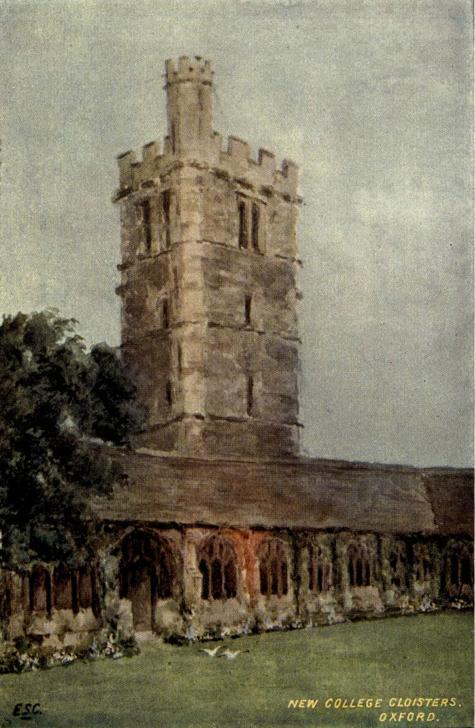

Left to right: (a) View from Cloisters, by Mathieson. (b) The Cloisters of New College Chapel, by "E.S.C." (c) The Chapel: East End from a photograph by the Oxford Camera Club. Source: Rashdall and Rait, facing p. 130. [Click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information about the first two.]

Holy Thursday, 25 May [1876]

This afternoon Mayhew and I attended the evensong of the Ascension at New College Chapel. Before the service began, finding the cloister gate open, we strolled round the grey peaceful green cloisters where high overhead the two great bells were chiming sweetly and deeply for evensong in the tall old turreted grey tower. There is something about the cloisters of New College which is more grey and hoary and venerable than anything about the cloisters of Magdalen. They have an air of higher antiquity and a more severely monastic look. Indeed one half expects still to meet grey monkish figures still pacing round the stone-flagged cloisters or crossing the square open greensward in the centre and looking up and listening to the bells chiming overhead in the great grey Tower.

The Chapel was filled with people. There were 'High Prayers', a magnificent tempest of an Anthem, and a superb voluntary after the service during which people stood about in picturesque groups in the light streaming from the great West window or sat listening in the Antechapel stalls.

Father Arthur Henry Stanton (1839-1913), by Samuel Alexander Walker, an albumen carte-de-visite of the 1860s, courtesy of the Nation Portrait Gallery, London. NPG x8352. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

We went to hear Father Stanton preach at St. Barnabas. The service was at 8 o'clock and the evening light was setting behind the lofty Campanile as we entered. The large Church was almost full, the great congregation singing like one man. The clergy [338/339] and choir entered with a procession, incense bearers and a great gilt cross, the thurifers and acolytes being in short white surplices over scarlet cassocks and the last priest in the procession wearing a biretta and a chasuble stiff with gold. The Magnificat seemed to be the central point in the service and at the words "For behold from henceforth all generations shall call me blessed" the black biretta and golden chasuble (named Shuttleworth) advanced, was "censed" by the thurifer, then took the censer from him and censed the cross, the banners, the lights and the altar, till the Church was all in a fume. At least so Mayhew said. I myself could not see exactly what was done though I knew some ceremony was going on. It appeared to me to be pure Mariolatry. Father Stanton took for his text "He is altogether lovely," Canticles ii. The matter was not original or interesting, and the manner was theatrical and overdone. I should think every eye in that great congregation was quite dry. The text was repeated constantly in a very low die-away tone. The sermon came after the Third Collect. I was disappointed in it and so I think were many more. After the service there was an offertory and a processional hymn, and then round came the procession down the South aisle and up the nave in the following order. First the thurifer in short white surplice and scarlet cassock swinging a chained censer high in the air and bringing it back with a sudden check and violent jerk which brought the incense out in stifling cloud. Next an acolyte in a similar dress bearing aloft a great gilt cross. Then three banners waving and moving above the heads of the people in a weird strange ghostly march, as the banner-bearers steered them clear of the gaslights. After them came two wand- bearers preceding the clergy, Father Stanton walking in the midst and looking exhausted, the rear of the procession being brought up by the hideous figure of the emaciated ghost in the black biretta and golden chasuble.

As we came out of Church Mayhew said to me, "Well, did you ever see such a function as that?" No, I never did and I don't care if I never do again. This was the grand function of the Ascension at St. Barnabas, Oxford. The poor humble Roman Church hard by is quite plain, simple and Low Church in its ritual compared with St. Barnabas in its festal dress on high days and holidays. [338-39]

Commentary

On Monday 22 May 1876, the Reverend Kilvert had gone to visit his "dear old College friend" from Wadham, Anthony Lawson Mayhew (331). Not having been to Oxford for two years, he was overcome with "an indescribable thrill of pride and love and enthusiasm" as he saw the University buildings from the train, and thoroughly enjoyed his stay there (331). On the Thursday, they took part in the customs of Ascension Day. Too late for the morning service at Magdalen, they went to the one at Merton, sitting in the stalls of the Ante Chapel there. Then they wandered along Terrace Walk, witnessing the traditional ceremony of the beating of the bounds, being regaled like the rest of the participants with bread, cheese and ale at Corpus Christi College. Later they went to Evensong at New College Chapel, and finally, in the evening, they went to hear Father Stanton (1839-1913) preach at St Barnabas, an Italianate church with a tall campanile near the Oxford Canal.

Stanton himself was visiting from St Alban the Martyr in Holborn, where he was the long-time curate, well known (and often censured) for his persistent and extreme Anglo-Catholicism. Roger T. Stearn writes, "Stanton was tall and handsome, and his black hair and olive skin gave him a foreign appearance. A celibate, habitually wearing cassock and biretta, and known as Father Stanton, he was enthusiastic for 'the sweet incense and the gorgeous vestments.'" Unpretentious himself, the Reverend Kilvert evidently found the service too high and showy for him, and would have preferred a simpler one in the "humble" albeit actually Roman Catholic church nearby.

This account gives a useful insight into the sort of divisions that existed in religious life during the mid- to late-Victorian period, when Anglo-Catholicism could actually outdo Roman Catholicism in its emphasis on ritual and ceremony. As a High Churchman of the old school himself, Kilvert was wary of it. But, as David King has noted, he did not involve himself in the complex issues that troubled some churchmen. Although ritualism was clearly not to his taste, as the ending of this passage indicates, he was not bitterly against Roman Catholicism either. Rather, King suggests, he reflected "the sentimentalism of much Mid-Victorian religion," and focused on his calling "to uplift the young, the poor, and the bereaved to whom he ministered" (74). There could hardly have been a better attitude for a country pastor, and it is not surprising that Kilvert won the hearts of his parishioners. — Jacqueline Banerjee

Bibliography

Kilvert’s Diary (a selection). Ed. William Plomer. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1977.

King, David R. "Francis Kilvert: The Faith of a Rural, Victorian Pastor." Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church 50/1 (March 1981): 73-82. Available on Jstor.

[Illustration source] Rashdall, Hastings, and Robert S. Rait. New College. London: F. E. Robinson, 1901. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California Libraries. Web. 10 April 2020.

Stearn, Roger T. "Stanton, Arthur Henry (1839–1913), Church of England clergyman." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. 10 April 2020.

Created 10 April 2020