[The following passages come from the author's As Good as God, as Clever as the Devil: The Impossible Life of Mary Benson, which is reviewed on this site. — Joe Pilling

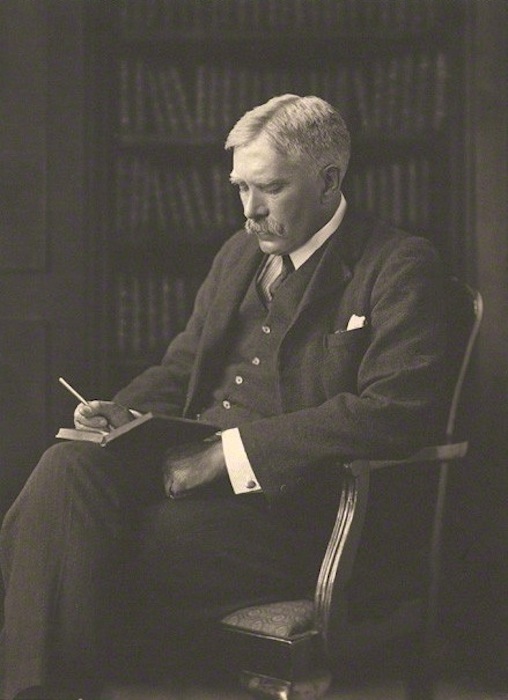

Mary with two of the "supporting cast" here. Left to right: (a) Mary Benson in her early seventies. Source: E. F. Benson, frontispiece. (b) Dame Ethel Mary Smyth, by Bassano Ltd, 1927. © copyright National Portrait Gallery, by kind permission. (c) A. C. Benson (Arthur here), by Vandyk, c.1911. © copyright National Portrait Gallery, by kind permission.

The writer Arthur (A. C.) Benson's view of his mother

It was the human being beneath that she was in search of," wrote Arthur, "and that was all she cared about." From the pinkest, most tongue-tied curate to the starchiest of aristocrats, Mary could set people at ease, soften social edges, coax out conversation. She was herself a sparkling conversationalist., "really brilliant," marvelled Arthur. Alas, Mary's flow of talk was "so fanciful, humorous, suggestive, incisive, and her power of transition was so great" that Arthur — like everyone else who knew her and admired her wit and deadly repartee, and to the great loss of posterity — could only throw up his hands and admit that it was utterly impossible to reproduce the quality of her conversation in print. [Bolt 162]

Ethel Smyth on why she loved “Ben” (Mary)

[Smyth, composer, writer and suffragist, on why she loved Ben (the "so intensely appropriate monosyllable" adopted for Mary Benson by some of her closest friends)]

"The reasons for which I love you are unshakeable," Ethel wrote to Ben, "here are some of them; your fire, your intensity, your power of sustained effort, your extraordinary grip over other souls, your intellect, and, above all, in the words of a prayer I like, 'your unconquerable heart.'" Ethel appreciated another side of the Archbishop's wife. She enjoyed "the particular look of devilment one knew so well on her face," her delight in a little social wickedness, her acute sensibility to absurdities. On a more fundamental level, Ethel discerned the dexterity of spirit Mary needed to sustain herself as a dutiful wife, effervescent hostess and sympathetic friend. When Ethel said that Mary Benson was "as good as God, and as clever as the Devil," the remark struck such a resonance among those who knew her well, that it did the rounds of their friends. [Bolt 176-77]

Mary's "Thanksgiving prayer"

Mary once wryly sent Ethel a "Thanksgiving to be used irregularly" that read: "I thank thee, O Art, that I am not as other women are — strait-laced, narrow-minded, dogmatic — or even as those Bensons." [Bolt 178]

Mary and "carnal affection"

Lucy Tait's arrival in Lambeth Palace had led Mary once again on to the tricky terrain where she had so frequently tripped up in the past. "I feel nearer her now than I have done these 6 years," Mary wrote in her diary of the summer of 1896. "O God draw us together more and more — if I might — if I might! but this is as it shall please thee." Once again Mary struggled with "carnal affection" and its place in a loving friendship so intense that the union seemed to her a gift of God. She writes of her shame, of how "last night I fell again," and sometimes more esoterically: "I must put away forever the red failing." Mary owned a leather-bound copy of Thomas à Kempis's The Imitation of Christ, which Edward had given her for her fiftieth birthday in 1891, soon after Lucy's arrival. Underlined in pencil are passages that portray religious life as a constant struggle against a powerful enemy, lines which uphold temptation as an offering from God that encourages us to fight sin and emerge triumphant, together with texts such as:

And, save you act with violence,

You will not crush your sin.

Mary Benson records a private prayer in her diary, in August 1896

O merciful God, grant that the Old Adam in me may be so buried that a new man may be raised up in me.

Grant that all carnal affections may die in me and that all things belonging to the Spirit may live and grow in me.

Grant that I may have power and strength to have victory and to triumph against the devil, the world and the Flesh. [Bolt 211-12]

Mary, who had "every sympathy for scepticism," dealing tactfully with her son Arthur

Are you coming to church, Arthur?" she asked one Sunday, noticing he wasn't quite dressed for the purpose.

"Would you like me to go?"

I should like you to like to go, but I don't want you to go because you think I should like you to go." [Bolt 258]

Related Material

- Review of Rodney Bolt's As Good as God, as Clever as the Devil: The Impossible Life of Mary Benson

- An Unequal Marriage (on the Bensons' marriage)

Illustrated and formatted by Jacqueline Banerjee. You may use the image from E. F. Benson's biography without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Sources

Benson, Edward Frederic. Mother. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1925.

Bolt, Rodney. As Good as God, as Clever as the Devil: The Impossible Life of Mary Benson. London: Atlantic Books, 2011.

Last modified 3 June 2014