This article has been peer-reviewed under the direction of Kristen Guest (University of Northern British Columbia) and Ronja Frank (Memorial University, St John's, Newfoundland). It forms part of the Equine Breed and the Making of Modern Identity project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

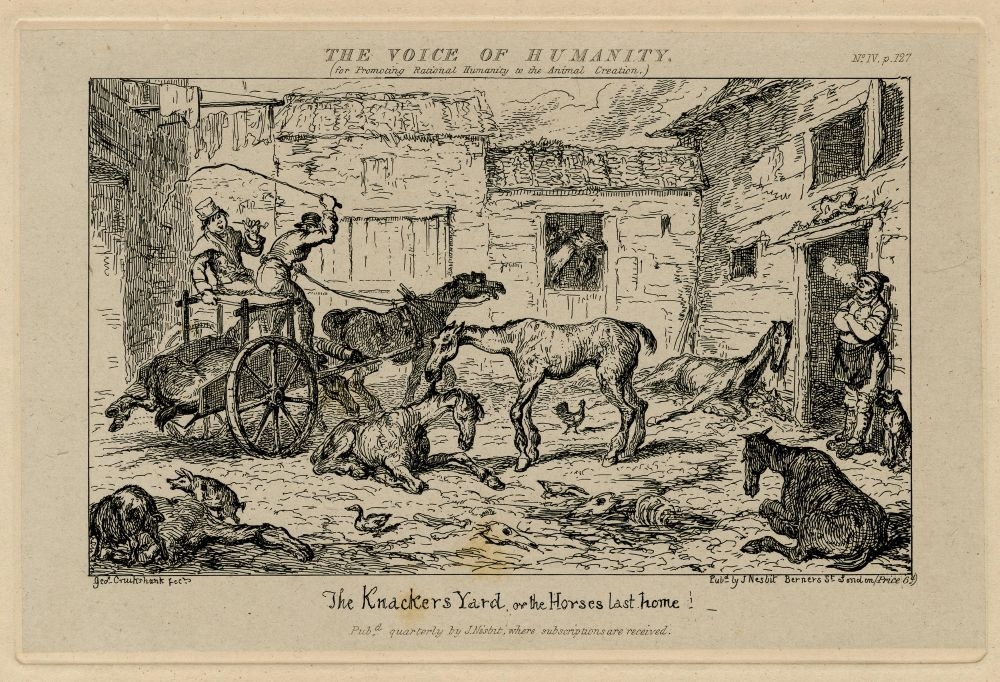

orses were widely used for transport and agriculture in the nineteenth century, and often worked until they dropped. The knacker, or knacker man, collected and processed dead and incapacitated animals — most often horses — into useable by-products such as meat, fats, tallow, bone meal, gelatin, glue, and leather. His work was part of everyday life in the nineteenth century, and his trade was plentiful and often lucrative. In London Labour and the London Poor, Henry Mayhew notes that there were nearly twenty knackers' yards in London at midcentury: "the proprietors of these yards purchased live and dead horses they contract for these with most large firms such as brewers, coal merchants, and large cab and bus yards, giving so much per head for their old life and dead horses throughout the year. The price they pay is from £2 to 50s. the carcass"(182). Both live horses and carcasses were also obtained from the country, Mayhew explains: "The dead horses are brought to the yard, two or three upon one cart, and sometimes five. The live ones are tied to the tail of these carts, and behind the tail of each other. Occasionally, a string of 14 or 15 are brought up, head to tail, at one time. The live horses are purchased merely for slaughtering" (182).

George Cruikshank's portrayal of the knacker’s yard in The Knacker's Yard, or the Horses last home! (1831). © The Trustees of the British Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

The mare Ginger's fate in Anna Sewell's Black Beauty was that of many working horses in Victorian England. As Skinner (the owner of a cab company in the novel) suggests of his cab horses, "my business, my plan is to work 'em as long as they will go, and then sell 'em for what they'll fetch, at the knackers or elsewhere" (186). During the mid- to late- nineteenth century, the average working life of an Omnibus horse was between two and five years. During this time, overworked and overloaded horses were so common the situation required policing. As a London newspaper reported in 1854:

Several flagrant cases of cruelty to horses, by driving with heavy loads, when quite unfit for any kind of work, have been brought before the police magistrates lately. One of the worst cases was that of Mr Robert Cheal. He is a carrier to Her Majesty, and it was while drawing a wagon heavily loaded with wine for the royal cellar, that one of his horses was perceived in the most deplorable condition. An officer deposed to see in the car a man, Thomas Perren, standing at the horse's head, and lashing the poor beast most unmercifully. The wagon was on a dead level, but the horse was quite unable to stir. Mr Beadon, the magistrate before whom the charge was made, satisfied himself as to the state of the horse, and said it was only fit for the knacker. The wagon was stated to have contained 54 dozen of wine, a heavy load even for a horse in good condition." (67)

Though they usually dealt with old, sick, or decrepit animals, knacker men knew equine anatomy inside out, and occasionally a horse was saved by shrewd foremen who understood their remaining value. As Mayhew explains:

If among the lot purchase there should be chance to be one that is young, but in bad condition, this is placed in a stable, and fed up, and then put into their carts, or sold by them, or let on hire. Occasionally a fine horse has been rescued from death in this manner. One person is known to have bought an animal for 15 shillings for which he afterwards got £150. Frequently young horses that will not work in cabs, such as jibs, are sold to the horse slaughters as useless. These are kept in the yard, and after being well fed, often turn out good horses, and are let for hire. (182)

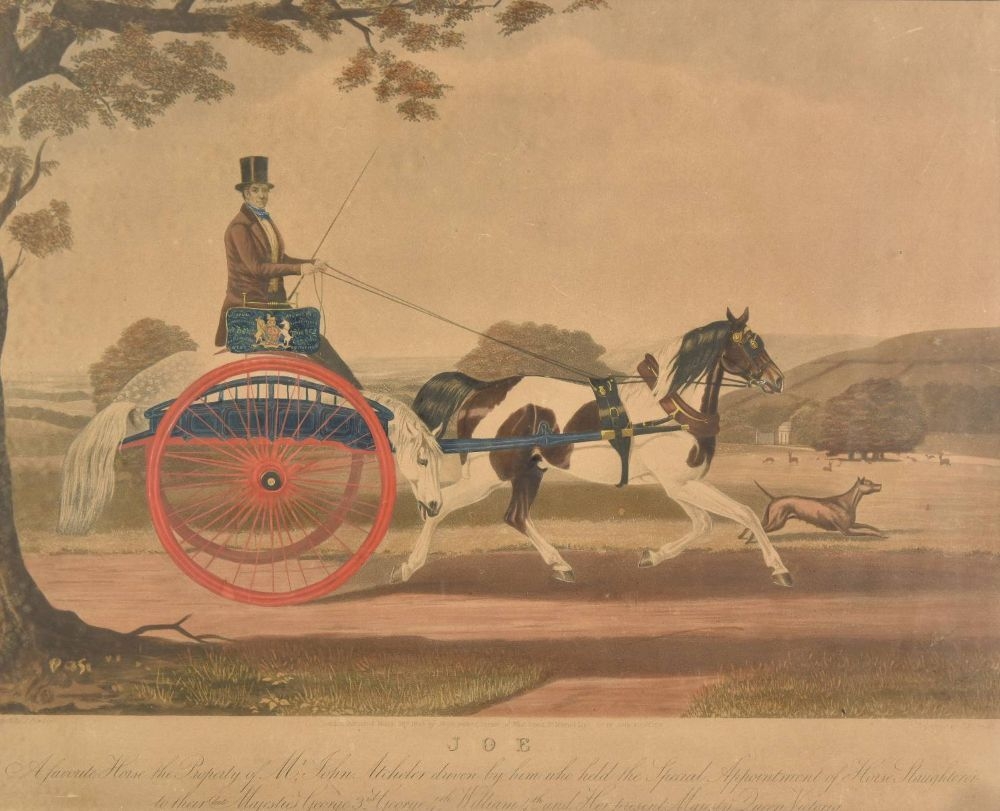

Across London, dozens of knacker men operated flat carts that could carry up to five carcasses at a time. By the mid-nineteenth century, the panelled sides and boards of knackers' carts displayed their proprietors' names and some had painted decoration that served as advertisement for the service. The average yard processed sixty horses each week, and large London yards might deal with as many as one hundred and fifty. With the meat selling at an average rate of 21/6d per pound and with the addition of hiring and selling rescued horses, the slaughter man could realize a decent income. Some even retired, having earnt enough to secure the purchase of farmland. C. N. Smith's painting of Joe Atcheler driving a Dead Horse Cart depicts a prosperous knacker man, proud of his patronage, with a well maintained horse and cart. Atcheler held a special appointment as horse slaughterer from the time of George III through Queen Victoria's reign, and engravings of Smith's painting circulated widely during the late nineteenth century.

Smith (C. N.). Joe (1849). A favourite horse the property of Mr. John Atcheler, driven by him who held the special appointment of Horse Slaughterer to their late Majesties George 3rd., George 4th., William 4th and Her present Majesty Queen Victoria. Courtesy of Dominic Winter Auctioneers.

Knackers' carts were constructed specifically for the job, with a design that used gravity to load the carcass onto the flatbed. On arrival at the scene, the knacker man would unharness the cart horse, remove the single plank seat and tailboard from the cart, and back the vehicle up to the carcass. With the shafts tilted up into the air, the cart rested on a solid wooden ramp which projected at an angle from the back of the vehicle. In some cases, the wooden rollers, like those on the floors of a hearse, were set into the ramp and floor to ease passage of the carcass. Under the front of the cart, a detachable thick wooden roller with a chain was carried along with an iron bar, like a crowbar, which fitted into the holes of the roller to form a lever that turned the winch mechanism. This detachable roller was fitted into two brackets that were bolted on top of the shafts, just behind the breeching dees. A cogwheel on the end of the roller enabled the ratchet device to be used on the near side. The chain was drawn back through the body of the cart and fastened around the hind legs of the dead horse. By inserting the iron bar into the roller and turning it against the ratchet, the knacker man could slowly ease the carcass up the ramp and into the cart. When the weight of the carcass was over the axle, the shafts could be lowered easily. Once the carcass was secured, the roller returned to its position under the vehicle and the horse was harnessed to the cart again.

Knacker men at work in William Strang's Knackers (1894). National Galleries of Scotland.

At the yard, knacker men worked for a wage of around 4s per day processing carcasses. Because these could only be boiled during night due to the stench they created, knackers worked around the clock. Horses were presented with their manes hogged and their tails clipped to the dock, as horsehair was sold for use in the upholstery trade and to coachbuilders for use in cushions and seating on carriages. Carcasses were sectioned with almost every part sold on to other trades. Meat from the hind quarters, fore quarters, the throat, neck, brisket, back, and ribs as well as the kidney, heart, tongue, and liver were sold to carriers who would sell it from barrows. Prior to the carriers purchasing the meat, it was prepared by being submerged in large coppers, nine feet in diameter. Mayhew writes that "each of these pans will hold about three good sized horses. Sometimes two large Brewers horses will fill them, and sometimes as many as four poor cab horses may be put into them. The flesh is boiled about an hour and twenty minutes for a killed horse, and from two hours to two hours and twenty minutes for a dead horse. The flesh when boiled is taken from the coppers, laid on the stones, and sprinkled with water to cool it. It is then weighed out in pieces" (182).

As part of the rendering process, bones were boiled down for hours to draw out the fat which was used to grease harnesses, the axles of carts and carriages, cricket bats, and leather sport shoes. The remaining bones were then sent to cutlery manufacturers to be used for handles, to coach builders for use in carriage interiors, or ground and sold as fertiliser for gardens and farmland, while hooves were used to make glue.

Nineteenth-century veterinarians, whether fully qualified or in training, frequently spent time at the knacker's yard carrying out research into causes of death or signs and symptoms of various illnesses in horses. In 1879, Hugh Owen Thomas noted in The Past and Present Treatment of Intestinal Obstructions (a treatise on colic) that one knacker man informed him that "he cut up about two thousand [horses] annually, and that a large percentage of horses die from this malady, and that their life seldom prolonged the seventh day" (124). Other veterinary professionals spent hours observing greasy heels on carcasses to investigate a potential connection to tuberculosis (Bartholomew 99). Because the knacker man's yard also served as a place to carry out post-mortems, a close eye was kept on the running and cleanliness of the place by the Royal Institute of Veterinary Surgeons (founded in 1844).

While the knackerman and dead horse carts were part of everyday city and rural life during the nineteenth century, the decline of horses as labourers in agriculture, industry and transportation in the early twentieth century saw a dramatic decrease in the number of knacker yards. In their place, hunt kennels became the primary service for dispatching and removing carcasses, though the knacker trade still exists, now undertaken by Fallen Stock Collectors who assist farmers with the correct management of carcasses.

Bibliography

Bartholomew, Charles. The Turkish Bath in Health, Convalescence, Etc. London: Ward, Locke, and Tyler, 1869.

Cruikshank, George. The Knacker's Yard, or the Horses last home!. 1831. The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/1442331001. Web. 20 April 2025.

"Law and Crime." Household Narrative of Current Events. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1854.

Mayhew, Henry. London Labour and the London Poor. Volume I. London: Griffin, Bohn and Co., 1861.

Sewell, Anna. Black Beauty. (1877) Edited by Kristen Guest. Broadview, 2016.

Strang, William. Knackers. 1895. National Galleries of Scotland, David Strang Gift 1955, https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/32187. Web. 20 April 2025.

Thomas, Hugh Owen. The Past and Present Treatment of Intestinal Obstruction. 2nd edition. H.K. Lewis, 1879.

Created 13 June 2025