scar Wilde’s poem “The Sphinx” depicts a sexually voracious monster — the legendary Sphinx, who, in Wilde’s work, has been the lover of many classical figures, among them Ammon, the god Amenalk, the gryphon, and the Tragelaphos (a goat-stag monster of myth). Throughout the poem Wilde makes references to figures of legend.

scar Wilde’s poem “The Sphinx” depicts a sexually voracious monster — the legendary Sphinx, who, in Wilde’s work, has been the lover of many classical figures, among them Ammon, the god Amenalk, the gryphon, and the Tragelaphos (a goat-stag monster of myth). Throughout the poem Wilde makes references to figures of legend.

The focus upon the sphinx and the accompanying parade of largely obscure Egyptian mythical figures may seem elitist and showy — after all, Greek and Roman myths are much more widely known, and there are a number of western European mythical creatures who could play the part of seductress in Wilde’s poem as well as any sphinx. Punch magazine seemed to be of this mind. The July 21, 1984 issue published a parody entitled, “The Minx — A Poem in Prose.” The entire effort is a farce of Wilde’s inquisition regarding the Sphinx’s numerous past love affairs. The speaker instead queries, “Dear me! Is it true you played golf among the pyramids?” to which the Sphinx replies, “Perfectly untrue. You see what absurd reports get about!” (p. 33)

Two plates illustrating Eygptian design from Owen Jones's immensely influential The Grammar of Ornament (1865). [Click on thumbnails for larger images. Images added by George P. Landow]

However, judging by the fads of the day, a poem focusing on the wonders of Ancient Egypt was perfectly acceptable and not snobbish in the least. Since Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt in 1798, Europe had been fascinated by the pyramids, the Sphinx, and by some of the first and most impressive archaeological sites in the world. The Times of London published numerous excited letters from archaeologists such as Sir Andrew MacCallum, whose letter documenting his discovery of a secret rock chamber tomb in the Temple of Aboo Simbel was printed with great excitement on the eighteenth of March, 1874. Archaeology in Egypt made many headlines in The Times, and it also provoked a number of letters to the editor. One of these, from J. Britton entitled “Egyptian Antiquities,” which appeared on January 14, 1834, argued that Egyptian Art is true culture of an extraordinary caliber, and that bland England should acquire as much of it as possible to accrue good cultural standing.

“Every one, high and low, has heard of Egypt and its primeval wonders,” declares Georg Ebers with confidence in his two-volume Egypt: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque, published in 1878. “The child knows the names of the good and the wicked pharaohs before it has learned those of the princes of its own country.” (p. iiv) Ebers is at a loss to explain this phenomenon, however; he can merely query the reader: “Why is it that its [Egypt’s] name, its history, its natural peculiarities and its monuments, affect and interest us in quite a different manner from those of the other nations of antiquity?”

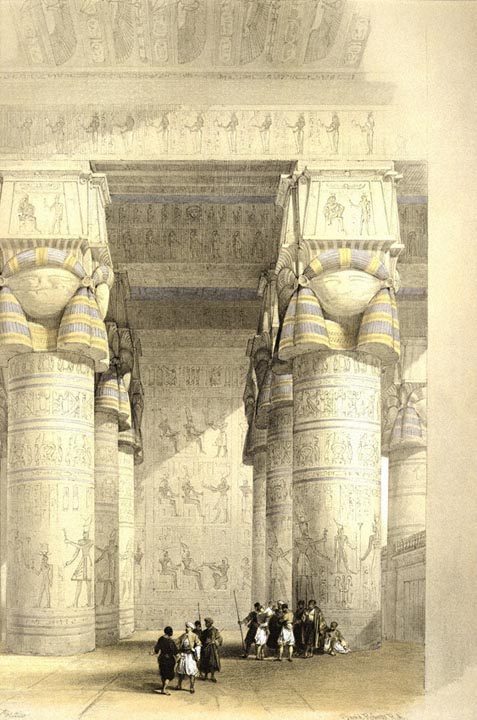

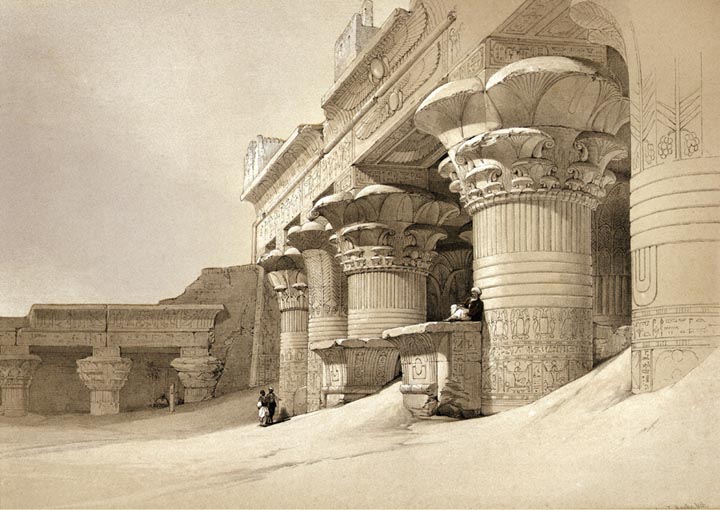

Paintings and lithographs by David Roberts, RA of Eygptian scenes: (left to right) Dromos, or outer Court of the Great Temple at Edfou in Upper Egypt (1840); Karnac (1842); View from under the Portico of the Temple of Dendera (1842). Façade of the Pronaos and the Temple of Edfou (1842). [Click on thumbnails for larger images.]

In fact, the Victorians were singularly obsessed with Egypt, perhaps in part because there existed a pervasive belief that Egypt was the Britain of the ancient world — a superior, highly advanced civilization conquering all of the land within its reach. Egypt was a founding civilization; all other Eastern civilizations were, as a printed guide to the 1985 Exhibition of the Art of Ancient Egypt at Britain’s Burlington Fine Arts Club states, “pale imitations” (p. xii) of vivid Egyptian culture. “Reference has been made to Greek influence on Egyptian art,” reads the Burlington Club program, but it assures the reader that “in the case of influence generally, Egypt has been the donor, not the recipient.” (p. xiii) The program later observes that, “The influence of Egyptian art on that of the other great civilizations of antiquity can be traced in all directions.” (p. xiii)

The fascination with Egypt did not stop at intellectual curiosity. Artifacts — termed “antiquities” at the time — from Egyptian ruins and ancient tombs were in high demand as décor for well-to-do British homes. The British felt that the transporting of Egyptian antiquities to their homes was a perfectly acceptable method of preservation, because, as Ebers points out in his volume (under a section entitled, “The Resurrection of the Antiquities of Egypt”), by the dawn of the Renaissance “The antiquities of Egypt, which for many centuries had been utterly neglected, had already begun to attract the attention of the learned men of Europe.” (p. 37)

In the process of taking souvenirs, the traditional imperialist argument comes into play — clearly the Egyptians’ artifacts, temples, and figurines ought to be given over to the control of the British, who can protect them responsibly.

Some of the plans to transport Egyptian artifacts were drastic. �AN ANGLO-EGYPTIAN’ wrote a letter to the editor of The Times on May twentieth, 1872 protesting Sir James Alexander’s cockamamie scheme to move Cleopatra’s Needle to the banks of the Thames. In it, he argues that not only would the Needle be difficult to move, but it is architecturally unsound and not worth attempting to preserve over a perilous journey from Egypt to London. In 1877, despite these arguments, the obelisk was successfully moved to London and erected there.

Ancient Egyptian trinkets were also quite popular. Some members of the nobility, who could afford such things, were avid collectors of jewelry, figurines, ornamental boxes, and scarabs. The Burlington Fine Arts Club 1985 exhibition program lists thirty-eight contributors in the front and credits each with the part of the collection provided. Only three of the contributors are museums. An additional one is University College. The other thirty-three, however, are all private collectors, most of them members of the club, some of whom have amassed collections large enough to receive their own display cases.

The mania for Egypt was not limited to collecting; Verdi’s opera A�da (set in Egypt) was quite popular, as were books documenting travels to Egypt. Lavish illustrations of scenes from Egypt can be found in The Illustrated London News on December sixteenth, 1893. (p. 772).

Egyptomania only grew as archaeological exploration of Egyptian sites began in earnest, and it exploded into a worldwide phenomenon following the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, but its roots were very much Victorian and were reflected in the works of the time. Wilde, who embraced the idea of art for art’s sake, was certainly not the first to embrace the trend.

Related Material

- The True Riddle of the False Sphinx

- The Riddle of "The Sphinx": Difficult Questions and Troublesome Answers

- The Silent Predator

- Constructing the Decadent Sphinx

- Subjects in Nineteenth-Century Painting and Literature — The Sphinx

Resources

AN ANGLO-EGYPTIAN. “Cleopatra’s Needle.” Letter to Ed. The Times Online Archive. Web. (18 May 1872).

Britton, J. “Egyptian Antiquities.” Letter to Ed. The Times Online Archive. Web. (14 Jan 1831).

Burlington Fine Arts Club. Exhibition of the Art of Ancient Egypt. Printed for Burlington Fine Arts >Club: London, 1895.

Ebers, Georg. Egypt: Descriptive, Historical, and Picturesque. Trans. Clara Bell. Vol. 1 & 2. Cassell: London, 1878.

“The Minx — A Poem in Prose.” Punch. (21 July 1894): 33. Print.

Wilde, Oscar. “The Sphinx.” The Victorian Web. Ed. George P. Landow. Web. 13 May 2010.

Last modified 11 September 2003