s a person who has spent his whole working life in the field of art and art education, it is perhaps unsurprising that I was first strongly taken by Ruskin through sight of his drawings; not his writing. Although my mother gave me a copy of Modern Painters vol 1 when I was a young art student I did not read it at the time, nor was there much mention of Ruskin, or the Pre-Raphaelites at the art college that I attended. My interests lay in modern artists such as Mark Rothko. I clearly remember seeing Ruskin’s drawings for the first time some ten years later when a visiting lecturer brought some framed originals into the college art department at Lancaster in which I taught in the early 1970s. From that point my interest in Ruskin began to grow. I joined Jim Dearden’s The Ruskin Association and The Guild of St George and at the Ruskin Museum at Coniston got to know very well John and Margaret Dawson, the excellent curators. My wife and I became members of the first committee of the newly formed The Friends of Ruskin’s Brantwood.

Some of my academic work began to focus on Ruskin as a draughtsman along with his writings on art education. This led to an early essay aimed at art teachers, ‘Looking, Drawing and Learning with John Ruskin at the Working Mens’ College’ published in the Journal of Art and Design Education (1988). George Landow’s book, The Aesthetic and Critical Theories of John Ruskin (complete text, 1971) and Robert Hewison’s John Ruskin: The Argument of the Eye (complete text, 1976) were both inspirational and particularly important. M/p>

The arrival at Lancaster of the Whitehouse Collection and Michael Wheeler’s work in establishing the new Ruskin Library and Ruskin Programme, made for exciting times at Lancaster University. This continued over many years under the subsequent directors, Robert Hewison, Keith Hanley and Stephen Wildman. International conferences at the university allowed one to meet Ruskin scholars from many parts of the world. During this period I was Head of the Department of Art, Design and Technology at S. Martin’s College, Lancaster, very much concerned with contemporary art and design degrees and later became professor of art education and visiting professor in the Ruskin Research Centre at Lancaster University.

Left: The Lamp of Memory edited by Michael Wheeler. Right: Ruskin’s Artists edited by Robrt Hewison. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In earlier essays I explored the development of Ruskin’s architectural drawings in ‘Ruskin and the Tradition of Architectural Illustration’ in: The Lamp of Memory: Ruskin, Tradition and Architecture (1992), edited by Michael Wheeler and N. Whiteley. I also wrote about his work in art education in the United Kingdom and United States, in ‘According to the requirements of his scholar’s: Ruskin, drawing and art education’ in Robert Hewison’s book Ruskin’s Artists: Studies in the Victorian Visual Economy (2000). This book of essays from the Ruskin Programme at Lancaster was written to coincide with the exhibition at the Tate Gallery, Ruskin, Turner and the Pre-Raphaelites (2000), curated by Robert Hewison, Ian Warrell and Stephen Wildman.

Around 2000, funding was achieved from The Leverhulme Trust for a hypertext project on Modern Painters Vol 1 and with insights following George Landow’s visit to Lancaster some members of the Ruskin Programme produced An electronic edition of Modern Painters Vol 1 (2003), edited by Lawrence Woof, for which I wrote the notes on British and German Painting and reviewed all the contributions as Consultant Annotations Editor.

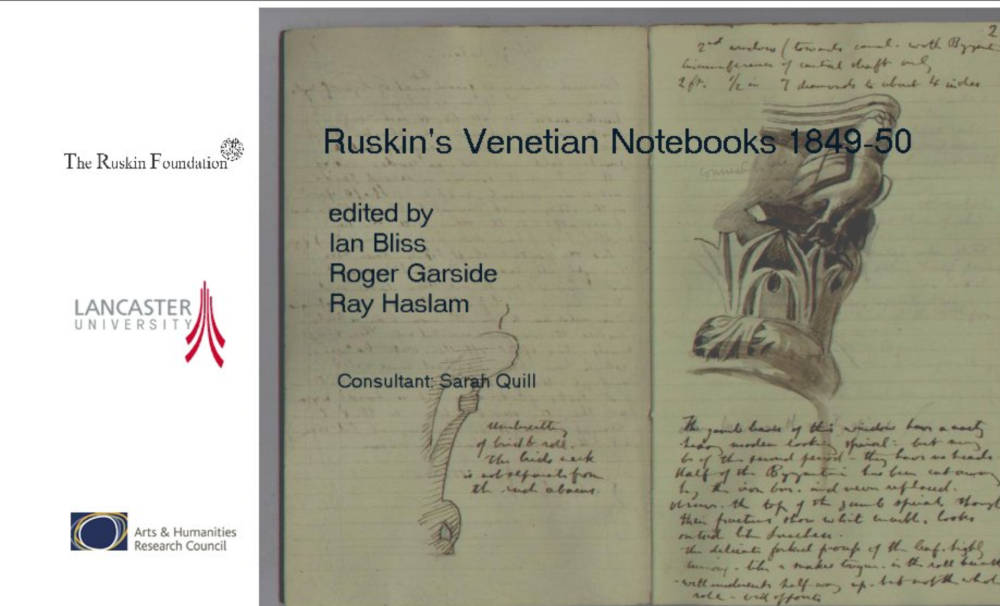

This was followed by a larger hypertext project funded by the AHRB over a number of years and resulted in the publication of Ruskin’s Venetian Notebooks which I edited with Ian Bliss and Roger Garside. This project gave me the opportunity to continue the close study of Ruskin’s architectural drawings through the transcription and editing of the eleven small notebooks full of brilliant details of architectural features along with over 200 sheets of architectural drawings with his meticulous annotations. Having hand copied every single page of notes and drawings made by Ruskin in the smaller notebooks and worksheets I felt more able to understand just what he saw and was trying to show us in The Stones of Venice. My handmade copies of the notebooks also proved most valuable as I was able to carry them with me during my research visits to Venice. Now, of course, researchers and visitors to Venice can take their electronic tablets with them and see every page of Ruskin’s Venetian Notebooks and Worksheets on site. It can be accessed through the Lancaster University website, The Ruskin: Museum of the Near Future.

Last modified 4 May 2019