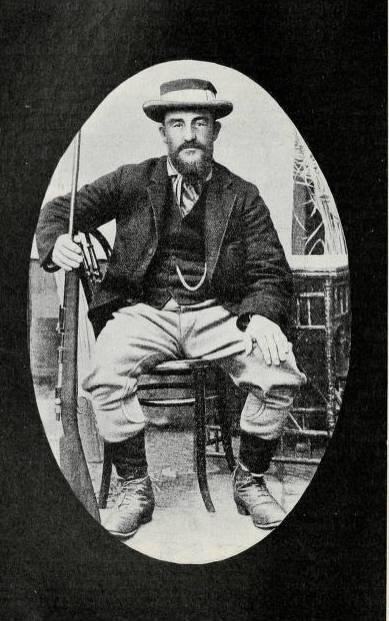

Chief Commandant General Christian De Wet

Photograph

Source: Rompel’s Heroes of the Boer War, 128.

“Oom Chrisjan first made his mark at Blauwbank, on the 15th of February 1900. News had come that the English were marching from the South in the direction of Koffijfontein. Cronje thought that they meant to enter the Free State by Koffijfontein, and sent De Wet, with his own brother, Commandant Andries Cronje, to Blauwbankto repel the invasion. Here De Wet captured the enemy's huge convoy, and, as often happens when an officer takes suddenly a fine prize, established his reputation. Everyone talked of De Wet and even, for a moment, forgot the defeat of Cronje, who had, on the same day, 15 February 1900, evacuated the Magersfontein position, and the news that had come to band of the relief of Kimberley.” [continued below]

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Internet Archive and the University of California Library and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.

Oom Chrisjan showed his burghers at Blauwbank that he was no easy man to deal with. He drove them back to their trenches with his whip when they attempted to fly, and they became so afraid of their angry general that they no longer dared retire.

Three days later, he arrived with his commandoes at Paardenberg, where Cronje was hemmed in by the English. His fame preceded him:

"De Wet is coming!"

And this shows the influence of a name. It was as though the burghers had suddenly been imbued with fresh spirit. They had lost courage latterly owing to all their reverses: but De Wet would put everything right again. On that 18th of February, all the commandoes fought bravely; but Cronje again was stubborn. He refused to leave the women and children and his baggage behind and to cut his way through the British lines. De Wet, who was now in command, was constantly contriving new plans to release Cronje. But the numerical superiority of the enemy was too overwhelming. Still he did not lose courage.

I distinctly remember the 23rd of February 1900. De Wet had planned a general assault. It was a daring scheme. All the mounted commandoes were simultaneously to storm the British positions. Oom Chrisjan stood with his staff on a kopje, whence he could command the whole field. He saw the burghers gallop bravely to within rifleshot of the positions. Then came the rattle of rifle-fire. The men advanced, but were compelled to fall back. They did not see the enemy, did not know where nor in which direction to fire. The brave Winburghers were swallowed up in the enemy's wedge-shaped position. The Lee-Metfords cracked from three sides. The Winburghers had to surrender. There was no other escape from death. We on the kopje saw this. It was a tragic spectacle. De Wet said not a word. He only compressed his lips tightly together, and his features assumed that biting aspect which I have found again in his later portraits. It was a resolute man that stood that morning on the kopje. But tears gleamed in his eyes.

In the early morning of the 27th of February, I learnt from some Kaffirs that Cronjé had surrendered. They came from his laager, where the English had let them go free. I refused to believe the fatal news, saddled my horse, and rode over to De Wet. I found the general silent, and introspective as usual, and asked him if he had received any confirmation of the report. He too had heard it, but did not believe it. And lie told me this with something grim and resolute in voice, look and bearing, as though he meant to say, "Come what may, it will make no difference to my resistance".

Poplar Grove (7 March 1900) and Driefontein (10 March 1900) were not successes for De Wet. They showed that his strength did not lie in the grande guerre. At Poplar Grove he was warned in time by his scouts of the encircling movement of the enemy. He did not strengthen his flanks. True, it would not have availed him against the superior forces; but to neglect the precaution was a mistake.

Two days later, he defended the approach to Bloemfontein with 600 men. What could he do, however, against Lord Roberts' army? But it was a point of honour with him not to give up the capital without striking a blow in its defence. The other officers had wished to do so, but not he. He was too grimly determined to contest every inch of territory against the enemy.

And, in the evening, when he left Bloemfontein, knowing that, the next morning, the English would make their unimpeded entry, he assured his friends that he would return one day when the Free State was free again. This was no bluster, but a sacred promise, uttered in deadly earnest. The words, so calmly spoken, gave fresh courage to his officers. De Wet's determination was contagious.

From that day his epoch of fame begins. The victories of Sanna's Post (1 April 1900) and Reddersburg (5 April 1900) bade the fighting Boers be of good cheer. De Wet hovered around Bloemfontein. He cut off the Water Works and held them in his possession until Lord Roberts began to march to Pretoria (3 May 1900). He spoilt the British joy at the occupation of Johannesburg by his victory over the 13th Battalion of Imperial Yeomanry at Lindley (31 May 1900). He embittered the delight at the surrender of Pretoria on the 5th of June by capturing a large train of supplies at Honingspruit on the 6th and surprising the Derbyshires on the 7th.

De Wet had developed into the man he was thenceforward to show himself, the general whose talents compelled respect from the very enemy. In the days of adversity, he had learnt what the Boer Army lacked: discipline. And, with all his strength of will and all his strictness, he set himself to rule his burghers. He lashed the cowards mercilessly. He seldom carried a rifle, but he was never seen without his sjambok. He maintained an iron discipline and was inexorable if his curt orders were not swiftly carried out. He suffered no neglect of duty from common burghers or officers. His brother Piet, who had spent the time near Lindley doing nothing, while Chrisjan himself had acted with such great success at Roodewal Siding, was deprived of his rank, because he had allowed a convoy of 50 waggons, with a feeble escort, to enter Lindley unimpeded. In this way, Oom Chrisjan showed himself to be severe, but just, refusing to overlook any offence, even on the part of his own family. No offenders escaped him.

The general, with his iron frame, which knew no fatigue, often inspected his pickets at night in person. His burghers were more afraid of being surprised by their general than by the enemy. And, notwithstanding his harshness, all his men remained with him. Only a very few had run away to other commandoes or surrendered. The others were faithful to him to the death. They admired him for his uprightness, his fairness, his strict justice, his courage, his resolution, his calmness in the presence of danger. His mighty will swayed them all.

De Wet could lead his men into any fight. They had unlimited confidence in his generalship. They believed in him fanatically. They followed him as the Turks followed the green flag of Mohammed. He saved them repeatedly when escape seemed hopeless and when all the other officers were thinking of surrender. At such moments, I have no doubt that De Wet's mouth again assumed that resolute fold. He sat grimly for a while, huddled into himself, and then his plan was ripe. It was always a very simple, in no way complicated, plan: the egg of Columbus, in fact. And its very simplicity ensured its unfailing success.

As often as I read, in Europe, that De Wet had been hopelessly surrounded and had still succeeded in escaping, I used to think of his own words:

A Boer first gets dangerous when you succeed in surrounding him.

He uttered these words on the Modder River, at the time of the investment of Cronjé, after he had barely escaped being surrounded. This was the first time that he extricated himself from a British trap. How often he succeeded since! The Boers called him the "jackal," referring to the craftiness with which he made his way through any outlet. And yet it was determination rather than craftiness. De Wet would not surrender. He has said so himself:

"As long as it is possible — and it is always possible — for me to get through, escape and fight again, I shall do so. When necessary, I shall run away, and, if the others will not follow me, I shall run away alone. But surrender and lose our liberty: never!"

He prefered to take any dangerous work on himself personally, if he feared that another might fall back or waver at the crucial moment. He, with his nerves of steel, knew neither fear nor hesitation.

And he always escaped the threatening danger. History tells of the most wonderful deliveries. The traitor who brought a patrol to take De Wet prisoner when staying at a certain place found the bird flown when he returned. When the greater part of his followers were captured, De Wet escaped, as at Bothaville, on the 5th of November 1900. When his pursuers thought that they had him at last, he was far away. They thought to find him in a house: it so happened that he was sleeping outside. This happened many times. Innumerable attempts were made to catch him, and all failed, whereas his plans to escape invariably succeeded. His men saw in this a higher Hand Which spared him. He had become to them the apostle of their liberty, and he wielded an unequalled power over them, which he knew how to employ with rare talent in the service of his country. At one time, he was with this commando; at another, with that. Accompanied only by a few trusted followers, he rode through the land. To-day he was here; to-morrow there. He needed little rest. He took it when he could. And it was then, perhaps, that he was most dangerous to his enemies, who, at such times, seemed to perceive his presence at three or four places at once. In those rare days of inaction, he thought out new plans and suddenly broke from his rest and darted through the country, striking his blows with inconceivable swiftness and sureness. When necessary, in a few days he would gather a great force round him, which as suddenly dispersed. Slowness did not exist for him. He felt that the enervating influence which he exercised over the enemy lay in the rapidity of his operations and movements, and he had carried discipline to so high a pitch that his men executed all his commands immediately and swiftly. He had taught the slow-moving Boer, whose "steady on, man" lay always on his lips, to be quick and resolute in all things.

De Wet, the man who is square of build and square in character, cannot endure half-patriots. He preferred to let them go from his commandoes, rather than remain. He himself sacrificed all for liberty. He expected his followers to be prepared to do as much. The honest enemy he respected. He treated his prisoners as well as, in the circumstances, he could. But on traitors to his nation he swore vengeance. He would have liked to make short work of all the Boers who acted as guides to the enemy of their country, of all his countrymen who had taken up British arms to fight against him and his faithful followers. He could forgive, though he could not understand, a man who took the oath of neutrality because he was weary of the struggle for independence ; but that a man should assist the enemy made him furious. For De Wet is passionate and hot-tempered. He would fly out against his highest officer as against the lowest burgher. But, when it was a question of saving his fellows at the risk of his own life, he knew no moment's hesitation and would at once obey the impulse of his heart. The loss of a burgher who had done his duty touched him deeply, though he said little, the sombre, silent man.

When Lieutenant Nix, the Dutch military attaché, was fatally wounded at Sanna's Post and had to be left behind in a farm-house, because De Wet had no ambulance with him, he stood long by the bed-side of the wounded man, holding his hand in his own. The tears stood in his eyes as he expressed his regret at having to leave the gallant young Hollander, and he could not tear himself away until his commandoes were far ahead with the booty.

Under a hard and sombre husk, De Wet conceals a noble kernel, a sensitive heart, an honourable character and a sacred love of country. It was shortly after he had heard of the destruction of his homestead. He rode off accompanied by only two faithful comrades, Generals Froneman and Piet Fourie. It was a flying, silent ride. When they approached his place, De Wet rode on alone, while the two officers posted themselves on a neighbouring kopje. The great general remained long away. He knelt by the grave of one of his children and prayed : and then, with one last look, printed the image of the destruction deep in his memory. Then he returned to his two silent companions, and the ride back was resumed with the same silence as before. This time there gleamed no moisture in De Wet's eyes; but his face was set and pale and the lips pinched together.

For long, no one knew of this pilgrimage to De Wet's destroyed dwelling, until General Fourie told the story his sacred conviction that he saw a higher Power in all things, and he was prepared to accept his lot, whatever it might be, at the hands of the Supreme Being. But this he had said to England, that his death or his capture should not put an end to the struggle in the Free State. [131-38]

Bibliography

Rompel, Frederik. Heroes of the Boer War. London: “Review of Reviews” Office; The Hague and Pretoria: the “Nederland” Publishing Co., 1903. Internet Archive version of a copy in the University of California Library. Web. 22 December 2014.

Victorian

Web

Political

History

The Boer

War

Next

Last modified 22 December 2014