For his second novel, based on the experiences of family friend Colonel John Mackay in the peninsular Campaign, Charles Lever was perhaps thinking of Captain Frederick Marryat's first best-seller, Frank Mildmay, or, The Naval Officer (1829). However, the new novel's target audience was certainly not Marryat's young readers. "Gleig's Subaltern [1825, from Blackwood's Magazine], Hamilton's Cyril Thornton [1827], and Maxwell's two or three books lacked sustained literary power to win lasting fame" (Stevenson, 76), but may have furnished further models of pseudo-biographies emphasizing what Lever termed "The soldier element." The other principal characters also have their origins in Dubliners whom Lever knew well: Richard Martin, M. P., is the model for Godfrey O'Malley; Sir Harry Boyle is based on Sir Boyle Roche; the dashing female lead, Baby Blake, is a Miss French of Moneyvoe, Castle Blakeney; and, most significantly, the comic servant Mickey Free "was a composite of several droll grooms and valets Lever had known" (Stevenson, 77).

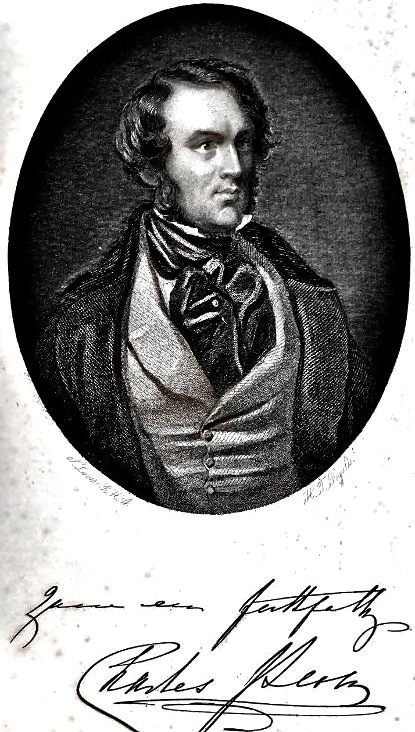

Once again Lever employed Hablot Knight Browne as his illustrator as he had for the military retrospective The Confessions of Harry Lorrequer (February 1837 through February 1840, intermittently). Like his first novel, Lever's second initially appeared serially in monthly numbers of The Dublin University Magazine (founded in 1833; dissolved in 1882). The novel also appeared in two volumes December 1840, a year ahead of the end of the serial run of twenty-two monthly instalments. Although the Peninsular campaigns of the Napoleonic Wars were long past, Lever imbued his account of them with energy and humour, still working in the caricatural vein of picaresque novels of the period. He followed this comic war novel with two more of the same type, Jack Hinton, The Guardsman (1843) and Tom Burke of Ours (1844). Lever during this period signed himself as "Harry Lorrequer," the pen-name he adopted for the genial first-person narrator of his first two novels. On the strength of a diplomatic connection, Lever established himself as a physician to high society in Brussels before the volume edition of Harry Lorrequer appeared in late 1839.

Lever moved much of the action in his second novel, Charles O'Malley, the Irish Dragoon (1841) to the Continent at the time of the Peninsular War and the Battle of Waterloo, drawing on what he calls 'the inexhaustible store of fun and buoyancy within me'. Indeed, Lever is at his funniest in this book, and the public was particularly captivated by Lever's answer to Dickens's Sam Weller, the irrepressible Mickey Free, complete with striped waistcoat. . . . Phiz was completely at home rendering a Sam-like Mickey; but other images in this novel are thin and hurried (not surprising with Little Nell breathing down his neck). Lever invited him to Brussels for this reason, suggesting he travel there with Samuel Lover, who was going to paint his portrait. While Lover worked, Lever could describe to Phiz the gang of wild characters springing to mind for his next novel, Jack Hinton. [Lester, 114-115]

The Belgian trip stretched out beyond two weeks, so well did the two artists and the novelist amuse one another with daily dinners on a grand scale and Lever's lengthy anecdotes: the trio instituted a pseudo aristocratic order they dubbed "Knights Grand Cross, with music, procession, and a grand ballet to conclude. They did nothing all day, or, in some instances, all night, but eat, drink, and laugh. During the sixteen days of the visit they consumed nine dozen of champagne" (Stevenson, 95). The whole interlude was like a scene out of one of Lever's novels.

Although a good deal jollier and anecdotal than Dickens, Lever was not nearly as prompt with providing monthly copy. He often left Phiz scrambling, especially since over their period of collaboration on Charles O'Malley in 1840-41 Phiz had eleven other commissions, including three from the demanding Boz: Sketches of Young Couples, Master Humphrey's Clock, and The Pic-nic Papers. Indeed, Lever worried that Phiz was making his O'Malley and Hinton engravings look too much like his illustrations for Pickwick and Nickleby because Phiz relied during his caricatural period on stereotypes. No wonder the Belgian King (to whom Lever was presented in British military uniform at the time) laughed uproariously at something he had read in O'Malley. However, the publishing of the novel was not without its complications, as when, for example, a fire at Folds' (the publisher) printing-office resulted in the loss of the ms. for the next instalment. Since Lever was not in the habit of retaining an extra copy, he "was particularly anxious lest Phiz had drawn his illustrations for some scenes which the author would be unable to recollect" (Stevenson, 85).

The following list of chapter instalments is based on volumes 15 through 18 of the Dublin University Magazine, of which Lever was the editor. However, in O'Malley, he presents himself in the persona of Harry Lorrequer. Only the separate monthly numbers published by William Curry carried the Phiz illustrations. * To capitalise on the Christmas book sales, Curry issued Parts 21 and 22 simultaneously as a single "double-number" in November 1841.

The Novel's Twenty-two Serial Instalments (March 1840-December* 1841)

- 1 March 1840 "Introduction" (Brussels, February 1840) plus Chapters I-III.

- 2. April 1840 Chapters IV-VI.

- 3. May 1840 Chapters VII-XII.

- 4. June 1840 Chapters XIII-XVII.

- 5. July 1840 Chapters XVIII-XXII.

- 6. August 1840 Chapters XXIII-XXIX.

- 7. September 1840 Chapters XXX-XXXIV.

- 8. October 1840 Chapters XXXV-XLI.

- 9. November 1840 Chapters XLII-XLVII.

- 10. December 1840 Chapters XLVIII-LV.

- 11. January 1841 Chapters LVI-LXIV.

- 12. February 1841 Chapters LXV-LXVII.

- 13. March 1841 Chapters LXVIII-LXXIII.

- 14. April 1841 Chapters LXXIV-LXXIX.

- 15. May 1841 Chapters LXXX-LXXXV.

- 16. June 1841 Chapters LXXXVI-XC.

- 17. July 1841 Chapters XCI-XCV.

- 18. August 1841 Chapters XCVI-CII.

- 19. September 1841 Chapters CIII-CVIII.

- 20. October 1841 Chapters CIX-CXIII.

- 21. November 1841 Chapters CXIV-CXVII.*

- 22. December 1841 Chapters CXVIII. — Conclusion. L'Envoi.

Our Mess.

Meanwhile, believe me most respectfully and faithfully yours,

Harry Lorrequer.

Brussels, November, 1841. [Dublin University Magazine, 678] The same notice as "A Word of Explanation" by Harry Lorrequer is dated Brussels, March 1840.

Discussions

- The Comic Characters in Charles O’Malley: Frank Webber, Major Monsoon, and the Indefatigable Mickey Free

- Charles Lever's Winning Formula and the Conclusion of Charles O'Malley

Bibliography

Buchanan-Brown, John. Phiz! Illustrator of Dickens' World. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1978.

Lester, Valerie Browne Lester. Chapter 11: "'Give Me Back the Freshness of the Morning!'" Phiz! The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004. Pp. 108-127.

Lever, Charles. The Martins of Cro' Martin. With illustrations by Phiz. 2 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1856, rpt. London & New York: Routledge, 1873.

Lever, Charles. The Martins of Cro' Martin. Illustrated by Phiz [Hablot Knight Browne]. Novels and Romances of Charles Lever. Introduction by Andrew Lang. Lorrequer Edition. Vols. XII and XIII. In two volumes. Boston: Little, Brown, 1907.

Steig, Michael. Chapter Two: "The Beginnings of 'Phiz': Pickwick, Nickleby, and the Emergence from Caricature." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington and London: Indiana U. P., 1978. Pp. 24-50.

Stevenson, Lionel. Dr. Quicksilver: The Life of Charles Lever. New York: Russell & Russell, 1939, rpt. 1969.

Created 16 February 2023