. At this moment the light division had gained the intrenchment, and the British colour was planted in the fort; but, ammunition failing them, they were forced back.

The Scots Fusiliers were hurried on to support them before they had time to reform themselves, and the 23rd, retiring in some confusion upon them, threw them for a few minutes into utter disorder. The Russians, perceiving this, dashed out of the fort upon them, and a frightful struggle took place which ended in their total discomfiture.

For a minute or two the Scots Fusilier colours stood alone in the front, while General Bentinck rallied the men to them, their officers leading them on gallantly.

At this moment I rode off to the Coldstream, through whose ranks the light division had retired, leaving them the front line. They advanced up the hill splendidly, with the Highlanders on their left, and not a shot did they fire till within 150 or 200 yards from the intrenchments. A battery of 18 and 24 pounders was in position in our front, and a swarm of riflemen behind them. Fortunately the enemy's fire was much too high, passing close over our heads, the men who were killed being all hit on the crown of the head, and the Coldstream actually lost none. When we got about fifty yards from the intrenchment, the enemy turned tail, leaving us masters of the battery and the day.

As they retired they took all their guns except two, and a great many of their wounded. In spite of this the ground was covered with dead and dying, lying in heaps in every direction on what might be called the glacis, and inside the intrenchments they were so thick that one could hardly avoid riding over them; but the excitement of the victory stifled for the time all feeling of horror for such a scene, and it was not till this morning when I visited the battle-field, that I could at all realise the horrors which must be the price of such a day. Most fervently did I thank God, who had preserved me amidst such dangers. How I escaped seems to me the more marvellous the more I think of it. Though on horseback (on my old charger), my cocked-hat and clothes were sprinkled all over with blood.

The loss of the Brigade of Guards is very severe, but the proportion of deaths to wounded is extraordinarily small. On calling the roll after the action, 312 rank and file and fifteen officers were discovered to be killed and wounded.

Besides there was my poor friend Horace Cust, who was struck by a round shot in crossing the river. He was aide-de-camp to General Bentinck, and we were watering our horses at the time when the shot struck his horse in the shoulder and smashed poor Cust's thigh. He died soon after the leg was amputated. Charles Baring, who has lost his arm (taken out of the socket) is the only other Coldstream officer hit. They only went into action with sixteen officers, less than half their complement.

We have been occupied the whole day in burying the dead. About 1000 were laid in the ditch of the fort, and the earthen parapet was then thrown back upon them. We find that the whole garrison of Sebastopol were before us, under Mentschikoff in person. His carriage has fallen into our hands, and in it a letter stating that Sebastopol could hold out a long time against us, but that there was a position at Alma which could hold out three weeks. We took it in three hours.

So convinced were they of the impossibility of our taking it that ladies were actually there as spectators, little expecting the review they were destined to be spectators of. We expect now to find no resistance whatever at the Katcha river, the whole Russian force having retired into Sebastopol. We always turn out at four o'clock in the morning, an hour before daybreak.

Other accounts of the Battle of the Alma

- Lieutenant-Colonel Calthorpe's account

- Timothy Gowing's account

- Lord George Paget's account

- WP Richards' account

- Charles Usher's account

Related Material

Last modified 13 May 2014