Eliza Sydney

Although Reynolds’s devotes most of The Mysteries of London to combinations of sensational plots in which innocent victims are fleeced and even destroyed by swindlers, which allows him to attack everything from class bias in the police and courts to details descriptions of dreadful poverty, he also throws bits of romance and straightforward sexual relationships into the mix. And for this he requires beautiful women, and his descriptions of female beauty give us an idea what his readers found beautiful. Here, for example, is how Reynolds introduces Eliza Sydney:

A female of great beauty, and apparently about five-and-twenty years of age, was reading in that bed. Her head reposed upon her hand, and her elbow upon the pillow: and that hand was buried in a mass of luxuriant light chestnut hair, which flowed down upon her back, her shoulders, and her bosom; but not so as altogether to conceal the polished ivory whiteness of the plump fair flesh.

The admirable slope of the shoulders, the swan-like neck, and the exquisite symmetry of the bust, were descried even amidst those masses of luxuriant and shining hair.

A high and ample forehead, hazel eyes, a nose perfectly straight, small but pouting lips, brilliant teeth, and a well rounded chin, were additional charms to augment the attractions of that delightful picture.

This “female of great beauty” — odd that Reynolds doesn’t call her a woman or a girl — turns out to be the person whom we first met as Walter Sydney. Having unveiled that “he” is in fact a cross-dressing young woman pretending to be a man in order to obtain her dead brother’s inheritance, the narrator describes a voluptuous sexual setting in which for the young woman who appears an odalesque kissed by sunbeams.

The whole scene was one of soft voluptuousness — the birds, the flowers, the vase of gold and silver fish, the tasteful arrangements of the boudoir, the French bed, and the beautiful creature who reclined in that couch, her head supported upon the well-turned and polished arm, the dazzling whiteness of which no envious sleeve concealed!

From time to time the eyes of that sweet creature were raised from the book, and thrown around the room in a manner that denoted, if not mental anxiety, at least a state of mind not completely at ease. Now and then, too, a cloud passed over that brow which seemed the very throne of innocence and candour; and a sigh agitated the breast which the sunbeams covered as it were with kisses. [Ch. 4, “The Boudoir”]

In chapter 23 Reynolds’ narrator, who reminds us that Eliza no longer is dressing like a man, again details aspects of her beauty:

Dressed in the garments which suited her sex, Eliza was a fine and elegant woman — above the common female height, yet graceful in her deportment, and charming in all her movements. Her shoulders possessed that beautiful slope, and the contours of her bust were modelled in that ample and voluptuous mould, which form such essential elements of superb and majestic loveliness.

Although so long accustomed to masculine attire, there was nothing awkward — nothing constrained in her gait; her step was free and light, and her pace short, as if that exquisitely turned ankle, and long narrow foot had never known aught save the softest silken hose, and the most delicate prunella shoes.

In a word, the beauty of Eliza Sydney was of a lofty and imposing order; — a pale high brow, melting hazel eyes, a delicately-chiselled mouth and nose, and a form whose matured expansion and height were rendered more commanding by its exquisite symmetry of proportions.

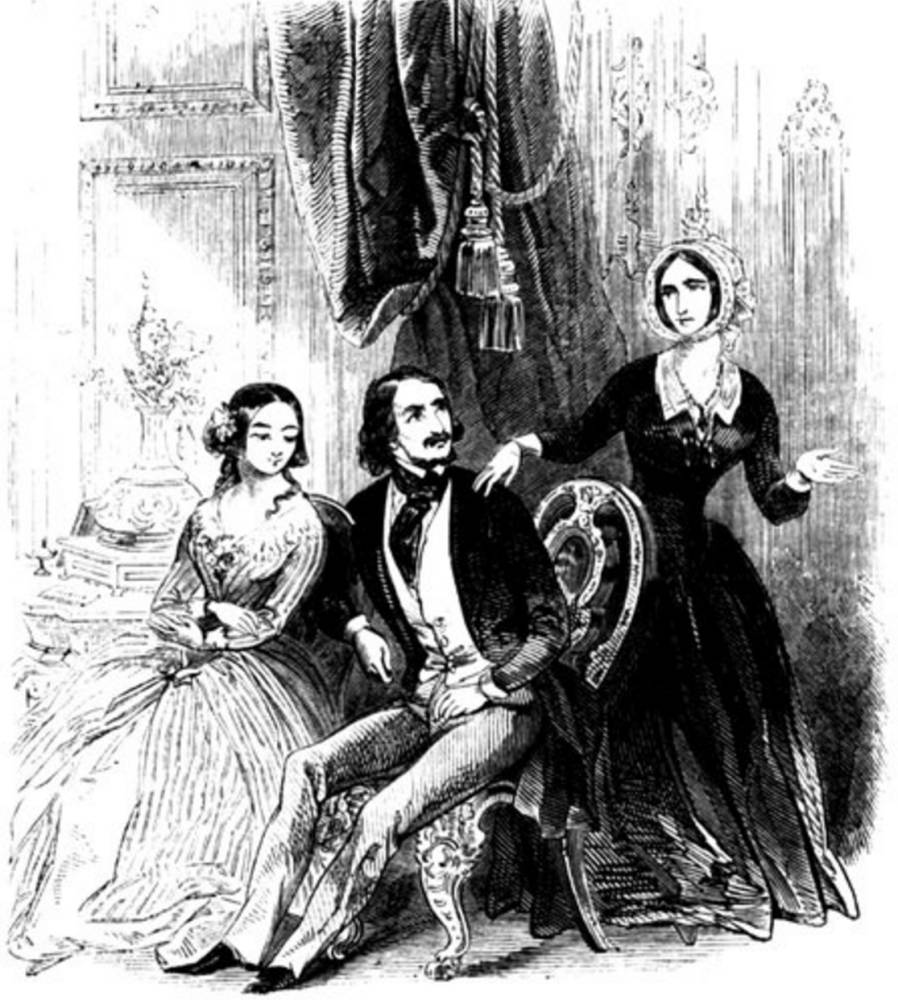

Reynold’s illustrator, G. Stiff, depicts some of the novel’s beautiful women: Left: The Marquis of Holmesford’s Harem. Middle: Katherine Markham and Eliza Sydney. Right: Ellen Vernon tells Katherine Wilmot. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Isabella Alteroni

In chapter 38, “The Visit,” Reynolds takes Richard Markham, who has recently been released from prison after having served two years for a forgery he did not commit, into the world of a wealthy Italian nobleman in exile. “Armstrong, the political martyr with whom he had become acquainted in Newgate,” arrives to take him to visit Count Alteroni, explaining that he had met his Italian friend “at Montoni, the capital of the Grand Duchy of Castelcicala . . . ; and his extremely liberal political opinions, which completely coincide with my own, were the foundation of a staunch friendship between us.” Armstrong takes Markham, still traumatized by his time in prison, to meet the Alteroni family as a way of easing him back into society. Count Alteroni, it turns out, has a beautiful daughter, Isablla, whom the narrator describes in one of the characteristic purple passages to which eh resorts when describing sexually attractive women:

To say that she was beautiful were to say nothing. Her aspect was resplendent with all those graces which innocence lavishly diffuses over the lineaments of loveliness. She was sixteen years old; and her dark black eyes were animated with all the fire of that impassioned age, when even the most rugged paths of life seem adorned and strewed with flowers. Her mouth was small; but the lips were full and pouting, and revealed, when she smiled, a set of beautifully white and even teeth. Her hair was dark as the raven's wing, and was invariably arranged in the most natural and simple manner. Her brows were exquisitely pencilled; and as her large black eyes were the mirror of her pure and guileless soul, when she glanced downwards, and those expressive orbs were concealed by their long black fringes, it seemed as if she were drawing a veil over her thoughts. Her complexion was that of a brunette; but the pure, red blood shone in her vermilion lips and her rose-tinted nostrils, and mantled her pure brow with a crimson hue when any passion was excited. Her sylph-like figure was modelled with the most perfect symmetry. Her waist was so delicate, and her hands and feet so small, that it was easy to perceive she came of patrician blood; and the swell of her bosom gave a proper roundness to her form, without expanding into proportions that might be termed voluptuous.

Having thus described her physical beauty, the narrator next explains that her English education has made her a perfect blend of the best of Britain and Italy:

In manners, disposition, and accomplishments Isabel was equally calculated to charm all her acquaintances. Having finished her education in England, she had united all the solid morality of English manners, with the sprightliness and vivacity of her native clime; and as she was without levity and frivolity, she was also entirely free from any insipid and ridiculous affectations. She was artlessness itself; her manners commanded universal respect; and her bearing alone repressed the impertinence of the libertine's gaze. With a disposition naturally lively, she was still attached to serious pursuits; and her mind was well stored with all useful information, and embellished with every feminine accomplishment.

We do not learn what the feminine accomplishments of this sixteen-year-old might be, but earlier in the novel when Reynolds introduces Mrs. Diana Arlington, the mistress of several of the main characters, it soon becomes obvious that ability to make use of her beauty for economic survival and even prosperity is one of them.

Diana Arlington

We first see this great beauty, who would have done well at the court of Louis XIV, through the eyes of Richard Markham, who thinks

The Honourable Mr. Arthur Chichester had not exaggerated his description of the beauty of the Enchantress — for so she was called by the male portion of her admirers. Indeed, she was of exquisite loveliness. Her dark-brown hair was arranged en bandeaux, and parted over a forehead polished as marble. Her eyes were large, and of that soft dark melting blue which seems to form a heaven of promises and bliss to gladden the beholder.

She was not above the middle height of woman; but her form was modelled to the most exquisite and voluptuous symmetry. Her figure reminded the spectator of the body of the wasp, so taper was the waist, and so exuberant was the swell of the bust.

Her mouth was small and pouting; but, when she smiled, the parting roses of the lips displayed a set of teeth white as the pearls of the East.

Her hand would have made the envy of a queen. And yet, above all these charms, a certain something which could not be exactly denominated boldness nor effrontery, but which was the very reverse of extreme reserve, immediately struck Richard Markham. [Ch. 6, Mrs. Arlington]

In chapter 25, “The Enchantress,” we read that Markham, having realized that Sir Rupert Harborough and Chichester are criminals, has his valet Wittingham bring her a letter warning Mrs. Arlington to take guard against them. When she breaks with Harborough, who has been keeping her as his mistress, he angrily exclaims, “the world is coming to a pretty pass when one's own mistress undertakes to give lessons in morality,” and tells her she can go to the workhouse. Realizing that she cannot go to the authorities who would never take her word against a member of the nobility — the novel has established this multiple times already — she looks to her own survival, going to her desk, where “from a secret drawer she took several letters — or rather notes — written upon paper of different colours. Upon the various envelopes were seals impressed with armorial bearings, some of which were surmounted by coronets.” These turn out to be offers from men of various ages and wealth who want her to be their mistress, and considering each author with the care and skill she would have used to hire a servant, she first tosses the proposal from the “detestably conceited” French Count de Lestranges into the fire, after which she rejects the offer from Lord Templeton who is “so old and ugly.” Next, a third proposal goes into the fir:

“Here is a beautiful specimen of calligraphy,” resumed Diana, taking up a third letter; “but all the sentiments are copied, word for word, out of the love-scenes in Anne Radcliffe's romances. Never was such gross plagiarism! He merits the punishment I thus inflict upon him;” — and her plump white hand crushed the epistle ere she threw it into the fire.

Next into the flames is a letter from a German baron filled with philosophizing about love, and his offer is followed by one from a Greek, Finally, she decides, “the Earl of Warrington has gained the prize. He is rich — unmarried — handsome — and still in the prime of life! There is no room for hesitation.” Diana, who gives important aid to some of the better characters in the novel, knows what to do with her beauty and charm, and Reynolds seems to approve!

Reynolds' notions of female beauty

So what, according to Reynolds, are the qualities that make up a woman's physical beauty? They turn out to be largely those qualities the Pre-Raphaelites, who followed Dante Gabriel Rossetti, rejected when they created (or followed) an ideal woman with strong necks and chins that allowed little room for tiny feet and hands. Here, in contrast, are the qualities to which Reynolds returns again and again:

- polished ivory whiteness of the plump fair flesh

- admirable slope of the shoulders

- swan-like neck

- exquisite symmetry of the bust, contours of her bust were modelled in that ample and voluptuous mould

- masses of luxuriant and shining hair.

- high and ample forehead

- a nose perfectly straight and delicately-chiselled

- large eyes

- long black fringes (eyelashes)

- pouting lips

- beautifully white and even teeth

- well rounded chin

- Her figure reminded the spectator of the body of the wasp, so taper[ed] was the waist, and so exuberant was the swell of the bust.

- graceful in her deportment

- charming in all her movements

- long narrow foot

Bibliography

Reynolds, George W. M. The Mysteries of London. vol 1. Project Gutenberg EBook #47312 produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team from images available at Google Books. Web. 2 August 2016.

Last modified 5 October 2016