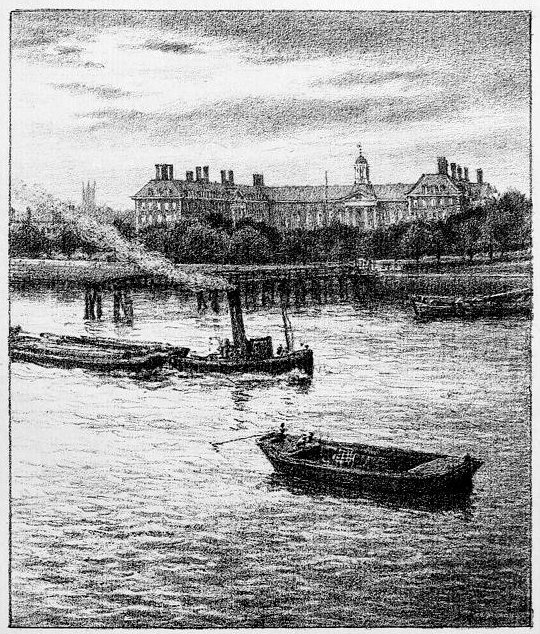

Chelsea Hospital

T. R. Way

Signed and dated 1899

Lithograph

Source: Reliques of Old London, 53

Other Scenes of Chelsea Hospital

Text and formatting by George P. Landow

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Victorian artists —> The Thames —> T. R. Way —> Next]

Chelsea Hospital

T. R. Way

Signed and dated 1899

Lithograph

Source: Reliques of Old London, 53

Other Scenes of Chelsea Hospital

Text and formatting by George P. Landow

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the Boston Public Library and the Internet Archive and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite it in a print one.]

The two great institutions — for the support of old and disabled soldiers and sailors — are both ornaments to the riverside, and both had Wren for their architeft; but it would be difficult to find two buildings more unlike. Chelsea Hospital is a charming old-fashioned mansion of red brick with stone dressings, having a centre and two wings. It has been said that this building shows more effect with less means than any other of Wren's secular buildings, but there are little or no marks of originality about it. On the other hand Greenwich Hospital is singularly original in conception, and we may therefore guess that Vanbrugh. who was an origmal genius, had a considerable hand in the plan of Greenwich.

The first building on the site was “King James's College” at Chelsea, founded in 1610 by Dr. Matthew Sutcliffe, Dean of Exeter, “to the intent that learned men might there have maintenance to aunswere all the adversaries of religion.“ This attempt to form a sort of headquarters of religious controversies was not very successful, and after Sutcliffe's death the place gradually decayed. Archbishop Laud called it “Controversy College.”

After the Restoration the College was given to the Royal Society by the king, but it was not made use of, and in 1682 the king bought it back for £1,300, and the building of the hospital was proceeded with. Charles II. was the fotmder, but to Sir Stephen Fox and John Evelyn the idea of the foundation was largely due. Fox strongly urged the need of such an institution on the king.

There is a tradition that Nell Gwyn suggested the foundation of the hospital, but neither contemporaiy evidence, nor official records give any corroboration to this tradition, although there is still a long-established public-house with the sign of “NellGwynne” in the Pimlico Road.

The Royal Hospital accommodates 540 in-pensioners, and the out-pensioners are said to number nearly 70,000. Parliament makes an annual grant of about £24,000 for the support of the hospital. The buildings contain much of interest, and are intimately associated with many distinguished men. The body, of the great Duke of Wellington lay in state in the Chapel previous to its interment in St Paul's.

The grounds leading down to the river are well kept and pleasant to look upon. They were the scene of two of the most interesting exhibitions ever arranged in London, viz., the Military Exhibition in 1890, and the Naval Exhibition in 1891.

The hospital is still known in the neighbourhood as “The College.”

Way, T. R., and H. B. Wheatley. Reliques of Old London upon the Banks of the Thames and in the Subburbs South of the River. London: George Bell and Sons, 1909. [title page] Internet Archive version of a copy in the Boston Public Library. Web. 22 April 2012..

Last modified 22 April 2012